Love – is it an act of fate or of free will? For the women of 18th century Korea, romance is a girlish affectation which must be outgrown in order to fulfil one’s proper obligations to a new family and the old by becoming the ideal wife to a man not of one’s own choosing. Love, in this world, would be more than an inconvenience. It would be a threat to the social order. In Hong Chang-pyo’s The Princess and the Matchmaker (궁합, Gunghab), each and every decision is dictated by birth, but as our soothsayer reminds us, serendipitous meetings can change all that’s gone before.

Love – is it an act of fate or of free will? For the women of 18th century Korea, romance is a girlish affectation which must be outgrown in order to fulfil one’s proper obligations to a new family and the old by becoming the ideal wife to a man not of one’s own choosing. Love, in this world, would be more than an inconvenience. It would be a threat to the social order. In Hong Chang-pyo’s The Princess and the Matchmaker (궁합, Gunghab), each and every decision is dictated by birth, but as our soothsayer reminds us, serendipitous meetings can change all that’s gone before.

A severe drought is plaguing the subjects of Joseon, and their eyes are on their king to sort it out. For complicated reasons, many assume the pause in the rains is down to the gods’ wrath over the aborted wedding of problematic princess Songhwa (Shim Eun-kyung) some three years previously. Even before her failed marriage made her a flawed woman, Songhwa had always been tainted with an aura of ill fortune seeing as her mother died in childbirth. A reading of her astrological charts implied her presence was bad for the king (Kim Sang-kyung) and so she was sent away only to be called back when another reading revealed her presence may be essential to the king’s recovery from illness. She’s been at the court ever since but the taboo of her supposed bad luck has never left her. The king determines he’ll have to marry Songhwa off to improve the public mood but with her reputation who will they be able to find for a husband? With names thin on the ground, the king decides on a series of open auditions with the royal astrologer announcing the “winner” after a thorough examination of their birth charts.

It goes without saying that no one is especially interested in Songhwa’s opinion. Still naive and innocent, Songhwa is quite looking forward to finally getting married though a frank conversation with a recently hitched friend perhaps helps to lower her expectations. Still, she’d at least like to see the face of the man she’ll be spending the rest of her life with and so she sneaks out of the palace and goes investigating. Her first ventures outside of the walls which have protected her all her life are marked by a sense of magical freedom, though what she sees there later shocks her. Her subjects starve, and blame her for their starving. Lamenting the poor nobleman who will be taking one for the team in marrying the notoriously ugly and difficult Princess Songhwa, they pray for her wedding day and the rain they fully expect to fall.

Given all of this ill feeling towards the princess, it doesn’t take much to guess what sort of men are prepared to toss their hats into the ring. The suitors may look attractive on the surface, as Songhwa discovers, but each has faults not visible in his stars. One is a child, another a womanising playboy. It comes to something when the worst possible match isn’t the murderous psycho posing a philanthropist but the ambitious social climber who will stop at nothing to advance his cause.

Some might say the sacred art of divination is a bulwark against court intrigue, but this like anything else is open to manipulation. The king’s old astronomer has been taking bribes for years – something brought to light by ace investigator with a talent for divination Seo Do-yoon (Lee Seung-gi) with help from shady street corner soothsayer Gae-shi (Jo Bok-rae). Appointed to the position himself, Seo unwittingly holds the keys to Songhwa’s future though that isn’t something he’d given particular consideration to. His job was just to read the charts before everything started getting needlessly complicated. When his list of candidates goes missing he has no choice but to start visiting the ones he can remember in person which is how he ends up repeatedly running into Songhwa in disguise and, despite himself, beginning to fall in love with her.

Songhwa, trapped in a golden cage, longs to live a life of her own free from the patriarchal demands of a hierarchical society. She bucks palace authority by sneaking out on her own, but never seriously attempts to avoid her miserable fate or resist the tyranny of an arranged marriage, only to be allowed foreknowledge of the kind of life for which she has been destined. Nevertheless, determining her own future later becomes something within her grasp once the corruption has been uncovered and the art of prophecy exposed for what it is. Destiny is more malleable than it first seems and as Seo advises the king, when compassion reigns the heavens will open. True harmony is not born of a rigid adherence to facts and figures assigned by the arbitrary conditions of birth, but by a careful consideration of the feelings of others. A life without love is as starved as one without rain and the truly harmonious kingdom is the one in which all are free to feel it fall where it may.

The Princess and the Matchmaker was screened as part of the 2018 London Korean Film Festival.

International teaser trailer (English subtitles)

Following on from the

Following on from the  Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student.

Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student. Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman.

Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman. Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval.

