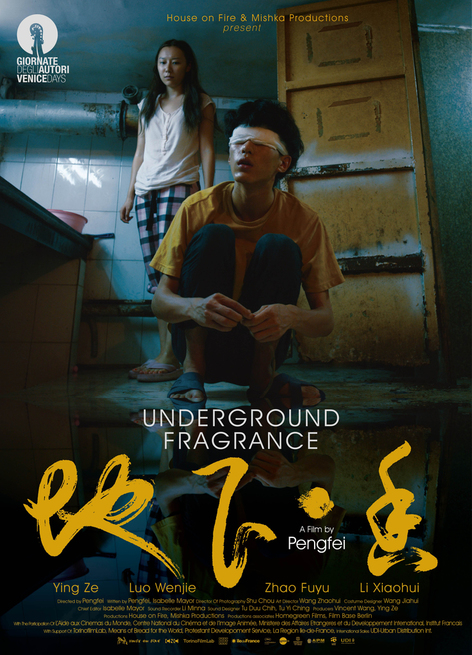

The original Chinese title of recent Tsai Ming-liang collaborator (Song) Pengfei’s debut feature 地下・香 (dìxìa・xiāng) has an intriguing full stop in the middle which the English version loses, but nevertheless these two concepts “underground” and “fragance” become inextricably linked as the four similarly trapped protagonists desperately try to fight their way to better kind of life. Recalling Tsai’s dreamy symbolism, Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s romantic melancholy, and Jia Zhangke’s lament for the working man lost in China’s rapidly changing landscape, Pengfei’s film is nevertheless resolutely his own as it chases the ever elusive Chinese dream all the way from dank basements and ruined villages to the shiny high rise cities which promise a tomorrow they may never be able to deliver.

The original Chinese title of recent Tsai Ming-liang collaborator (Song) Pengfei’s debut feature 地下・香 (dìxìa・xiāng) has an intriguing full stop in the middle which the English version loses, but nevertheless these two concepts “underground” and “fragance” become inextricably linked as the four similarly trapped protagonists desperately try to fight their way to better kind of life. Recalling Tsai’s dreamy symbolism, Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s romantic melancholy, and Jia Zhangke’s lament for the working man lost in China’s rapidly changing landscape, Pengfei’s film is nevertheless resolutely his own as it chases the ever elusive Chinese dream all the way from dank basements and ruined villages to the shiny high rise cities which promise a tomorrow they may never be able to deliver.

Yong Le (Luo Wenjie) is just one such young man, trying to buy a future by raiding the past. He has a small van he uses to “reclaim” furniture and sell it second hand. One day he has an accident whilst working which costs him his sight. Finding it difficult to manage in the cramped, noisy corridors of the subterranean cavern he is currently living in, Yong Le strikes up a friendship with his kindly new next door neighbour, Xiao Yun (Ying Ze), who helps him with some of his everyday problems like telling the time and finding food. Xiao Yun is currently working as a pole dancer in a seedy club which she longs to quit and is hoping to bag a salesgirl position at a new development office.

Yong Le is also friends with an older man, Lao Jin (Zhao Fuyu), who lives above ground with his wife (Li Xiaohui) in a large, old fashioned courtyard style house. Lao Jin and his wife are the only remaining residents of the village, the rest of which has been knocked down already after the other homeowners settled with the development company for what they considered the best deal they could get. Lao Jin, however, thinks it’s worth holding out and has been “in negotiations” for eight years. Dreaming of a mega payout he can use to by a fancy city flat and be a big shot at last, Lao Jin has already run through his savings and is dangerously close to losing everything.

In a rather pointed piece of symbolism, Xiao Yun walks past a large mural with the slogan “Run Towards Your Dreams” prominently displayed in the middle. Later, this same wall will be reduced to rubble, a handful of brightly coloured stones marking the spot where once a village stood. Xiao Yun and Yong Le have very different dreams to those of Lao Jin, reflecting the way that even aspiration has shifted with the generations. He wants the fancy penthouse life for himself and his wife, even if it means selling their furniture and sacrificing his wife’s beloved white rooster, but all Yong Le and Xiao Yun want is out of the dingy basement and into a cleaner sort of life.

