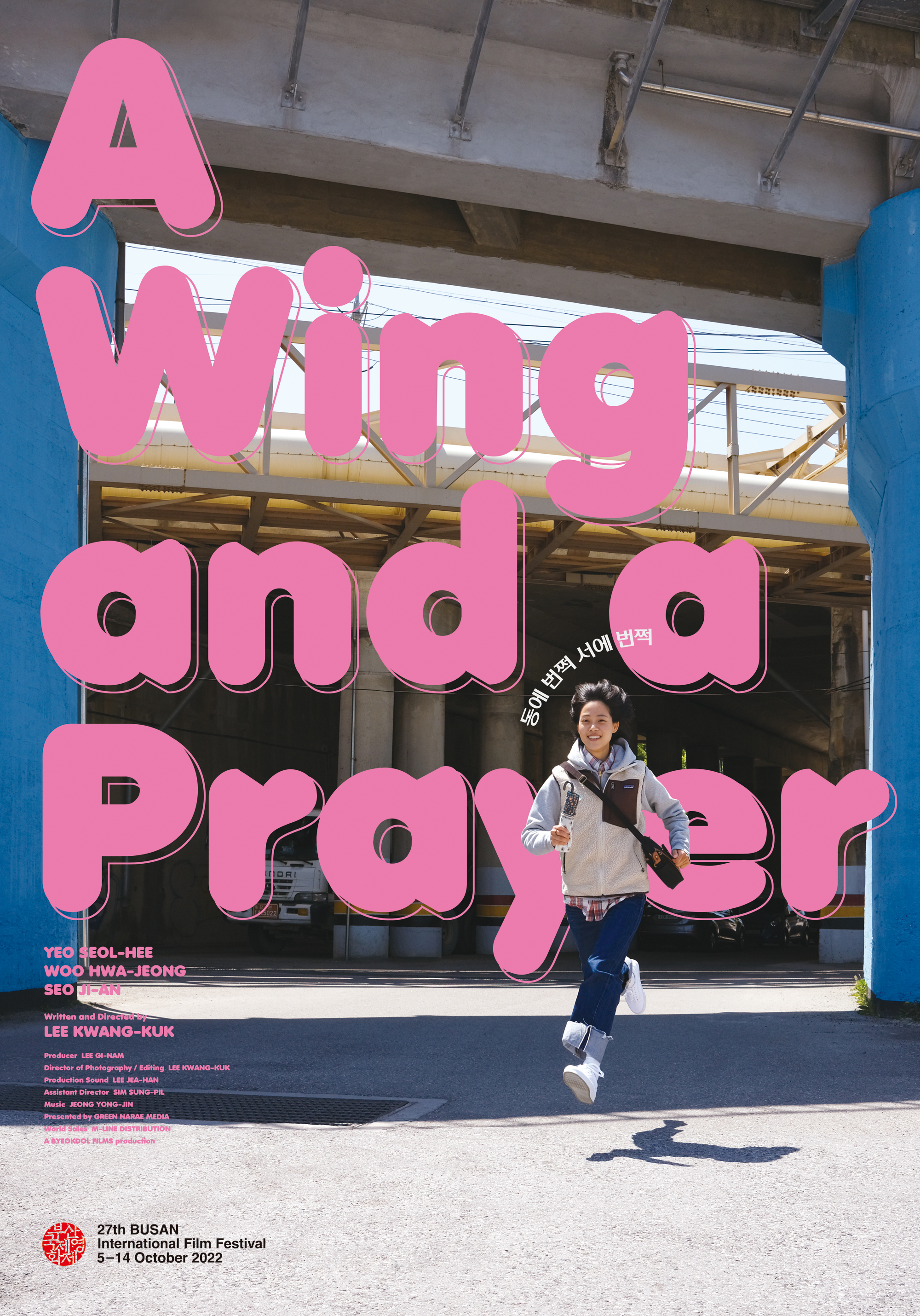

A pair of 25 year olds find themselves marooned in adolescence thanks to the precarious socio-economic conditions of contemporary Korea in Lee Kwang-kuk’s indie dramedy A Wing and a Prayer (동에 번쩍 서에 번쩍, Dong-e Beonjjeog Seo-e Beonjjeog). Not quite as quirky as Lee’s previous work, the film nevertheless finds its twin protagonists undergoing parallel journeys while each preoccupied with the progression to adulthood and what that might actually mean in real terms while perhaps guilty of a childish naivety in their vision of what it is to be grown up.

