When Library Wars, the original live action adaptation of Hiro Arikawa’s light novel series, hit cinema screens back in 2013 it did so with a degree of commercial, rather than critical, success. Though critics were quick to point out the great gaping plot holes in the franchise’s world building and a slight imbalance in its split romantic comedy/sci-fi political thriller genre mix, the film was in many ways a finely crafted mainstream blockbuster supported by committed performances from its cast and impressive cinematography from its creative team. Library Wars: The Last Mission (図書館戦争-THE LAST MISSION-, Toshokan Senso -The Last Mission-) is the sequel that those who enjoyed the first film have been waiting for given the very obvious plot developments left unresolved at the previous instalment’s conclusion.

When Library Wars, the original live action adaptation of Hiro Arikawa’s light novel series, hit cinema screens back in 2013 it did so with a degree of commercial, rather than critical, success. Though critics were quick to point out the great gaping plot holes in the franchise’s world building and a slight imbalance in its split romantic comedy/sci-fi political thriller genre mix, the film was in many ways a finely crafted mainstream blockbuster supported by committed performances from its cast and impressive cinematography from its creative team. Library Wars: The Last Mission (図書館戦争-THE LAST MISSION-, Toshokan Senso -The Last Mission-) is the sequel that those who enjoyed the first film have been waiting for given the very obvious plot developments left unresolved at the previous instalment’s conclusion.

18 months later, Kasahara (Nana Eikura) is a fully fledged member of the Library Defence Force, but still hasn’t found the courage to confess her love to her long term crush and embittered commanding officer, Dojo (Junichi Okada). As in the first film, The Media Betterment Force maintains a strict censorship system intended to prevent “harmful” literature reaching “vulnerable” people through burning all suspect books before they can cause any damage. Luckily, the libraries system is there to rescue books before they meet such an unfortunate fate and operates the LDF to defend the right to read, by force if necessary.

Kasahara is an idealist, fully committed to the defence of literature. It is, therefore, a surprise when she is accused of being an accomplice to a spate of book burning within the library in which books criticising the libraries system are destroyed. Needless to say, Kasahara has been framed as part of a villainous plan orchestrated by fellow LDF officer Tezuka’s (Sota Fukushi) rogue older brother, Satoshi (Tori Matsuzaka). There is a conspiracy at foot, but it’s not quite the one everyone had assumed it to be.

In comparison with the first film, The Last Mission is much more action orientated with military matters taking up the vast majority of the run time. A large scale battle in which the LDF is tasked with guarding an extremely important book containing their own charter (i.e. a symbol of everything they stand for) but quickly discovers the Media Betterment Force is not going to pass up this opportunity to humiliate their rival, forms the action packed centrepiece of the film.

The theme this time round leans less towards combating censorship in itself, but stops to ask whether it’s worth continuing to fight even if you feel little progress is being made. The traitorous officer who helps to frame Kasahara does so because he’s disillusioned with the LDF and its constant water treading. The LDF is doing what it can, but it’s fighting to protect books – not change the system. This is a weakness Satoshi Tezuka is often able to exploit as the constant warfare and tit for tat exchanges have begun to wear heavy on many LDF officers who are half way to giving up and switching sides. Even a zealot like Kasahara is thrown into a moment of existential despair when prodded by Satoshi’s convincing arguments about her own obsolescence.

Satoshi rails against a world filled with evil words, but as the head of the LDF points out in quoting Heinrich Heine, the society that burns books will one day burn men. The LDF may not be able to break the system, but in providing access to information it can spread enlightenment and create a thirst for knowledge among the young which will one day produce the kind of social change that will lead to a better, fairer world.