Yong Le and Xiao Yun may begin to fall in love during his period of blindness, but it’s a luxury neither of them can afford. There’s a slight irony in the fact that Xiao Yun who’s come to hate the men who visit her bar, some of them trying to buy more than a show, becomes attached to a man who cannot see her, but her desperation to escape her dead end life before it’s too late means she can’t afford to hang around for romance to bloom. A heart stopping moment sees the sight restored Yong Le unexpectedly end up at the bar where Xiao Yun dances, but having been blind the entire time he knew her, he doesn’t recognise the woman on stage (though to his credit he does not particularly look). Pulled apart by the increasing harshness of the economic environment, romance is an unattainable dream for those like Yong Le and Xiao Yun, drifting around from one thing to the next barely able to touch the ground let alone live on it.

Pengfei’s camera operates with a formalist grace, putting architecture at the forefront of his storytelling. From the ruins of a village to lie of the as yet unfinished high-rise future and the dank, dangerous underground world of the casual drifters always aiming for something better, the landscape gives voice to the often despairing nature of life on edges of a society where the rate of change threatens to leave vast swathes of its citizens behind. Adding a touch of the surreal such as a supremely timed return of the electricity in which Lao Jin’s attempt to oust a noisy owl with fireworks lines up with his peking opera record, or the couple’s later attempt to woo the developers with a musical performance of their own (another demonstration of the way their old world customs have become obsolete), Pengfei undercuts the ever present melancholy with a dose of whimsical irony. Wistfully romantic, and dreaming of a better, fairer society Underground Fragrance is a snapshot of a world in flux in which even the most essential of human connections can become lost in the crowd of faces all running towards tomorrow.

Currently screening for free on Festival Scope as part of their Torino Film Lab selection.

Trailer from Venice (English subtitles)

Set in 1984 in a rural Chinese backwater, De Lan (德蘭) is named not for its central character, but for his first love – a mountain woman far from home in search of a missing relative. Tasked with following De Lan (De Ji), Wang (Dong Zijian) finds himself entering a strange new world which he is incapable of fully understanding, not least because he doesn’t speak the language. A wordless love story between the tragic De Lan and the adolescent Wang is destined to end unhappily, but will affect both of them in quite profound ways.

Set in 1984 in a rural Chinese backwater, De Lan (德蘭) is named not for its central character, but for his first love – a mountain woman far from home in search of a missing relative. Tasked with following De Lan (De Ji), Wang (Dong Zijian) finds himself entering a strange new world which he is incapable of fully understanding, not least because he doesn’t speak the language. A wordless love story between the tragic De Lan and the adolescent Wang is destined to end unhappily, but will affect both of them in quite profound ways. Despite its title, Mission Milano (王牌逗王牌, Wángpái Dòu Wángpái) spends relatively little time in the Northern Italian city and otherwise bounces back and forth over several worldwide locations as bumbling Interpol agent Sampan Hung (Andy Lau) chases down a gang of international crooks trying to harness a new, potentially world changing technology. Inspired by the classic spy parodies of old, Wong Jing’s latest effort proves another tiresome attempt at the comedy caper as its nonsensical plot and overplayed broad humour resolutely fail to capture attention.

Despite its title, Mission Milano (王牌逗王牌, Wángpái Dòu Wángpái) spends relatively little time in the Northern Italian city and otherwise bounces back and forth over several worldwide locations as bumbling Interpol agent Sampan Hung (Andy Lau) chases down a gang of international crooks trying to harness a new, potentially world changing technology. Inspired by the classic spy parodies of old, Wong Jing’s latest effort proves another tiresome attempt at the comedy caper as its nonsensical plot and overplayed broad humour resolutely fail to capture attention. First time writer/director Wang Yichun draws on her own experiences for What’s in the Darkness (黑处有什么, Hei chu you shenme), a beautifully shot coming of age piece with serial killer intrigue running in the background. Seen through the eyes of its protagonist, What’s in the Darkness neatly matches the heroine’s journey into adolescence with the changing nature of Chinese society.

First time writer/director Wang Yichun draws on her own experiences for What’s in the Darkness (黑处有什么, Hei chu you shenme), a beautifully shot coming of age piece with serial killer intrigue running in the background. Seen through the eyes of its protagonist, What’s in the Darkness neatly matches the heroine’s journey into adolescence with the changing nature of Chinese society. When

When  Hur Jin-ho’s A Good Rain Knows (호우시절, Howoosijeol) was originally developed as a short intended to form part of the China/Korea collaborative omnibus film Chengdu, I Love You which was created as a tribute to the area following the devastating 2008 earthquake. However, Hur came to the conclusion that his tale of modern day cross cultural romance required more scope than the tripartite omnibus structure would allow and decided to go solo (Chengdu, I Love You was later released with just Fruit Chan and Cui Jian’s efforts alone). Very much Korean in terms of tone and structure, Hur uses his central love story to explore the effects time, memory, culture, and personal trauma on the lives of everyday people.

