“You have my full support. Do as you please” so says the dictator, unambiguously manipulative but still somehow inspiring the loyalty of his many underlings perhaps still too wedded to an idea or at least an ideology to countenance moving against him. It turns out that nothing really changes and whether it’s feudal Joseon or the modern nation state, there is intrigue in the court. Neatly adopting the trappings of a ‘70s conspiracy thriller, Woo Min-ho’s The Man Standing Next (남산의 부장들, Namsanui Bujangdeul) explores the events which led to the assassination of President Park Chung-hee, father of the recently deposed president Park Geun-hye, by a member of his own security team. Many of the names have been changed and historical liberties taken, but the lesson seems to be that there is always a man standing next in readiness to inherit the throne.

Our hero is KCIA chief Kim Gyu-peong (Lee Byung-hun), preparing as the film opens to halt Park’s (Lee Sung-min) increasing authoritarianism by assassinating him. A combination of the personal and the political Gyu-peong’s eventual epiphany is precipitated by an old friend’s “defection”. Park Yong-gak (Kwak Do-won), former director of the KCIA which operated as a secret police force propping up Park Chung-hee’s oppressive regime, is giving testimony to an American inquiry into the so-called “Koreagate” scandal in which the KCIA is accused of bribing members of Congress to propagate favourable views of the Korean president and reverse Nixon’s decision to pull US troops from South Korea. Yong-gak uses the opportunity to denounce Park Chung-hee, planning to publish a memoir titled “Traitor of the Revolution” as an exposé of the inner workings of the KCIA.

Somewhat ironically, Gye-peong and Yong-gak are old comrades who fought together in the “revolution” led by Park in the early 1960s following the ousting of corrupt autocrat Rhee Syngman. Yong-gak has become disillusioned with their cause and with Park himself, but this largely ignores the fact that Park’s revolution was mainly a repackaging of Japanese militarism, something signalled by an exchanged between Park and Gye-pyeong in Japanese to the effect that their days of revolution were their best. All of which makes Yong-gak’s wistful eulogising of a betrayed ideal along with his supposed admiration for democracy somewhat ironic. The essential motivator in their loss of faith, however, is also a militaristic one. They learn firstly that like any dictator Park has been embezzling from the state for years and has a collection of slush funds in Switzerland. That’s not the problem, the problem is that to manage them he’s been running a “private” intelligence service unknown even to the KCIA. They’ve been displaced, and their hurt is personal more than it is political.

Yong-gak calls Park a traitor to their revolution and objects to the continuing human rights abuses for which he himself as a member of the KCIA has been directly responsible. All of this creates a series of crises for Gye-peong who is torn between loyalty to his old friend and Park while increasingly worried for his own safety. He begins to suspect that Gwak (Lee Hee-joon), Park’s security officer who had not fought with them in the revolution, may be the mysterious “Iago” figure Yong-gak had been warned about by the CIA. Increasingly sidelined, Gye-peong continues to do Park’s dirty work but draws attention to himself in his resistance towards the president’s increasingly militaristic rhetoric. Pro-democracy protests have already broken out in Busan in response to Park’s “unfair” treatment of the city’s governor and the opposition party. Gye-peong advises reinstating the governor with an apology. Gwak says frame the protestors as communists and Northern sympathisers and send in the tanks. “Cambodia killed three million people, is it such a big deal if we kill one or two million?” Gwak blurts out in a quip which seems to catch Park’s attention, the president now thinking himself untouchable. A militarist perhaps but an educated man who speaks good English and gets on well with the Americans, Gye-peong does not see the Khmer Rouge as a source of inspiration nor, like Yong-gak, does he think those values align with the ones he fought for bringing Park to power.

Then again, even in the immediate chaos of the early ‘60s, it’s difficult to see how you could join that particular revolution without assuming it would come to this. Gye-peong has apparently been OK with human rights abuses and mass oppression, but has been quietly reassuring himself and others that Korea is changing, Park is preparing to move aside, and they are progressing towards democracy. In true conspiracy fashion, Woo paints Gye-peong as a tragic hero, unable to reconcile himself with the choices he has made or the radically different version of the world he is now seeing, but taking what is essentially a personal revenge in return for a slighting from a man to whom he’d given his life. Perhaps in a sense he thinks he’s saving Park from himself, or merely protecting the revolution he fought for from a cruel traitor, but in the end lacks the courage to carry it through. He thought Gwak was his Iago, but he missed the “man standing next” in the shadows. As the April Revolution led only to Park, so Park leads only to Chun and second military coup even more brutal than the last. Nothing really changes, but the next revolution will have to be one enacted by more peaceful means because the spectre of authoritarianism is eclipsed only in the freedom from fear.

The Man Standing Next is available to stream in the UK from June 25 and on download July 5 courtesy of Blue Finch Releasing.

