The figure of the “geisha” looms large in Japanese cinema, but all too often international perceptions of what a geisha is or should be are rooted in old fashioned orientalist ideas of exotic Eastern women somehow both refined and alluring. Most assume geisha is synonymous with high class prostitute and that the life of a geisha is not much different from any other sex worker save for the trappings of elegance which are in fact its USP. These assumptions are, however, not entirely accurate.

The figure of the “geisha” looms large in Japanese cinema, but all too often international perceptions of what a geisha is or should be are rooted in old fashioned orientalist ideas of exotic Eastern women somehow both refined and alluring. Most assume geisha is synonymous with high class prostitute and that the life of a geisha is not much different from any other sex worker save for the trappings of elegance which are in fact its USP. These assumptions are, however, not entirely accurate.

In order to tell the story of the modern day geisha, Ken Nishikawa steps in front of the camera to tell that of his own mother which is also in many ways, the story of 20th century Japan. Later known as Matsuchiyo, Nishikawa’s mother spent the pre-war years in Manchuria returning to a land in ruins shortly after the wartime defeat. In order to support her ailing mother, she became a geisha which is, as we will discover, an extraordinarily skilled and arcane profession entailing the mastery of a number of traditional arts from dance to shamisen.

As Matsuchiyo later puts it, it’s difficult for a foolish girl to become a geisha, but for an intelligent one it may be impossible. A flippant remark to be sure, but it hints at the true purpose of a geisha’s training which amounts to a gentle erasure of individual personality in order to play the role of the perfect woman from the point of view of each particular client. Somewhere between bartender and therapist, a geisha must listen patiently to the complaints of each of her companions as they pour out their souls over sake, laying bare the fears and worries with which they could never burden a wife (assuming they might want to). Nodding sympathetically, she must remain cheerful and supportive, never voicing her true feelings but only those the client has paid to hear. The business of a geisha isn’t selling sex but fantasy, an image of unconditional love which is entirely conditional on payment of the bill.

As far as bills go, being a geisha is an expensive business and so each must be careful to hook a patron who will support her ongoing career – paying for training, equipment, elaborate outfits and hairdressing, in return for preferential treatment and loyalty. Matsuchiyo, as young woman, fell in love with a handsome young man but he was poor and her family still had debts. Though they urged her to do what she thought best, Matsuchiyo made a sacrifice and gave up on love to continue her geisha training and provide for her family. She became the mistress of a wealthy elderly man and later the “shadow wife” of a younger one from a wealthy family who fathered her three children but had two more with a legal wife. On his death she received nothing and the children were not even allowed to go to their father’s funeral, such was the taboo nature of their existence from the point of view of their father’s family.

The children were also instructed not to tell people that their mother was a geisha, leaving them with a lingering feeling of shame regarding her profession even if Matsuchiyo herself has absolutely none. Becoming a geisha is hard, it takes skill and application not to mention an investment in time. These days there are few women who want to be one, possibly because of its associations with the sex trade, but also simply because times have changed. Before the war when poverty was at its height, it was “normal” to sell a daughter to a geisha house so she might feed her family. Thankfully, this was no longer (officially at least) possible in the post-war world, but when Matsuchiyo became a geisha there were many young women like her who did so to escape the kind of extreme poverty which is happily absent in the modern Japan. The geisha houses enjoyed a post-war boom in the Showa era but have been in rapid decline ever since, becoming perhaps a rarefied cultural icon while the regular foot traffic trots off to the decidedly more casual world of hostess bars.

Nishikawa narrates much of his mother’s story in English with occasional on screen graphics to aid in explanation before allowing her to tell some of it herself in subtitled Japanese. Though others might have lamented Matsuchiyo’s “hard life” filled with loss and heartbreak, she herself regrets nothing and continues to dedicate herself to the geisha craft as the president of Atami’s geisha guild, fostering the latest generation of younger women keen to carry on the geisha legacy in an ever modernising world. A fascinating insight into the tightly controlled dichotomies of a geisha’s life, Nishikawa’s personal documentary is also voyage through the changing society of post-war Japan through the eyes of those trained to observe and most particularly an old woman who survived it all with a smile.