As in Library Wars all of these ideas are background rather than the focus of the film which is, in essence, the ongoing non-romance between Kasahara and Dojo. Remaining firmly within the innocent shojo realm, the romantic resolution may seem overly subtle to some given the extended build up over both films but is ultimately satisfying in its cuteness. Library Wars: The Last Mission masks its absurd premise with a degree of silliness, always entirely self aware, but gets away with it through sincerity and good humour. Shinsuke Sato once again proves himself among the best directors of mainstream blockbusters in Japan improving on some of the faults of the first film whilst bringing the franchise to a suitably just conclusion.

Original trailer (No subtitles)

A Double Life (二重生活, Nijyuu Seikatsu ), the debut feature from director Yoshiyuki Kishi adapted from Mariko Koike’s novel, could easily be subtitled “a defence of stalking with indifference”. As a philosophical experiment in itself, it recasts us as the voyeur, watching her watching him, following our oblivious heroine as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the act of observance. Taking into account the constant watchfulness of modern society, A Double Life has some serious questions to ask not only of the nature of existence but of the increasing connectedness and its counterpart of isolation, the disconnect between the image and reality, and how much the hidden facets of people’s lives define their essential personality.

A Double Life (二重生活, Nijyuu Seikatsu ), the debut feature from director Yoshiyuki Kishi adapted from Mariko Koike’s novel, could easily be subtitled “a defence of stalking with indifference”. As a philosophical experiment in itself, it recasts us as the voyeur, watching her watching him, following our oblivious heroine as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the act of observance. Taking into account the constant watchfulness of modern society, A Double Life has some serious questions to ask not only of the nature of existence but of the increasing connectedness and its counterpart of isolation, the disconnect between the image and reality, and how much the hidden facets of people’s lives define their essential personality. Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.

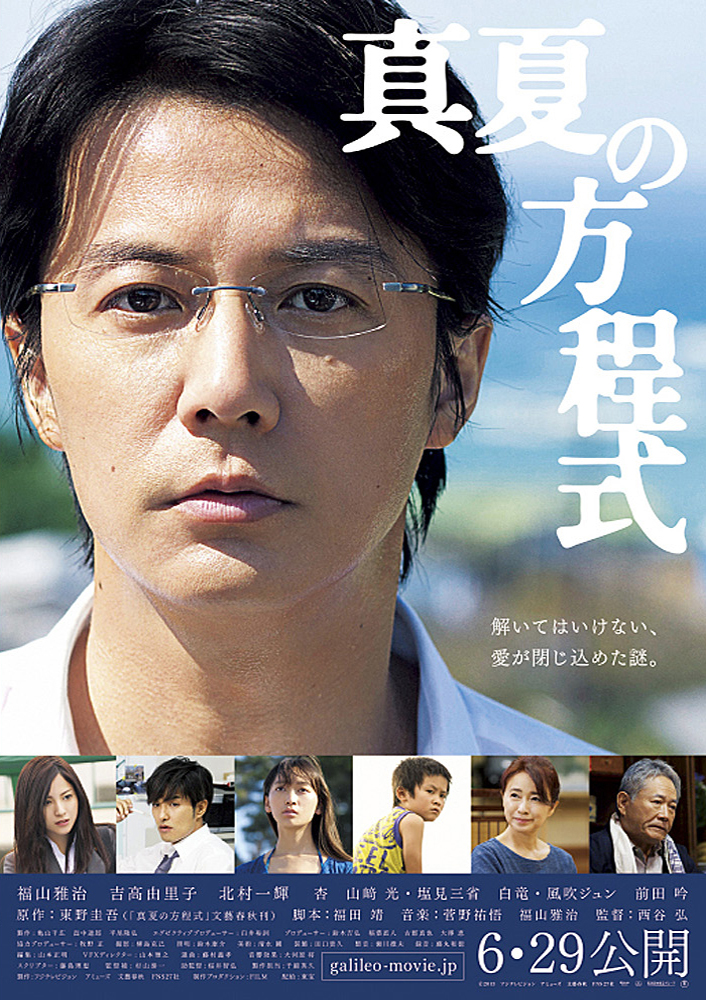

Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.