Hur Jin-ho’s A Good Rain Knows (호우시절, Howoosijeol) was originally developed as a short intended to form part of the China/Korea collaborative omnibus film Chengdu, I Love You which was created as a tribute to the area following the devastating 2008 earthquake. However, Hur came to the conclusion that his tale of modern day cross cultural romance required more scope than the tripartite omnibus structure would allow and decided to go solo (Chengdu, I Love You was later released with just Fruit Chan and Cui Jian’s efforts alone). Very much Korean in terms of tone and structure, Hur uses his central love story to explore the effects time, memory, culture, and personal trauma on the lives of everyday people. Evil, so a wise man said, begins when you start treating people as things. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis showed us a city that literally was its people – nothing but a vast yet perfectly functional machine with the workers little more than cogs to be replaced and discarded once worn out. Zhao’s Behemoth (悲兮魔兽, Bēixī Móshòu) is no fantasy but a very real journey through our own world and so we follow our narrator, a poetic, naked stand in for Dante’s Virgil, through hell and purgatory on a path to paradise only to find ourselves staring into a void filled with our unfulfilled desires and forlorn hopes.

Evil, so a wise man said, begins when you start treating people as things. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis showed us a city that literally was its people – nothing but a vast yet perfectly functional machine with the workers little more than cogs to be replaced and discarded once worn out. Zhao’s Behemoth (悲兮魔兽, Bēixī Móshòu) is no fantasy but a very real journey through our own world and so we follow our narrator, a poetic, naked stand in for Dante’s Virgil, through hell and purgatory on a path to paradise only to find ourselves staring into a void filled with our unfulfilled desires and forlorn hopes. The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics. Chinese cinema screens are no stranger to the event movie, and so a Chinese remake of the much loved 1997 Hollywood rom-com My Best Friend’s Wedding (我最好朋友的婚礼, Wǒ Zuì Hǎo Péngyǒu de Hūnlǐ) arrives right on time for Chinese Valentine’s Day. Purely by coincidence of course! However, those familiar with the 1997 Julia Roberts starring movie may recall that My Best Friend’s Wedding is a classic example of the subverted romance which doesn’t end with the classic happy ever after, but acts as a tonic to the sickly sweet love stories Hollywood is known for by embracing the more realistic philosophy that sometimes it just really is too late and you have to accept that you let the moment get away from you, painful as that may be.

Chinese cinema screens are no stranger to the event movie, and so a Chinese remake of the much loved 1997 Hollywood rom-com My Best Friend’s Wedding (我最好朋友的婚礼, Wǒ Zuì Hǎo Péngyǒu de Hūnlǐ) arrives right on time for Chinese Valentine’s Day. Purely by coincidence of course! However, those familiar with the 1997 Julia Roberts starring movie may recall that My Best Friend’s Wedding is a classic example of the subverted romance which doesn’t end with the classic happy ever after, but acts as a tonic to the sickly sweet love stories Hollywood is known for by embracing the more realistic philosophy that sometimes it just really is too late and you have to accept that you let the moment get away from you, painful as that may be. Often, people will try to convince of the merits of something or other by considerably over compensating for its faults. Therefore when you see a movie marketed as the X-ian version of X, starring just about everyone and with a budget bigger than the GDP of a small nation you should learn to be wary rather than impressed. If you’ve followed this very sage advice, you will fare better than this reviewer and not find yourself parked in front of a cinema screen for two hours of non-sensical European fantasy influenced epic adventure such as is League of Gods (3D封神榜, 3D Fēng Shén Bǎng).

Often, people will try to convince of the merits of something or other by considerably over compensating for its faults. Therefore when you see a movie marketed as the X-ian version of X, starring just about everyone and with a budget bigger than the GDP of a small nation you should learn to be wary rather than impressed. If you’ve followed this very sage advice, you will fare better than this reviewer and not find yourself parked in front of a cinema screen for two hours of non-sensical European fantasy influenced epic adventure such as is League of Gods (3D封神榜, 3D Fēng Shén Bǎng).