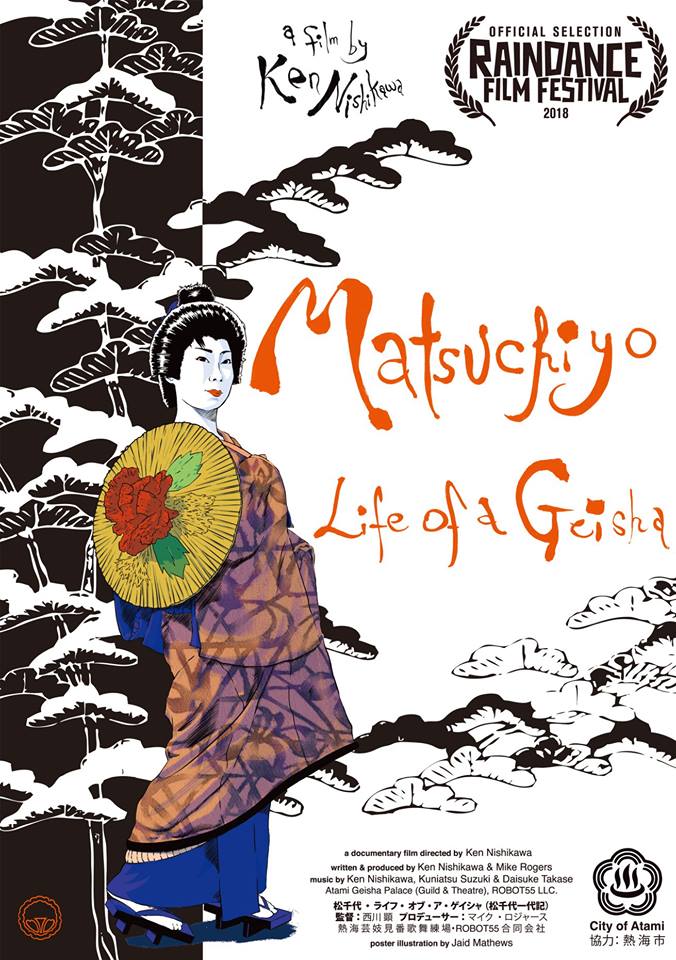

Matsuchiyo – Life of a Geisha (松千代一代記, Matsuchiyo Ichidaiki) was screened as part of the 2018 Raindance Film Festival.

Teaser trailer (English)

London’s

London’s  Shy schoolgirl Yo bonds with nurse Yayoi during a hospital stay. When she runs into her again some time later it’s under very different circumstances – Yayoi has become a sex worker. Trapped in an abusive home, Yo eventually decamps to Yayoi’s and demands to stay the summer, but Yayoi’s burgeoning romance threatens to destroy their fragile bond…

Shy schoolgirl Yo bonds with nurse Yayoi during a hospital stay. When she runs into her again some time later it’s under very different circumstances – Yayoi has become a sex worker. Trapped in an abusive home, Yo eventually decamps to Yayoi’s and demands to stay the summer, but Yayoi’s burgeoning romance threatens to destroy their fragile bond… Jun works in a hostess bar to save money to move to LA and pursue her dreams of becoming an actress, but having suffered violence from a customer and a romantic betrayal she decides to abandon the capital for her peaceful hometown. However, there are troubles to be found everywhere, not just in Tokyo….

Jun works in a hostess bar to save money to move to LA and pursue her dreams of becoming an actress, but having suffered violence from a customer and a romantic betrayal she decides to abandon the capital for her peaceful hometown. However, there are troubles to be found everywhere, not just in Tokyo…. A painter journeys into the mountains and falls in love with a local girl destined to become a mountain goddess.

A painter journeys into the mountains and falls in love with a local girl destined to become a mountain goddess. Yasuko suffers with a sleep disorder as well as manic depression and is looked after by her boyfriend Tsunaki (Masaki Suda) but their relationship is threatened by the resurfacing of Tsunaki’s ex.

Yasuko suffers with a sleep disorder as well as manic depression and is looked after by her boyfriend Tsunaki (Masaki Suda) but their relationship is threatened by the resurfacing of Tsunaki’s ex.

A Japanese real estate law requires landlords to inform prospective tenants if something unpleasant has previously happened in the property, but it doesn’t specify how long you need to keep that up. Thus some unscrupulous types have come up with a “room laundering” scheme in which they get people who don’t mind a little unpleasantness to move in for a short period of time to “purify” the living space. Miko is just such a woman and the arrangement suits her well enough, until, that is, she develops the ability to see ghosts.

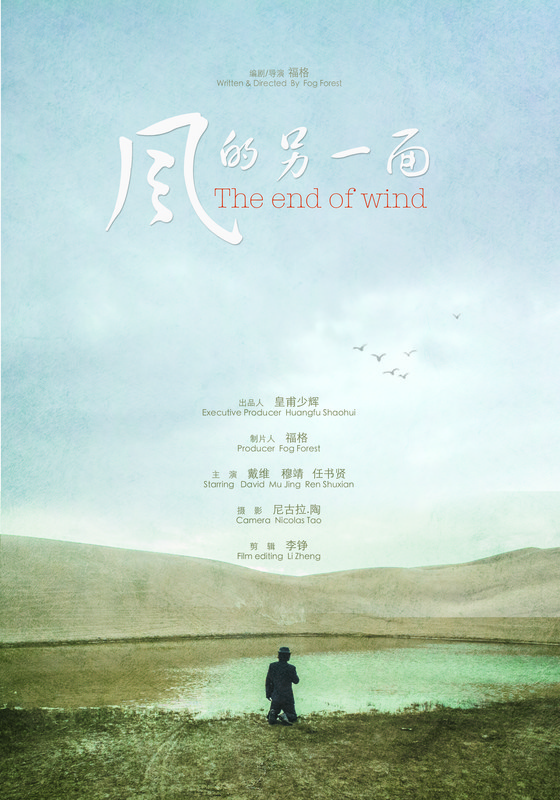

A Japanese real estate law requires landlords to inform prospective tenants if something unpleasant has previously happened in the property, but it doesn’t specify how long you need to keep that up. Thus some unscrupulous types have come up with a “room laundering” scheme in which they get people who don’t mind a little unpleasantness to move in for a short period of time to “purify” the living space. Miko is just such a woman and the arrangement suits her well enough, until, that is, she develops the ability to see ghosts.  A white collar worker in the middle of an existential crisis, an ex-con recently released from prison after being convicted of a crime he did not commit, and a refugee from North Korea seek release but find only more emptiness in the debut feature from Fog Forest.

A white collar worker in the middle of an existential crisis, an ex-con recently released from prison after being convicted of a crime he did not commit, and a refugee from North Korea seek release but find only more emptiness in the debut feature from Fog Forest.