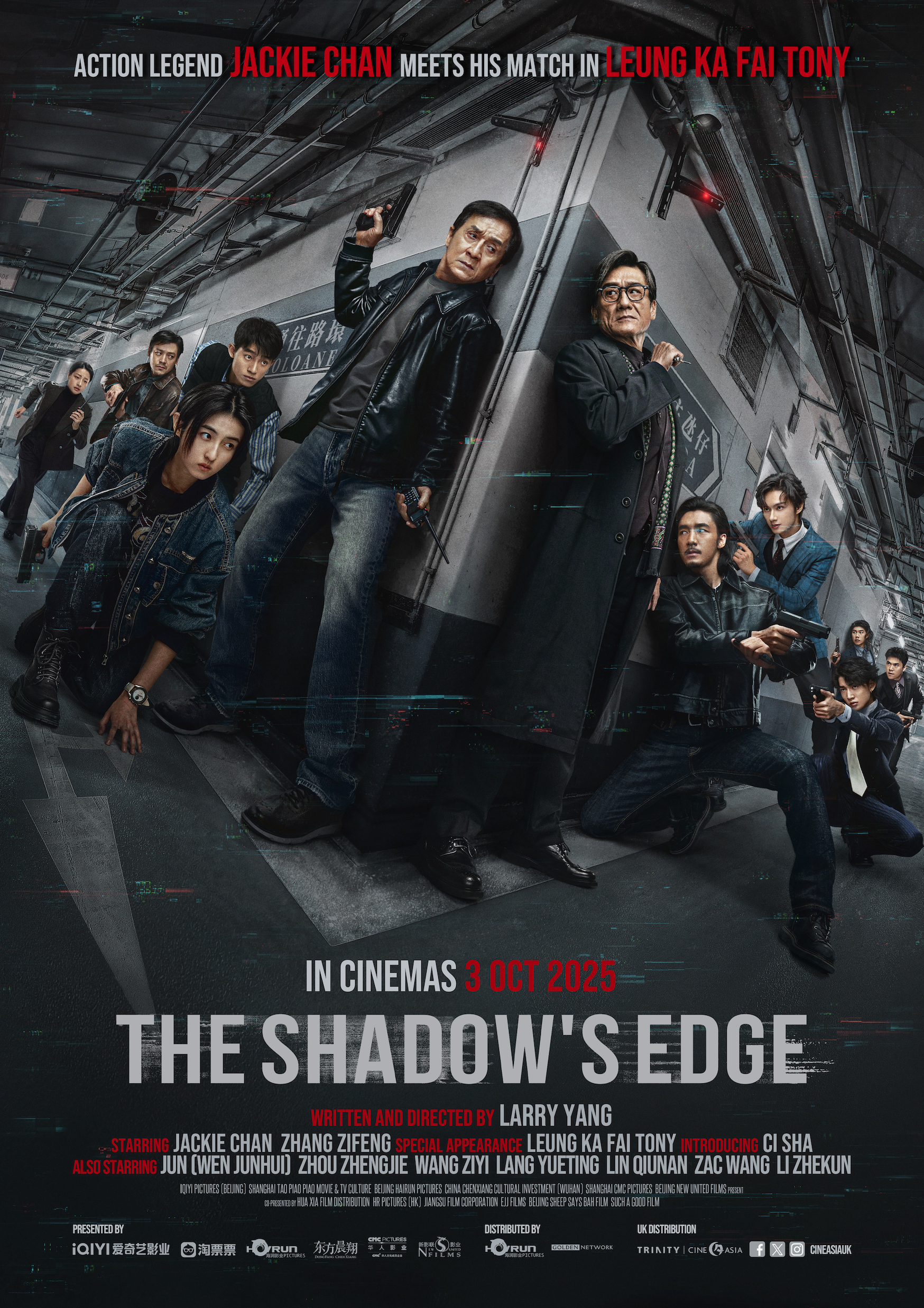

China’s mass surveillance system has come to the rescue in many a recent action film, as if it were saying that China will always find you if you’re in trouble but perhaps also if you’re the one making it. A loose Mandarin-language remake of 2007’s Eye in the Sky, The Shadow’s Edge (捕风追影, Bǔfēng zhuīyǐng) takes a slightly different tack in being somewhat wary of AI-based technology and the way it’s already embedded itself so deeply in our lives as to have engendered a rapid deskilling of the younger generation.

The Macau police force rarely conducts on the ground surveillance anymore and is heavily reliant on its network of video cameras along with facial recognition software. Madame Wang (Lang Yueting), however, the officer in charge ends up disabling the AI system because it’s proving unhelpful and undermining her authority. In any case, it leaves them vulnerable to interference and unbeknownst to them they’ve been hacked. A talented group of thieves have managed to throw them off the scent by manipulating the footage so it looks like their vehicle is in a completely different place while they’re busy committing the crime. The hackers have managed to combine new technologies and old in a much more successful way than the police as they use a mixture of traditional disguise techniques and well-honed spycraft along with video manipulation to evade detection.

It’s at this point that the police decide they need to bring back someone who still remembers how to do analogue police work to teach them how to combat this new digital threat. The irony is that the hackers are also being led by a veteran espionage expert now in his 70s and known only as “The Shadow” (Tony Leung Ka-fai). Though it’s true enough that he knows the evil that lurks in the hearts of men, The Shadow has surrounded himself with a group of former orphans whom he has trained in the arts of surveillance and infiltration while they take care of all the new technological stuff. But it’s also a slight degree of hubris and a mishandling of the digital side that leads to a slip-up in which the Shadow’s face may have been captured on camera for the first time in decades. As he ages out, there is conflict between father and sons as the boys begin to resent the Shadow’s paranoia and over cautiousness, wondering why they don’t simply take the bigger prize without considering that it may be more difficult to claim and leave them vulnerable to retribution.

Wong (Jackie Chan), the former special forces veteran officer they bring in to train the youngsters experiences something similar in the awkwardness of his relationship with Guoguo (Zhang Zifeng), the daughter of his former partner who was killed on the job because of an error in judgement made by Wong. Guoguo has been consistently sidelined by the police team where she’s surrounded by incredibly sexist men who doubt her ability to do the job because of her gender and short stature, and now has conflicting feelings about Wong that are bound up with her father’s death and a fear of being patronised convinced that Wong too is reluctant to let her do her job out of a problematic sense of overprotection.

Nevertheless, she proves a natural at the old-fashioned art of surveillance and develops a more positive kind of paternal relationship with Wong than that the Shadow has with his band of orphans. In essence, Guoguo learns both how to be part of a team and how to lead it, while Shadow’s boys don’t really learn much of anything beyond ruthlessness and generational conflict. In any case, the answer seems to be that’s what’s needed is both old and new, and that an over-reliance on technology isn’t helpful while AI isn’t necessarily faster than a finely tuned mind like the Shadow’s or merely someone who knows the backstreets well enough to anticipate an exit route. Drawing impressive performances from both his veteran leads, Yang succeeds in blending expertly crafted action sequences with interpersonal drama and giving the film a slick retro feel through the use of split screens and impressive editing. A post-credits sequence also hints at a wider conspiracy in play and the potential of a sequel, which would certainly be a welcome development given the strength and ambition of this opening instalment.

The Shadow’s Edge is in UK cinemas from 3rd October courtesy of CineAsia.

UK trailer (English subtitles)