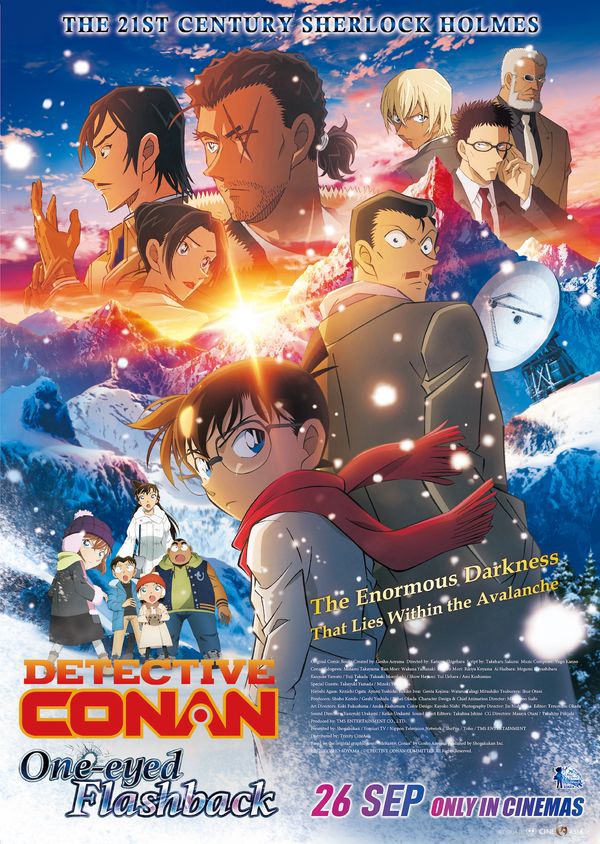

Detective Conan (Minami Takayama) returns for the 28th instalment in the long-running animated film series, Detective Conan: One-Eyed Flashback, (名探偵コナン 隻眼の残像(フラッシュバック), Meitantei Conan: Sekigan no Flashback) as he finds himself embroiled in another mystery revolving around Inspector Yamato’s (Yuji Takada) near fatal collision with an avalanche, a potential terrorist attack on a radio observatory, and the murder of one of Kogoro Mori’s (Rikiya Koyama) old friends. Meanwhile, justice is under fire as the government are working on reforming the plea deal system which leaves some feeling short-changed by justice and that the criminals are getting off too lightly while victims of crime continue to suffer.

Indeed, there’s a kind of symmetry between Conan’s guardian Kogoro, who took him in after he was shrunk to the size of a child by the evil Black Organisation, and bereaved father Funakubo who blames himself for what happened to his daughter Maki because he sent her back to his gun shop where she got caught up in a robbery. Before she left, she said she had something to tell him, but he never got to hear what it was, just as Kogoro never heard what his former colleague from his police days, Croco, wanted to tell him when he set up a clandestine meeting in a local park but was killed by a mysterious assassin before he could say anything.

Once again, Conan is on the case, though Kogoro more or less sidelines him and insultingly repeatedly reminds Conan that this is not a game. Nevertheless, Inspector Yamato specifically asks for his help, while Conan begins to suspect something bigger is motion when he’s unsubtly bugged by someone he assumes is probably an undercover Public Security officer. All roads lead back to Amuro (Takeshi Kusao), who handles the situation from the cafe in Tokyo where he works to maintain his cover identity.

Nevertheless, it all links back to the gun shop robbery and its lingering effects on the victims. Not only was one of the thieves not caught, but the other got off on a plea bargain which has left Mr Funakubo on a constant quest for justice in which he is forever hassling the Nagano Police for updates on his case. Meanwhile, there’s interpersonal drama in play in the relationship between police officers Yamato and Yui (Ami Koshimizu) who are also wrestling with unspoken feelings and the fallout from Yamato’s presumed death in the avalanche in which he lost his memory and wasn’t found until a few months later. The wound to his eye is symbolic of his inability to recall the whole of what happened before he was overcome by the snow. He must have seen the face of the man he was chasing at the time, but he can’t remember it.

Though the mystery itself may not be as complicated as others in the series, involving few clues or difficult puzzles to be solved and relying instead on Conan’s keen intuition and people skills, it leans heavily into a sense of conspiracy and paints Public Security in an unflattering light as they attempt to bug Conan and then in a post-credits scene, are seen to offer another “plea deal” to a suspect in return for keeping Public Security out of their testimony while blackmailing them that, should they choose to speak out, all their secrets will also be revealed to the public and those close to them will suffer. In any case, Conan gets a few more opportunities to use his all-powerful skateboard amid the film’s increasingly elaborate action sequences as he squares off against the crazed villain hellbent on vengeance and an ironic defence of the law.

Where Public Security come in for scrutiny, the police are depicted as universally good, reminding the suspect that it’s the police’s job the enforce the law without fear or favour while protecting ordinary people both physically and emotionally. As messages go, it might be a little authoritarian, but it’s also true that the police take Conan seriously in ways others may not. While they’re all busy with the crime(s), Conan’s friends are also all in Nagano along with Ran (Wakana Yamazaki) enjoying what’s supposed to be a stargazing holiday before being dragged into the case and providing important backup for Conan. As the tagline says, the truth won’t stay buried forever and Conan does his best to play off Public Security and the police in order to solve the case, avenge Kogoro’s friend, and also protect justice in Japan as the courts debate the plea bargain issue and its effect on criminals and victims alike as they try to rebuild their lives in the wake of crime.

Detective Conan: One-Eyed Flashback is in UK cinemas from 26th September courtesy of CineAsia.

Trailer (Japanese / Traditional Chinese subtitles)