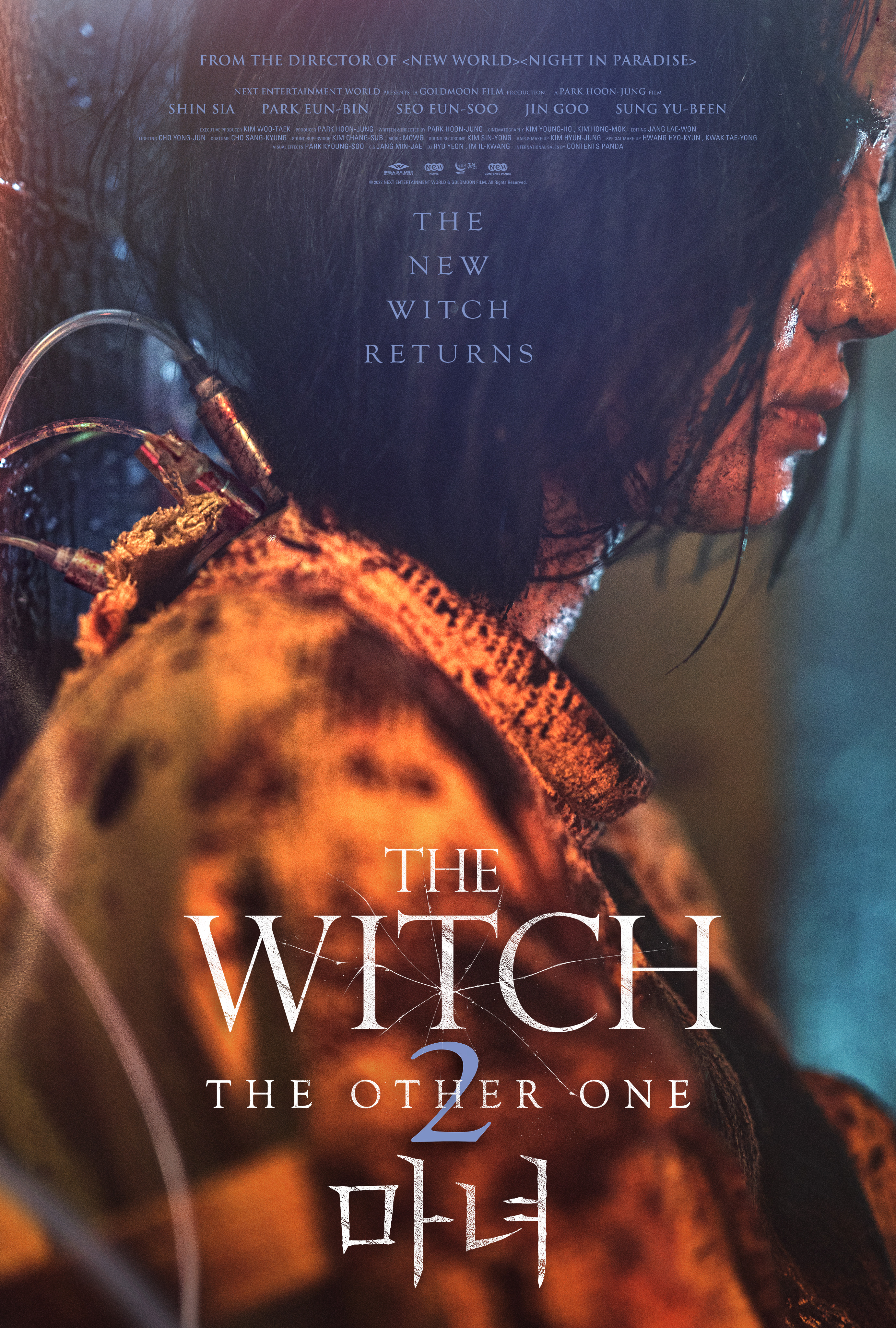

In Park Hoon-jung’s The Witch: Part 1.The Subversion, a young woman managed to escape a shady research facility to live as a regular high schooler while her adoptive parents wondered if their love for her could cure the violence with which she had been nurtured. Four years on, Hoon returns with Part 2: The Other One (마녀 2, Manyeo 2) which as the title implies follows another girl who similarly escapes her captivity and fetches up on a farm where she forms a surrogate family with a brother and sister in immediate danger of displacement.

Unlike the first film’s Ja-yoon (Kim Da-mi) who rebuilt a life of “normality” after seemingly losing her memory, the unnamed girl emerges into a confusing and unfamiliar world in which everything is new to her. Challenged by a shady gang of guys on a highway, she’s bundled into a car which is where she encounters Kyung-hee (Park Eun-bin), a young woman kidnapped by a former associate of her late father who plans to murder her and steal her land for a lucrative construction project. Realising what might be in store for her, Kyung-hee tries to protect the girl and urges the gangsters to let her go before the girl decides to protect Kyung-hee in return by using her special abilities to total the car and set them both free. The girl is just about to finish off one of the mobsters when Kyung-hee tells her that she doesn’t need to, starting her on a path to questioning the indiscriminate violence with which she has been raised even as she determines to continue protecting Kyung-hee and later her brother Dae-gil (Sung Yoo-bin) who are now caught between the venal gangsters and an international conspiracy with various groups of people intent on either kidnapping or eliminating the escaped test subject.

As had been hinted at in the previous film’s conclusion, there is a definite preoccupation with twins but also with internal duality. The shady corporation hints that the girl may be an upgraded edition, the “perfect model” of transhumanism, yet she appears less amoral than the unmasked Ja-yoon almost always seeking to incapacitate rather than kill while determined to protect Kyung-hee at any cost. To begin with, she is largely unable to speak but reacts with wide-eyed wonder to outside world visibly stunned by the wide open spaces on her way to the farm and develops a fascination with food eager to try anything and everything charging round a supermarket eating all the free samples while piling the trolley high with snacks.

Like Ja-yoon however and in a superhero cliché she finds refuge on a farm and helps to complete the family which had been ruptured by absence but her new happiness is fragile on several levels not least of them that the farmhouse is under threat from venal gangster Yong-du (Jin Goo) who wants the land to build a resort. In an undeveloped plot strand, it seems that Dae-gil has lingering resentment towards his sister for leaving for America and returning only when their father died with the intention of sorting out the estate while it otherwise seems clear that their father was himself a gangster who may have used his ill-gotten gains to buy the farm in the first place. This is no ordinary rural backwater, but one brimming with darkness as the backstreet doctor turned drunken vet makes clear.

In another duality, the girl is chased by a series of opposing forces split between “union” and “transhumanism” and represented by mercenary Sgt. Cho (Seo Eun-soo) and her South African partner (Justin John Harvey) and a gang of Chinese vigilantes from the Shanghai lab who are looking for the girl to get her to join them. Like the girl, the mercenaries appear to act with a code of ethics, trying their best to avoid civilian casualties while viewing death as a last resort while the ruthless vigilantes rejoice in violent brutality. In any case Park leaves the door open for a further continuation of the series in which the two women search for their shared origins in the hope of a literal, physical salvation but also perhaps the answer to a mystery long withheld from them. With a series of large scale and well choreographed action sequences, Park builds on the first film’s success and quite literally tells a sister story as “the other one” pursues her mirror image destiny while ironically finding beauty in the fireworks of a volatile society.

The Witch: Part 2. The Other One screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival and is released in the US courtesy of Well Go USA.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Images: Courtesy of Well Go USA Entertainment