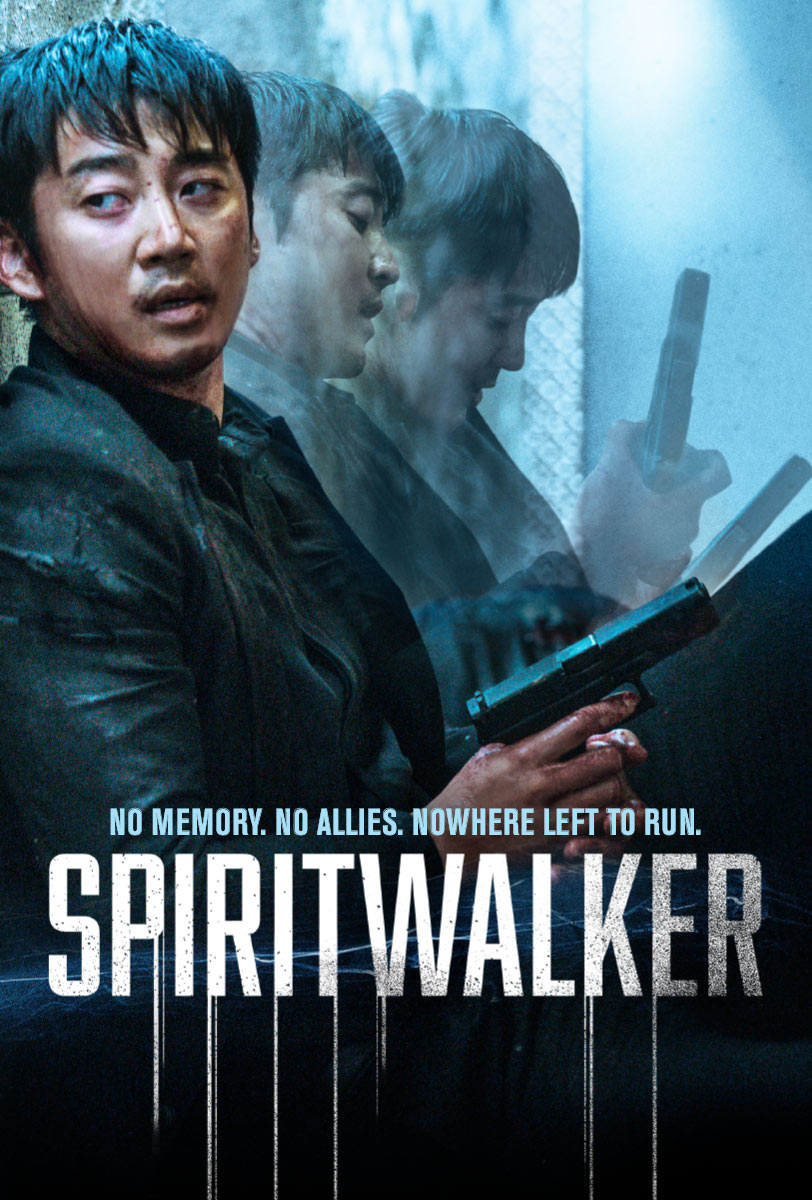

“Who do you think I am?” the amnesiac hero of Yoon Jae-geun’s existential thriller Spiritwalker (유체이탈자, Yucheitalja) eventually asks having gained the key to his identity but continuing to look for it in the eyes of others. Yet as he’s told by an unlikely spirit guide, maybe knowing who you are isn’t as important as knowing where you’ve come from and where it is you’re going advising him to retrace his steps in order to piece his fragmented sense of self back together.

A man (Yoon Kye-sang) comes round after a car accident with no memory of who he is or how he got there. He arrives at the hospital after a homeless man (Park Ji-hwan) calls an ambulance for him, but quickly realises he might be in some kind of trouble especially as the police are keen to find out who shot him and why. With that in mind, he decides to make a break for it but finds his sense of reality distorted once again as the world around him changes eventually realising that he’s shifted into the body of another man somehow connected to his “disappearance”. In fact this happens to him every 12 hours which is in many ways inconvenient as his impermanence hampers his ability to keep hold of the evidence he’s gathered while preventing him from making allies save for the homeless man who is the only one to believe his body-hopping story.

As the homeless man points out, no-one in his camp really knows who they are anymore and to a certain extent it doesn’t really matter (in fact, he never gives his own name) because they have already become lost to their society as displaced as the hero if in a slightly different way forever denied an identity. What the homeless man teaches him, however, is that the essence of his soul has remained figuring out that at the very least he’s a guy who prefers hotdogs to croquettes even if he can’t remember why which is as good a place to found a self on as anywhere else. Even so, through his body-hopping journey he begins to notice that all of his hosts are in someway linked, inhabiting the same world and each possessing clues to the nature of his true identity.

The central mystery, meanwhile, revolves around a high tech street drug originating in Thailand which causes hallucinations and a separation of body and soul apparently trafficked to Korea via a flamboyant Japanese gangster with the assistance of the Russian mafia in league with corrupt law enforcement members of which have begun getting dangerously high on their own supply with terrible if predictable results. This sense of uncertainty, that everyone is operating under a cover identity and those we assumed to be “good” might actually be “bad” and vice versa leans in to Yoon’s key themes in which nothing is really as it seems. Body and soul no longer align, the hero constantly surprised on catching sight of “himself” in mirrors, not knowing his own face but realising that this isn’t it while desperate for someone to “recognise” him as distinct from the corporeal form he currently inhabits. Though they may not be able to identify him, some are able to detect that he isn’t “himself”, behaving differently than expected, speaking in a different register, or moving in a way that is uniquely his own even while affected by other physical limitations such as one host’s persistent limp.

Inevitably, the hero’s path back to reclaiming his identity lies in unlocking the conspiracy of which he finds himself at the centre, figuring out which side he’s on and what his highest priorities are or should be in gaining a clear picture of his true self as distinct from the self that others see. High impact hand-to-hand combat sequences give way to firefights and car chases while the hero finds himself constantly on the run in an ever shifting reality, Yoon employing some nifty effects as an apartment suddenly morphs into a coffee shop as the hero shifts from one life to another existentially discombobulated by the lives of others but always on the search for himself and a path back to before finding it only in the returned gaze of true recognition.

Spiritwalker is released on blu-ray in the US April 12 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Interntational trailer (English subtitles)