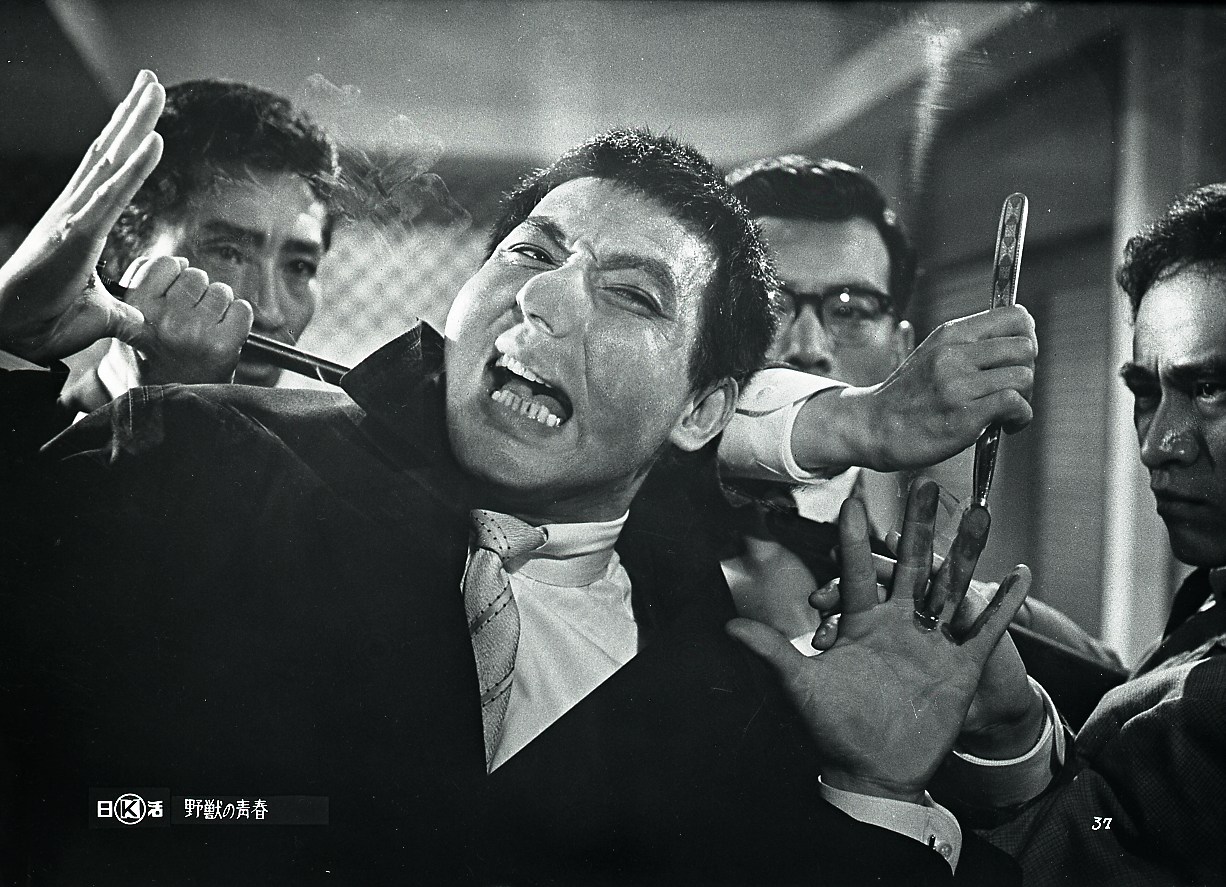

Time loop cinema has made a resurgence in Japan of late, but Shinji Araki’s Penalty Loop (ペナルティループ) is not quite what you’d assume it to be rather a meditation on the grieving process in a constant process of recycling rage and hurt day after day. When his girlfriend is murdered and her body is found dumped in a local lake, Jun becomes obsessed with the idea of revenge and turns up at the killer’s place of work where he poisons his morning coffee and then stabs him to death in his car before poetically dumping his corpse in the same lake where disposed of Yui’s (Rio Yamashita) body.

