Do our memories just vanish when we die? The murderous professor at the centre of Takashi Shimizu’s Reincarnation (輪廻, Rinne) was apparently obsessed with just this question, along with that of where we come from when we’re born and where we go when our corporeal lives have ended. But there’s a curious irony at the film’s centre in the ways in which we consciously or otherwise seek to recreate the past that suggests we are locked into a karmic cycle even while within the mortal realm.

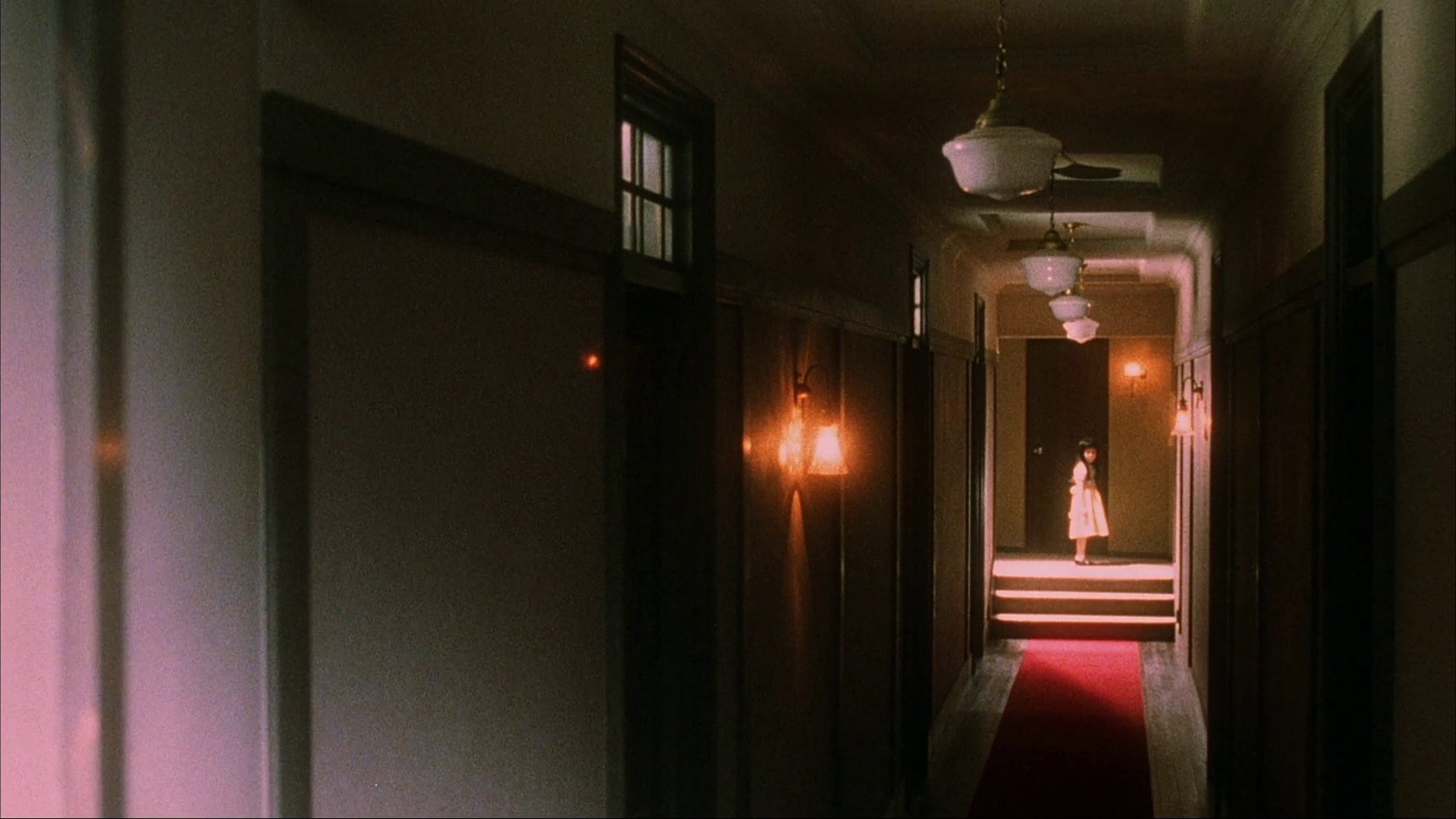

The most obvious sign of that is the director Matsumoto’s (Kippei Shina) obsession with the grisly murder case that took place 35 years previously. He means to recreate it literally by building an exact replica of the hotel where it took place, only he intends to refocus the tale on the victims, leaving the killer a mysterious force in the shadows. It’s clear that this traumatic incident has left a mark on the wider world, not only in its lingering mystery but the darkness with which it is enveloped, while Matsumoto seeks to exploit it either for commercial gain or reasons of his art. We’re told that, perhaps like Shimizu himself, Matsumoto is known for a particular kind of filmmaking, in his case one involving copious levels of blood and gore.

He’s drawn to aspiring actress Nagisa (Yuka) for unclear reasons, though her affinity for the material connects her intensely with this story as she too finds herself haunted by the figure of a little girl in a yellow dress carrying a huge and actually quite creepy doll. There is a sense that everyone is being drawn back here into the nexus of this trauma to play it out again, ostensibly for entertainment. Another actress at the audition, Yuka (Marika Matsumoto), seemingly kills her chances by bringing up that she has memories of being murdered in a past life and thinks that she might be able to put them to rest by acting them out. She too is connected to the hotel and possibly a reincarnation of a woman who was hanged during the incident, which is why she bears an eerie noose mark around her neck.

Yuka is more literally scarred by a traumatic legacy, while those around her are merely curious or confused. Yayoi (Karina) has recurring dreams of the hotel which her parents can’t explain, leading to the suspicion that she too is a reincarnation of someone who died there, though all of the women were born long after the incident took place. Her professor at university (Kiyoshi Kurosawa) is cautious when it comes to the idea of the authenticity of memory. He teaches them about the concept of “cryptomnesia”, when a forgotten memory is recalled but not recognised as such, leading to accidental incidents of plagiarism in which the subject assumes their idea is original rather than a regurgitation of something they saw or heard long before but no longer “remember”. There is also, of course, the reality that many of our “memories” are effectively constructed from things others have told us of our childhoods that we don’t actually recall but are a result of our brain trying to fill in the blanks. Perhaps this might explain Yayoi’s dreams, that she came across the famous case at some point when she was too young to understand it and it’s implanted herself in her subconscious as an unanswered question.

Which is to say that perhaps it’s the memories that are being reincarnated in someone else’s head as much as it’s the disused hotel that’s become a place of trauma haunted by past violence and now inhabited by the pale-faced ghosts of those who died unjustly. The events themselves are constantly repeating just as the moments exist contemporaneously rather than in a linear cycle. Indeed, they are eventually preserved both through the film shot by the killer, witnessed as a document, and the film that Matsumoto was making, enjoyed as entertainment, but ultimately in Nagisa’s head where all concerned can indeed be “together forever” if now confined to eternal rest in the space of memory.

Trailer (no subtitles)