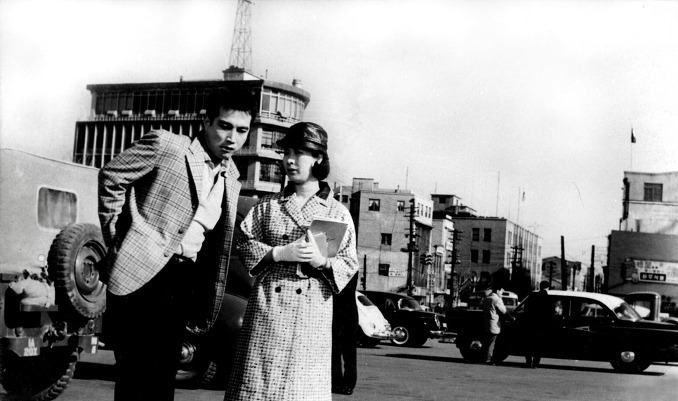

Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval. Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.

Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.  Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women.

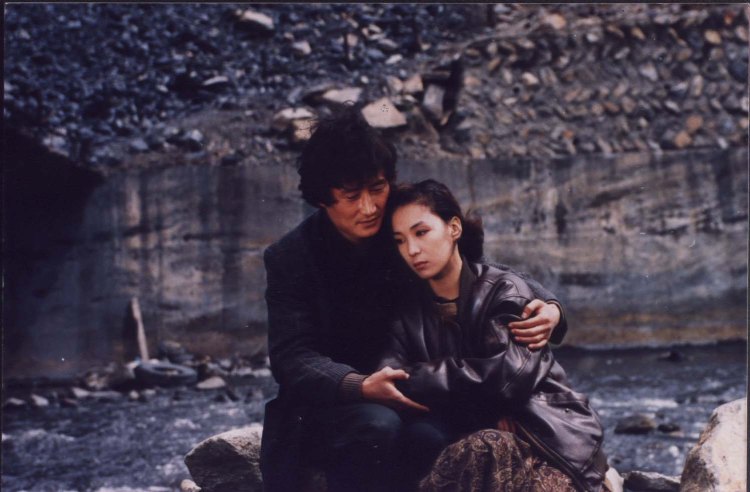

Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women. Park Kwang-su revisits the democratisation movement in its immediate aftermath as a student who hides from the authorities in a small mining village finds himself at odds with his environment while haunted by the possibility that his longed for revolution will not come to pass.

Park Kwang-su revisits the democratisation movement in its immediate aftermath as a student who hides from the authorities in a small mining village finds himself at odds with his environment while haunted by the possibility that his longed for revolution will not come to pass.

