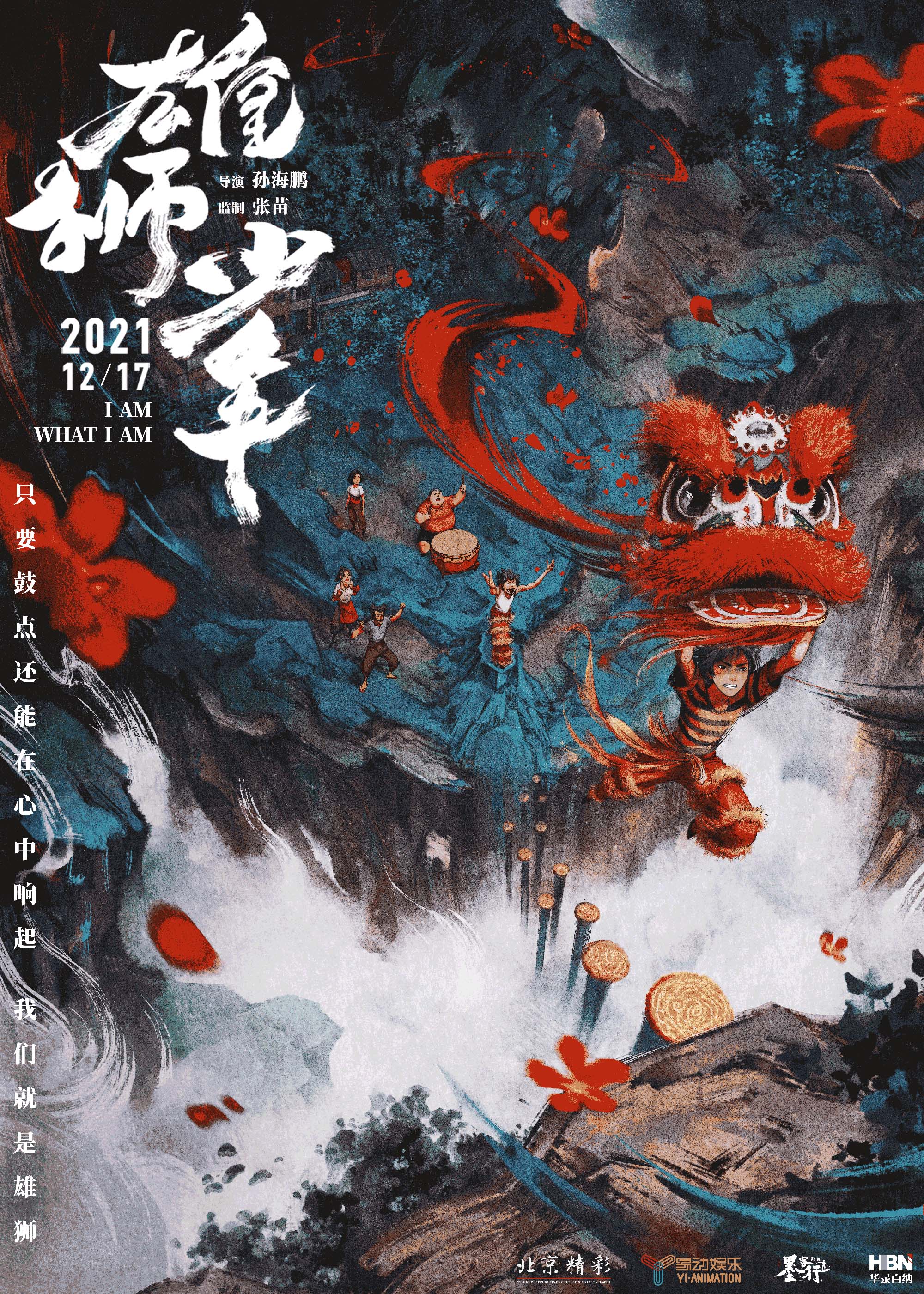

A diffident young man learns to unleash the lion inside while battling the fierce inequality of the modern China in Sun Haipeng’s heartfelt family animation, I Am What I Am (雄狮少年, xióngshī shàonián). With its beautifully animated opening and closing sequences inspired by classic ink painting and the enormously detailed, painterly backgrounds, the film is at once a celebration of tradition and advocation for seizing the moment, continuing to believe that miracles really are possible even for ordinary people no matter how hopeless it may seem.

The hero, Gyun (Li Xin), is a left behind child cared for by his elderly grandfather and it seems regarded as a good for nothing by most of the local community. Relentlessly bullied by a well built neighbour who is also a talented lion dancer, Gyun finds it impossible to stand up for himself but is given fresh hope by a young woman who makes a dramatic entrance into the village’s lion dance competition and later gifts him her lion head telling him to listen to the roar in his heart.

The young woman is presented as an almost spiritual figure embodying the lion dance itself, yet later reveals that her family were against her practicing the traditional art because she is female exposing the persistent sexism at the heart of the contemporary society. Gyun’s heart is indeed roaring, desperately missing his parents who were forced to travel to the city to find work while leaving him behind in the country hoping to earn enough for his college education. Part of the reason he wants to master the art of the lion dance is so that he can travel to the city where his parents can see him compete, while privately like his friends Kat and Doggie he may despair for his lack of options stuck in his small hometown.

But even in small towns there are masters of art as the boys discover when directed to a small dried fish store in search of a once famous lion dancer. Perhaps the guy selling grain at the market is a master poet, or the local fisherman a talented calligrapher, genius often lies in unexpected places. Now 45, Qiang (Li Meng) is a henpecked husband who seems to have had the life-force knocked out of him after being forced to give up lion dancing in order to earn money to support his family, but as the film is keen to point out it’s never really too late to chase a dream. After agreeing to coach the boys, Qiang begins to reclaim his sense of confidence and possibility with even his wife reflecting that she’s sorry she made him give up a part of himself all those years ago.

Then again, Gyun faces a series of setbacks not least when he’s forced to travel to the city himself in search of work to support his family taking his lion mask with him but only as an awkward burden reminding him of all he’s sacrificing. Taking every job that comes, he lives in a series of squalid dorms and gradually begins to lose the sense of hope the lion mask granted him under the crushing impossibility of a life of casual labour. The final pole on the lion dance course is there, according to the judges, to remind contestants that there are miracles which cannot be achieved and that there will always be an unreachable peak that is simply beyond them. But as Gyun discovers sometimes miracles really do happen though only when it stops being a competition and becomes more of a collective liberation born of mutual support.

In the end, Gyun can’t exactly overcome the vagaries of the contemporary society, still stuck in a crushing cycle of poverty marked by poor living conditions and exploitative employment, but he has at least learned to listen to himself roar while reconnecting with his family and forming new ones with friends and fellow lion dancers. While most Chinese animation has drawn inspiration from classic tales and legends, I Am What I Am roots itself firmly in the present day yet with its beautifully drawn backgrounds of verdant red forests lends itself a mythic quality while simultaneously insisting that even in the “real” world miracles can happen even for lowly village boys like Gyun when they take charge of their destiny not only standing up for themselves but for others too.

I Am What I Am screens in Chicago on Sept. 10 as the opening movie of Asian Pop-Up Cinema season 15.

Original trailer (English subtitles)