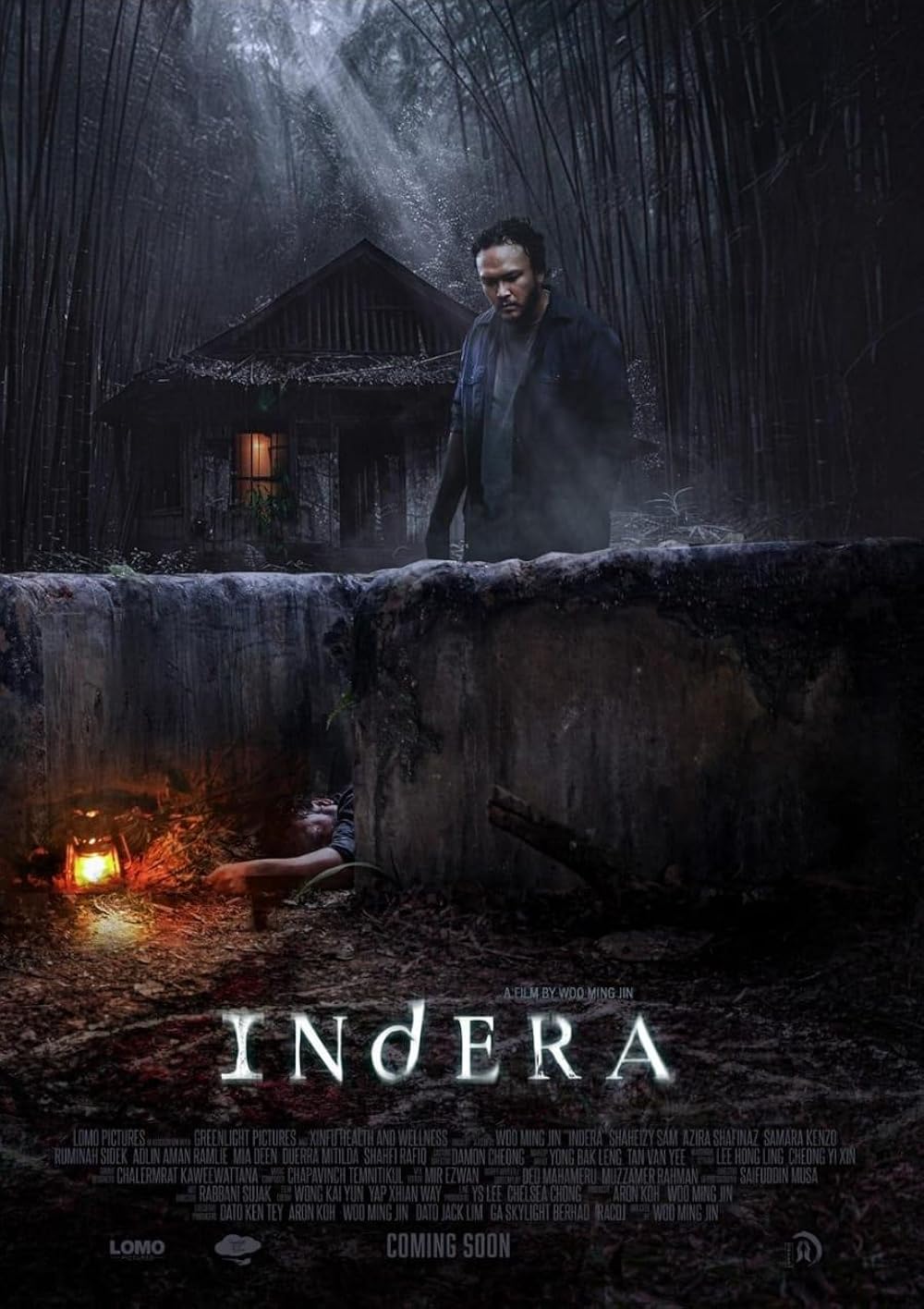

“Let’s leave this place,” a father tearfully tells his daughter, “we’ll find a better home,” but it seems the girl has found her home already and no longer wishes to leave in Woo Ming Jin’s eerie folk horror, Indera. In many ways about coming to terms with loss and grief, the film also explores tensions within the contemporary society through allusions to the 1985 Memali Incident in which political tensions in the country culminated in the siege of a village resulting the deaths of 14 villagers and four policemen.

The film begins however nine years earlier with Joe driving his pregnant wife Anisa down a country road only for the engine to overheat. Joe gets out to find some water leaving his wife alone, but his stabbing of a beetle for his collection on the way back seems to provoke some strange event. On returning to the car he finds Anisa gone, and flashing forward to the present day we can see that he is now a single father to Sofia who has been mute since birth but is able to hear.

Ironically, present day action opens with her refusing to open a door though she will later be told not to listen when a mysterious force calls her name only to ignore the warning. This time she avoids answering because she suspects it’s debt collectors. Lost in his grief, Joe appears to be living in financial difficulty and is far behind with his rent. They’ve run out of food, which is why Sofia has eaten only sweets, which she seems to be rationing, for breakfast. Joe tells her that they have to protect their castle like in the fairytale Sofia is fond of reading, but in fact the pair are soon kicked out with otherwise sympathetic landlord Haji giving them a tip off about another job as a live-in handyman for a Javanese shamaness living way out in the country. On their arrival however, it’s clear that there is something very odd going on that neither of them really understand.

Nevertheless, the old woman’s home is a kind of liminal space that comes to represent Joe’s unresolved grief. The old woman, who asks to be addressed as “Mother,” asks him if he’s heard about what’s going on in Memali, and he admits he has but that it’s none of his business. Mother agrees that there’s no need to become involved in the affairs of others, but also ominously points to her birds and asks if a blind bird knows that it is caged. The same could be asked of Joe as his fate and that of the King in Sofia’s fairytale become intertwined while she progresses towards a destiny that is out of his control. Encountering a spirit that seems to be that of his late wife, Joe is forced to face his paternal anxiety and the fact that on some level he may have been responsible for what happened to Anisa while also resentful towards Sofia as a child he may not have wanted whom he also blames for her loss.

Perhaps Mother knows all this already, telling Joe that everyone has their sickness and she’s worked out what his is already though he cannot seem to see hers nor what the ominous hole she seems to be worshipping may represent. She claims that the children she has with her in the former orphanage that is her home were all “unwanted,” as Sofia may also have been and Anisa too, but has a dark purpose for them that Joe is ill equipped to understand. The hole comes to represent the bottomless pit of his grief and regret, but the spirits are also echoes of the forces of authoritarianism haunting Memali in which the children are told not to look back or answer if something calls their name and on no account ever to venture near the hole.

Still, Sofia can’t help being curious and the hole may come to represent something else to her while Joe struggles to understand his relationship with his daughter, seeing her perhaps as a manifestation of his own transgression and ultimately an embodiment of evil that it is his duty to destroy. Eerie in its palpable sense of dread, Woo Ming Jin’s oblique folk horror is pregnant with political allegory and locates its most chilling moment in Sofia’s insistence that “this is our home” in the suggestion that in the end there is no “better home” to go to but only this inescapable hell.

Indera screens in Chicago 28th March as part of the 19th edition of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Trailer