International trailer (English subtitles)

You gotta know how to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away and know when to run. Apparently these rules of the table are just as important in the cutthroat world of the Korean card game Hwatu as they are in the rootinest tootinest saloon bar. Like most card games, having the winning hand is less important than the ability to play your opponent and so it’s more a question of who can cheat the best (without actually breaking the rules, or at least being caught doing so) than it is of skill or luck. A second generation sequel to 2006’s Tazza: The High Rollers, The Hidden Card (타짜-신의 손, Tajja: Shinui Son) is a slick, if overlong, journey into the dark, underground world of gambling addicted card players which turns out to be much more shady than the shiny suits and cheesy grins would suggest.

You gotta know how to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away and know when to run. Apparently these rules of the table are just as important in the cutthroat world of the Korean card game Hwatu as they are in the rootinest tootinest saloon bar. Like most card games, having the winning hand is less important than the ability to play your opponent and so it’s more a question of who can cheat the best (without actually breaking the rules, or at least being caught doing so) than it is of skill or luck. A second generation sequel to 2006’s Tazza: The High Rollers, The Hidden Card (타짜-신의 손, Tajja: Shinui Son) is a slick, if overlong, journey into the dark, underground world of gambling addicted card players which turns out to be much more shady than the shiny suits and cheesy grins would suggest.

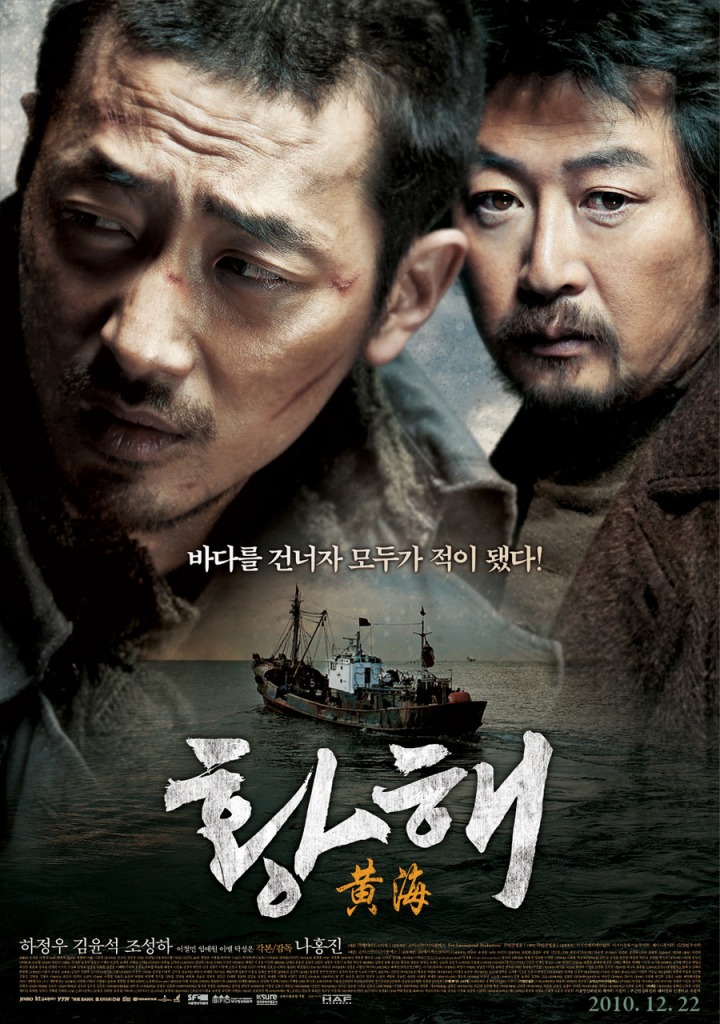

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand – the residents of Goksung, the setting for Na Hong-jin’s nihilistic horror movie The Wailing (곡성, Goksung), might be inclined to agree with Yeats if only because the name of their town is also a homonym for the “sound of weeping”. There is plenty to weep over, and in places Na’s film begins to feel like one long plaintive cry reaching far back to the dawn of time but the main wounds are comparatively more recent – colonisation, not only of a landscape but of a soul. When it comes to gods, should you trust one over another simply because of its country of origin or is your faith to be bestowed in something with more universal application?

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand – the residents of Goksung, the setting for Na Hong-jin’s nihilistic horror movie The Wailing (곡성, Goksung), might be inclined to agree with Yeats if only because the name of their town is also a homonym for the “sound of weeping”. There is plenty to weep over, and in places Na’s film begins to feel like one long plaintive cry reaching far back to the dawn of time but the main wounds are comparatively more recent – colonisation, not only of a landscape but of a soul. When it comes to gods, should you trust one over another simply because of its country of origin or is your faith to be bestowed in something with more universal application?