After a brief pause, the

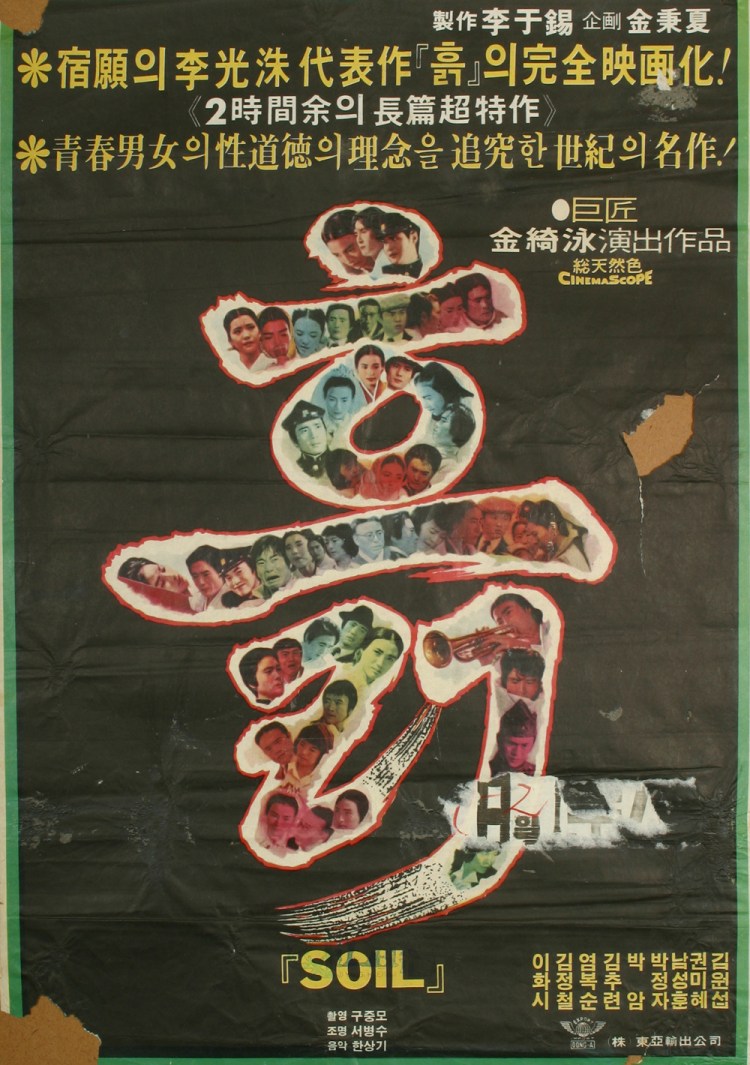

After a brief pause, the  Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

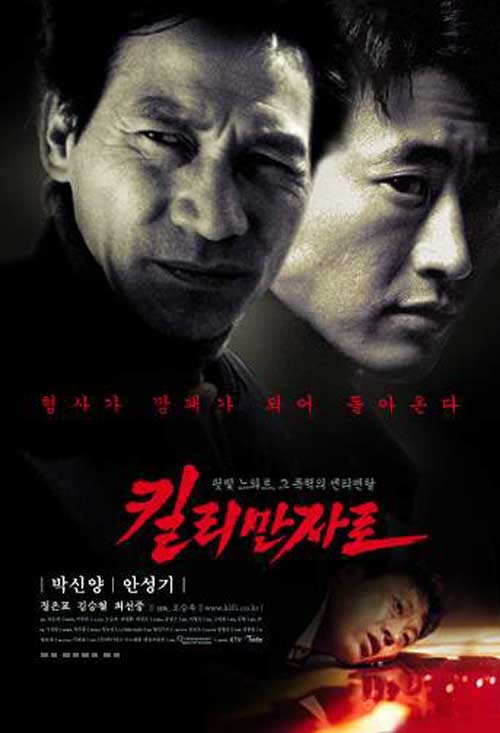

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life.

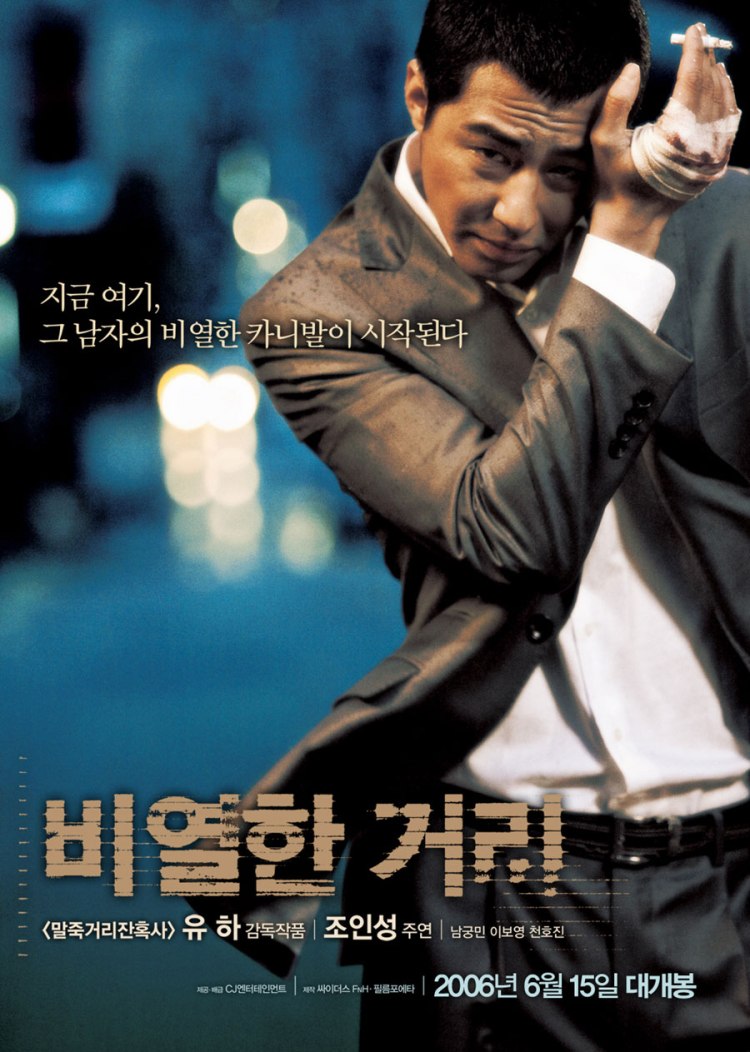

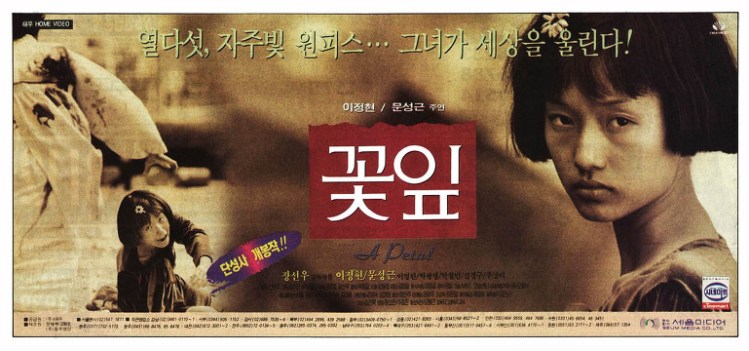

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life. Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her.

Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her. Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains.

Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains. The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer.

The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer. An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.

An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.