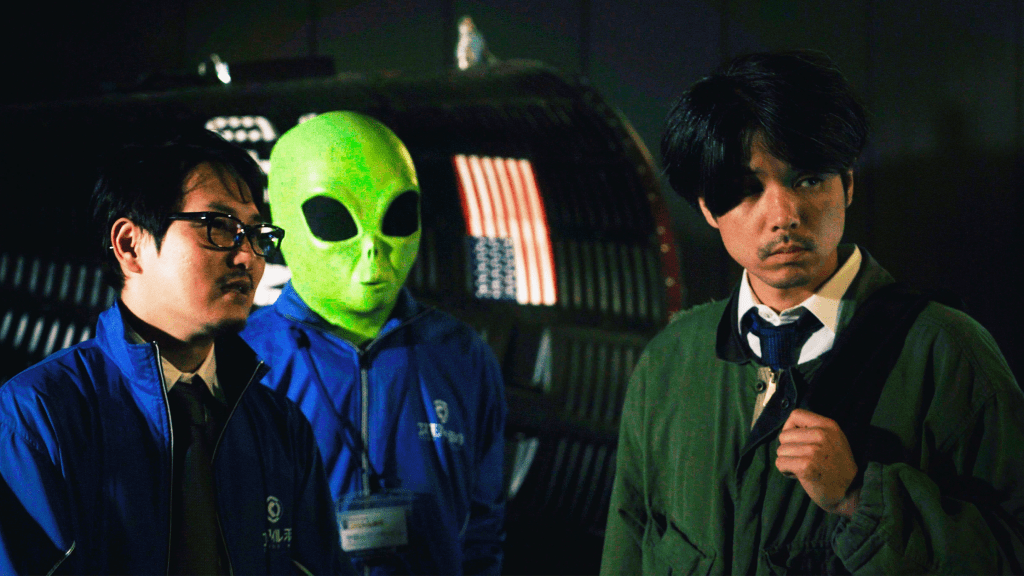

The weird thing is, that Jun (Ryuya Wakaba) wakes up the next day to discover it’s still 6th June and he has to do the same thing all over again. Rather than switching up his methods, he simply repeats the process but it turns out the Killer (Yusuke Iseya) is also aware they’re trapped in a loop and starts trying to avoid being killed. Before too long, the men have begun to trauma bond over their shared despair of being trapped in this constant cycle of retribution and become almost friends in an absurdist, existential meditation on the fallacies of justice and revenge. The killer and his indirect victim are locked in this cycle together and, the film seems to suggest, can only escape it through a process of healing and forgiveness rather than Jun’s futile attempts at revenge by killing the killer over and over again.

It is though somewhat perplexing that Jun never asks the Killer why he killed Yui and shows no real curiosity in his motives only asking him if he killed a lot of people. Yui also seems to have been mixed up in a concurrent conspiracy which the film does not go into or was in fact locked into her only cycle of despair and futily as the Killer suggests in volunteering that Yui wanted to die anyway, telling him that she had nothing to live for and was filled with emptiness. Of course, perhaps it’s simply the case that a kind of justice has already taken place in the “real” world and that Jun already knows why Yui was killed but simply wants a more personal kind of revenge to satisfy his hurt and anger, or that the Killer would not really be able to tell him much anyway because we can’t be sure he’s “real” or just a character existing for the purpose of Jun’s revenge no different from a dummy punch bag.

