Employees at a small nude modelling agency find themselves in the firing line when a “bloodsucking painter” escapes from a psychiatric institution in Motoyoshi Oda’s adaptation of Seishi Yokomizo’s Ghost Man (幽霊男, Yurei Otoko). Though produced by Toho and helmed by the director of The Invisible Man, the film does not particularly make use of special effects and as it turns out, Ghost Man is just a creepy name for a weird villain rather than an accurate description of a supernatural threat.

Even so, you’d expect someone who runs a modelling agency to be on high alert after hearing that a crazed painter who is a danger to women is on the loose, but the manager of the Mutual Art Club simply assumes it must be an eccentric artist thing when he’s presented with a business card from “Ghost Man” Sugawa. Ghost Man is dressed in an unsettling outfit and is immediately rough with the model he picks out, Keiko, all of which you would think would have the manager thinking twice about allowing her to go with him. Some of the other girls urge her to turn the job down, but Keiko is the breadwinner for her family and work has been thin on the ground so she agrees to take it only to realise Ghost Man does indeed intend to kill her on arrival at an abandoned house way out in the country.

“What a single woman has to do to earn a living, it’s both thrilling…and terrifying,” one of the other women, Ayuko, tells her boyfriend Ken (Yu Fujiki) after she quits the agency to become a stripper and decides to take to the stage despite knowing that Ghost Man may try to kill her during the show. Her words hint at a transgressive frisson of danger which she at least has chosen to embrace, an icy glint in her eye as she encourages Ken to pay close attention to her performance which she claims will be “wonderful”. Nevertheless, it also makes clear that the work the women do at the agency is necessarily unsafe given that it involves travelling to the home of a man they don’t know where they will be expected to undress.

For reasons the film doesn’t quite explain, the models are also members of the “Bizarro Enthusiast Club” led by Dr. Kano (Joji Oka) who is the head doctor at the psychiatric hospital from which the bloodsucking painter, Tsumura (Ren Yamamoto), escaped. Meanwhile, Dr. Kano also seems to have a sideline in taking the girls to remote locations for nude photoshoot parties. In all honesty, he’s quite suspicious especially seeing as he seems to instinctively know how to open the tricky door at the abandoned house where Keiko’s body is found. Then again, we’re also told that Tsumura was once a member of the club with at least some suggesting that he ended up getting too into the bizarre and going out of his mind to the extent that he began committing weird acts of crime of his own.

The lesson might be that getting overly obsessed with the occult and esoteric is unhealthy, only it turns there’s something else going on entirely that isn’t really about anything “weird” but caused by completely banal negative human emotions resulting from spurned romantic interest and the fear of parental disappointment. This being a Kindaichi mystery, the famous detective soon makes his appearance (played by a hardboiled Seizaburo Kawazu) only in a less eccentric guise and accompanied by a more efficient Todoroki who assists him as he begins to put the pieces together to solve the mystery.

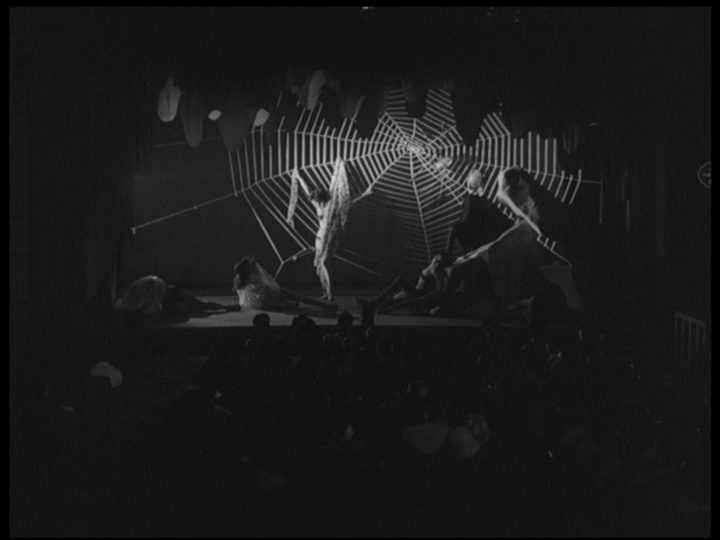

The villain may be taking advantage of a historical moment in allowing others to think his face is bandaged to disguise a disfigurement like those of many men wounded in the war, as was the case in another Kindaichi case The Inugami Family, but is also harking back to the Invisible Man while his accomplice adopts a much more “monstrous” appearance with buck teeth and the two missing fingers on his hand along with the insectile movements that play into the spider-themed finale. Oda has a lot of fun with the villain’s Phantom of the Opera-esque antics which include recording a tape to taunt the police along with a public announcement of “Act 3” of his ongoing drama to be staged at the “Reijin Theatre” which literally means “the beautiful lady show” but is also a minor pun that makes it sound a little “Ghost Man Theatre” in true B-movie villain fashion. Even so, there’s an underlying darkness in the serial killer drama most particularly in the scrapbook the villain makes with photos of the dead women posed and titled as works of art as if they were never any more alive than the mannequins he often substitutes for them. Striking in its set pieces and unsettling design, Oda’s strange drama is surprisingly nasty and actually quite cynical even as it unmasks its villain as little more than a ghost of man who hid behind the spectre of unease to mask his cowardice and insecurity.

The Invisible Man is a frightening presence precisely because he isn’t there. The living manifestation of the fear of the unknown, he stalks and spies, lurking in our imaginations instilling terror of evil deeds we are powerless to stop. Daiei made

The Invisible Man is a frightening presence precisely because he isn’t there. The living manifestation of the fear of the unknown, he stalks and spies, lurking in our imaginations instilling terror of evil deeds we are powerless to stop. Daiei made