Living a life without regrets is easier said than done. The protagonists of Michihito Fujii’s The Parades (パレード, Parade) each have unfinished business that prevents them moving on from this world, but what they discover is an unexpected sense of solidarity among similarly lost souls as they try to lay themselves to rest. After all, all they can do now is observe and reflect while helping others like them with their own lingering doubts and regrets.

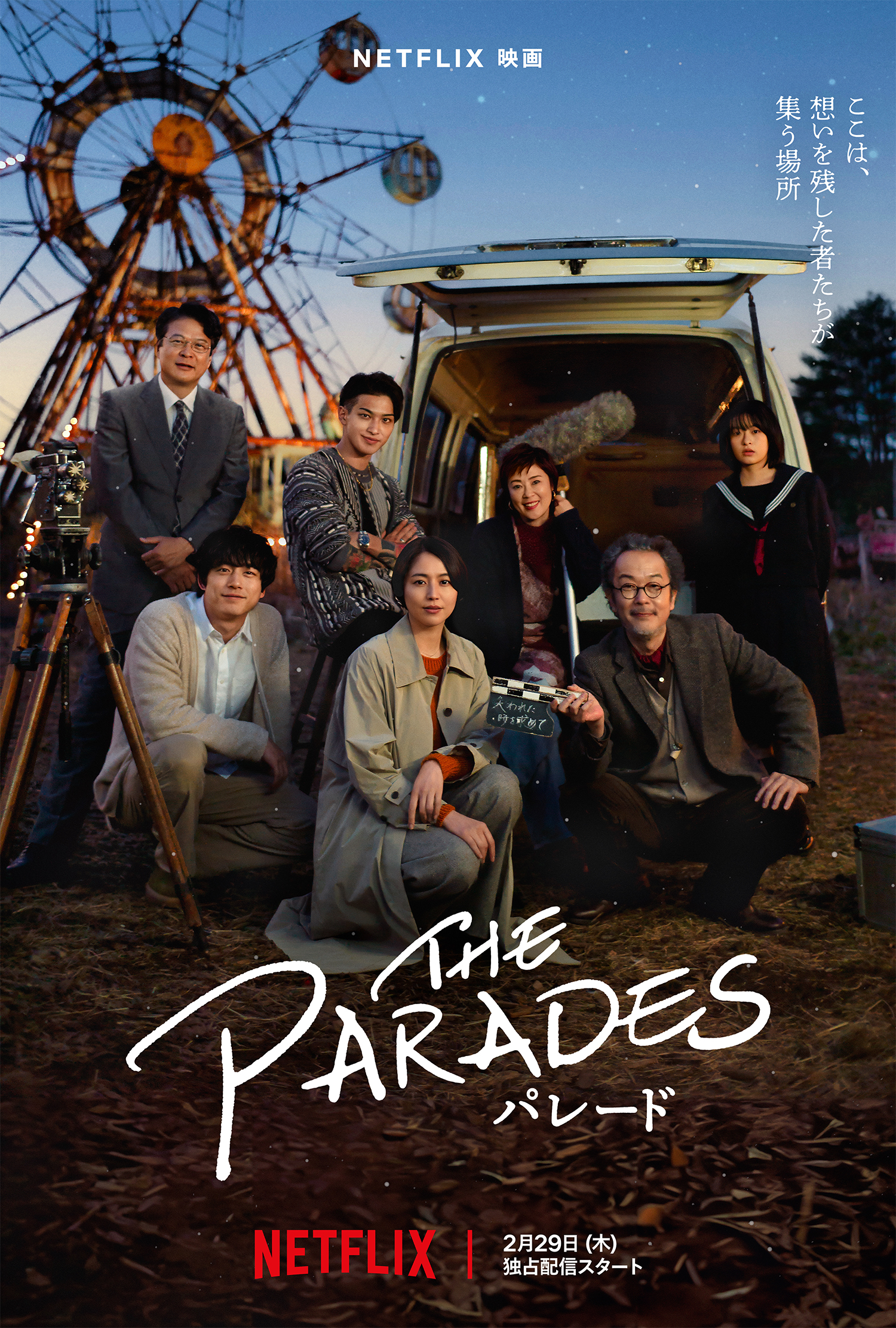

Drawing inspiration from the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, Fujii first introduces us to Minako (Masami Nagasawa). A 35-year-old single mother, she wakes up on a beach and frantically looks for her seven-year-old son Ryo (Haru Iwakawa) little realising that the reason no one seems to be able to hear or react to her is because she’s already dead. Picked up by fellow ghost Akira (Kentaro Sakaguchi), she’s taken to a disused fairground that doubles as a hub for wandering souls. Though it takes her a while to accept her new situation, she gradually bonds with others at the camp each of whom have their own unfinished business which isn’t all that different from her own in that they mostly want to be sure the people they left behind will be alright.

The film takes its name from the monthly processions in which wandering souls meet by lantern light to look for their missing people together. This sense of solidarity and empathy seems to echo the best of humanity along with a melancholy longing. There appears to be little rancour in this afterlife, a yakuza who was killed in a gang war simply feels sorry for his father and so guilty about the girlfriend he left behind that he’s been afraid to face her for the last seven years, and a high school girl who took her own life because of bullying first thinks her unfinished business is vengeance on the bullies but later accepts is actually a desire to apologise to her best friend who then had to take the brunt of the bullies’ cruelty on her own.

What the film seems to say is that we should have more of this fellow feeling in life. Former film producer Michael (Lily Franky) constantly references his days as a student protestor remarking that they might not have amounted to very much but at least they had unity. His regret is less his failed revolution than a moment of emotional cowardice that saw the woman he loved marry someone else instead. Constant references to the end of Casablanca echo their plight as if Maiko (Yuina Kuroshima / Hana Kino) married Sasaki (Ayumu Nakajima / Hiroshi Tachi) for the good of the revolution though she really loved Michael who unlike Rick just walked out on it because in the end he wasn’t brave enough to risk the consequences of its success or failure.

The world building may not always be consistent and the rules of this universe appear unclear. It seems that in general the ghosts don’t linger long. Even the heavenly liaison Tanaka (Tetsushi Tanaka) appears to have been dead not longer than 40 years with Michael seemingly the only other long-stayer with the others’ deaths fairly recent. In general they are only really waiting for themselves or others, wanting to make sure that their loved ones will be alright in their absence even though there’s nothing more they can do for them now other than observe. Though they can walk through this world and interact with physical objects, their presence is otherwise invisible unless the person they wish to contact happens to be in an altered state. To this extent, the resolution may seem like a bit of a cop-out but does lend an additional poignancy and imply that these lessons learned in limbo can still be taken into the mortal realm creating additional empathy and solidarity among the living so that they may be able to live their lives freely and fully perhaps not entirely without regrets but at least with fewer of those that would prevent them from moving on when their time comes. But even if they find themselves trapped in limbo, they’ll hopefully find others like themselves and a gentle sense of hopefulness about what’s to come even as they prepare to leave this world.

Trailer (English subtitles)