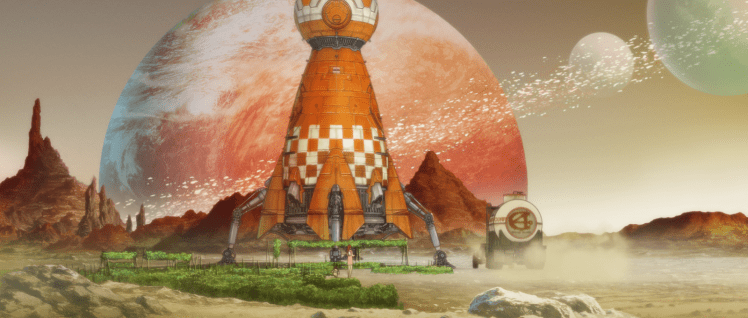

A strange, grinning man (Jin Daeyeon) is often seen observing the two men and later becomes irate on hearing Jun state that he no longer plans to kill the Killer but seems to have befriended him instead. His presence hints at a wider authoritarian presence that feeds off Jun’s negative emotions and forces him to continue vengeance long after he has tired of it. At this point, his killings become less violent. Rather than the poison and a knife, the bloody struggle in the car and the clinical process of bagging the body to be dumped in a lake, Jun uses a gun and the Killer patiently allows himself to be killed so that the cycle can continue. Further revelations suggest that the loop is less cosmic than commercial and Jun is constrained by a contract he signed for something that is supposed to be a kind of therapy the ethics of which would be very debatable, as would the offer of a secondary “rehab” programme on his completion of the process though how he, a man with no apparent income who lives in a room that already resembles a prison where he builds model houses that express the life he might have liked to give Yui, would be able to afford all this.

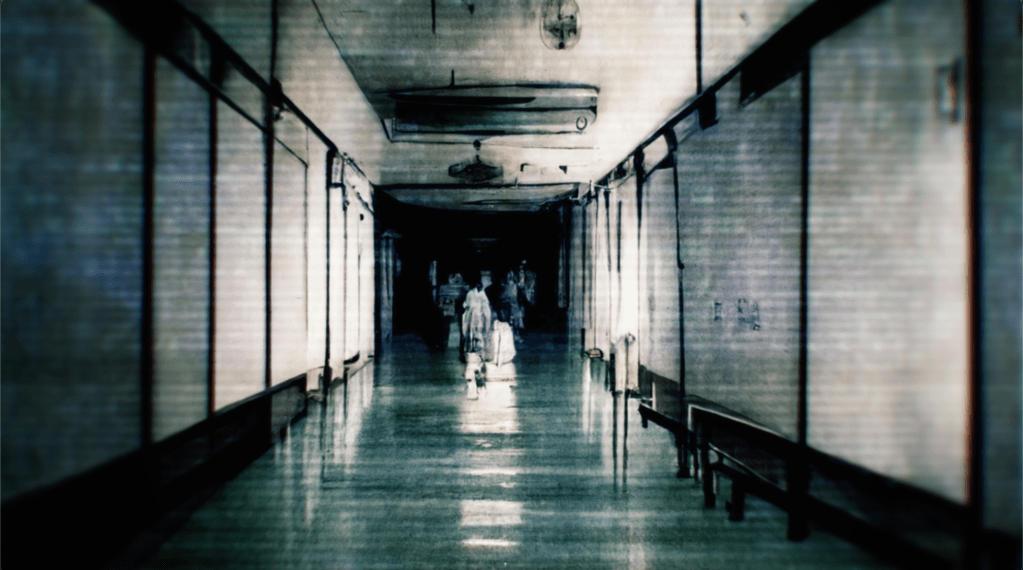

In any case, it’s true enough that Jun is imprisoned by his grief and powerlessness and his desire for vengeance is an attempt to free himself though in the end he can only do it by abandoning his rage and violence and finding empathy for the killer with whom he is trapped in this hellish cycle of grief and retribution. Araki lends his quest a dystopian air, taking place largely in some kind of hydroponic facility which otherwise exists only for the purposes of Jun’s revenge. Strangely quirky in its absurdist humour and bleak in some of its implications the film otherwise suggests that forgiveness is the only path out of grief for the cycle of vengeance will never really end.

Penalty Loop screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection