Lupin and the gang find themselves in a race against time after being lured to a mysterious private island in Takeshi Koike’s latest instalment in the classic franchise, LUPIN THE IIIRD: The Movie – The Immortal Bloodline (LUPIN THE IIIRD THE MOVIE 不死身の血族, Fujimi no Ketsuzoku). A sequel to a series of specials, the film opens with a lengthy recap explaining that each member of Lupin’s team has been targeted for assassination and seen off their adversaries using their own particular skills. Now Lupin’s home has been destroyed taking most of his loot with it, so he too is in hot pursuit looking for answers about who might be trying to kill them and why, along with some treasure, of course.

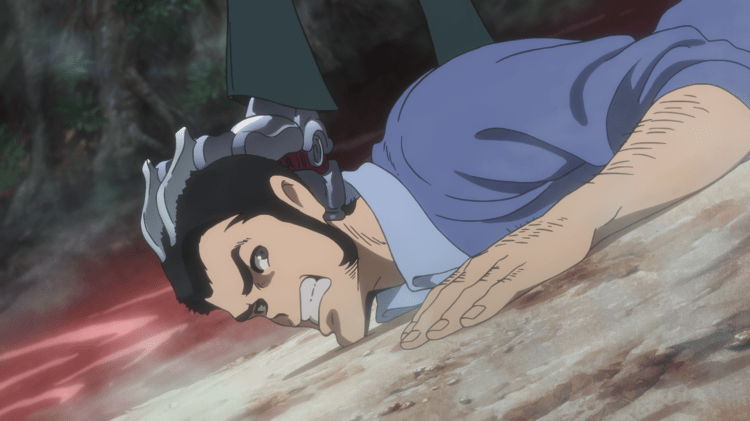

What he discovers, however, is that the island is a kind of graveyard for the unwanted. The place is full of mindless men in masks, the hitmen who didn’t make it reduced to animalistic predation. Disused military equipment scatters the landscape as if in reminder of mankind’s folly. But Lupin (voiced by Kanichi Kurita) is here because according to apparent mastermind Muom (Kataoka Ainosuke VI), he’s trash too and doesn’t belong in the new world Muom is trying to create by making the earth immortal. The air on the island is toxic to people like Lupin and unless he and his friends find a way off it within the next 24 hours, they’re destined to become zombie-like masked men too or else fade away into oblivion leaving not even a legacy behind them.

The war is then against a notion of obsolescence or the idea that a person can become somehow unnecessary. The gang were followed to the island by Zenigata (Koichi Yamadera) who is still trying to catch Lupin but ends up becoming trapped too. Lupin is obviously very necessary to Zenigata as without him he doesn’t really have a reason to exist. That’s one reason he ends up ironically teaming up with him, protecting Fujiko Mine (Miyuki Sawashiro) and breaking his own code to shoot some bad guys in an attempt to keep Lupin alive to face justice.

But as it turns out, Interpol might not be the best place to turn for back up as there’s some sort of blackout code on all things related to the island which is marked on no maps. Zenigata’s contact describes it as “sacred” and rather than sending the helicopter he asked for, explains everyone who sets foot on it will have to die because they know too much. As weird as Muom’s plans to make the earth immortal sound, it appears it’s locked into something bigger. All of which is quite good for Lupin who starts to realise there might not be much treasure here after all, but he’s found something more precious in a lead on even greater riches just waiting to be plundered.

This might be his way out of the purgatorial space of the island, the “hell for those burdened by karma” as Goemon (Daisuke Namikawa) describes it, in kicking back against Muom’s plans by identifying his nature and, quite literally, heading straight to the heart of the matter while reclaiming his identity as the gentleman thief from those who think he’s an unwelcome presence. Returning to the lair, he burns the history of himself and declares that life is a fiction to be enjoyed while immortality is a worthless gift that robs existence of its meaning. Separated on the island, the team must face their personal traumas alone before reuniting to try and figure out how to defeat their seemingly immortal captor and fight their way off the island before being consumed by its toxic gases.

The last in Koike’s Lupin cycle, the film is, in some ways, intended as a prequel to Mystery of Mamo, the very first Lupin anime released in 1978. As such it continues the style Koike has established in the series so far complete with kinetic action sequences and retro jazz score. Though this may seem like the end of the line for the gentleman thief, it is really just another beginning in returning the franchise to its point of origin. Lupin is, in a sense, reborn to steal back everything that was taken from him, with Zenigata hot on his heels and the world set to rights again, saved by his very particular brand of chaos.

LUPIN THE IIIRD: The Movie – The Immortal Bloodline opens in UK cinemas 21st February courtesy of Anime Limited.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Images: © MP / T

Kenji Miyazawa is one of the giants of modern Japanese literature. Studied in schools and beloved by children everywhere, Night on the Galactic Railroad has become a cultural touchstone but Miyazawa died from pneumonia at 37 years of age long before his work was widely appreciated. Night Train to the Stars (わが心の銀河鉄道 宮沢賢治物語, Waga Kokoro no Ginga Tetsudo: Miyazawa Kenji no Monogatari), commissioned to mark the centenary of Miyazawa’s birth, attempts to tell his story, set as it is against the backdrop of rising militarism.

Kenji Miyazawa is one of the giants of modern Japanese literature. Studied in schools and beloved by children everywhere, Night on the Galactic Railroad has become a cultural touchstone but Miyazawa died from pneumonia at 37 years of age long before his work was widely appreciated. Night Train to the Stars (わが心の銀河鉄道 宮沢賢治物語, Waga Kokoro no Ginga Tetsudo: Miyazawa Kenji no Monogatari), commissioned to mark the centenary of Miyazawa’s birth, attempts to tell his story, set as it is against the backdrop of rising militarism.