Seol-hee (Yeo Seo-hee) and Hwa-jeong (Woo Hwa-jeong) are best friends and roommates each currently without jobs and feeling lost without clear direction for their future. Seol-hee was on track to be an athlete but was forced to give up following injury. At an interview for a job in a coffee shop she’s asked a series of questions which seem to her somewhat unnecessary. “Do I need a dream in order to work here?” she asks, “Can’t I just make good coffee and try my best at everything?” Predictably, her answer does not go down well with the interviewer and it seems unlikely she’s going to get this job though Seol-hee remains cheerful and upbeat unable to understand why everyone keeps pressing her about her hopes and dreams when she’s just trying to live. By contrast, Hwa-jeong has reached the final stages for a job at a company and feels her interview went well so she’s optimistic that this time it really might work out.

Though in quite different places, the pair decide to take an impromptu trip to the seaside to wish on the sunrise only to fall asleep and completely miss the moment. The mismatch in their circumstances comes to the fore when Hwa-jeong reveals that with their lease about to come to an end she’d like to try living on her own, “like a real adult”. Of course, that’s quite destabilising and hurtful for Seol-hee who has no real expectation of being able to get the kind of job that would let her find an apartment she could rent on her own. After a small argument, the pair end up separated and on parallel adventures as Seol-hee bonds with a slightly older woman, Ji-an (Seo Ji-an), whose life has been ruined by unresolved trauma caused by high school bullying while Hwang-jeong meets a high schooler, also bullied, who is looking for her missing parrot.

When Hwang-jeong comes to the rescue of the high school girl after she’s lured by bullies who claimed to have info on her parrot, it’s obvious that they immediately recognise her as an “adult” though she holds little sway over them. Hwang-jeong is fond of saying that she isn’t a kid anymore, but it’s also clear that getting a job is central to her definition of adulthood. When the high school girl asks what she does for a living, Hwang-jeong answers pre-emptively that she’s a “respectable company employee” to which the high school girl replies “an adult” but then goes on to ask at exactly what age one becomes one. Hwang-jeong has no answer, because perhaps it’s not an age after all but a state of being.

She also accuses Seol-hee of behaving like a child as they continue to argue about Hwang-jeong’s plans for solo adulting. Seol-hee meanwhile finds herself trying to help another lost woman who is herself arrested but trying to break of the “jail” she feels she’s been placed in by an overprotective mother she nevertheless feels may be ashamed of her for her own “failure” to progress into a more conventional adulthood. Like the high school girl Seol-hee claims she has no friends and tries to make one of Ji-an only she refuses. On seeing the flyers for the lost parrot, which Seol-hee herself at times resembles, she wonders if recapturing it is the right thing to do or if it wouldn’t be happier flying free rather than trapped within a cage that to Seol-hee represents conventionality and socially accepted ideals of success.

They’re all lonely, wounded, and insecure, afraid of talking to each other about their worries because of the internalised shame of feeling to meet the demands of “adulthood” despite, in all but the case of the high school girl, being well over the age of majority. The high school girl herself may represent Hwang-jeong’s refusal to confront her past while throwing herself into an adulthood she hasn’t quite earned just as the parrot represents both her friendship with Seol-hee and the elusiveness of their future, but it also returns to her the sense of positivity she may have been missing just as Seol-hee’s care of Ji-an also allows her to take care of herself. They might not quite be adults, but then who really is and at least they have a little more clarity about that means and what they want out of life in the realisation that they aren’t alone and not least in their worries.

A Wing and a Prayer screens 10th November as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)