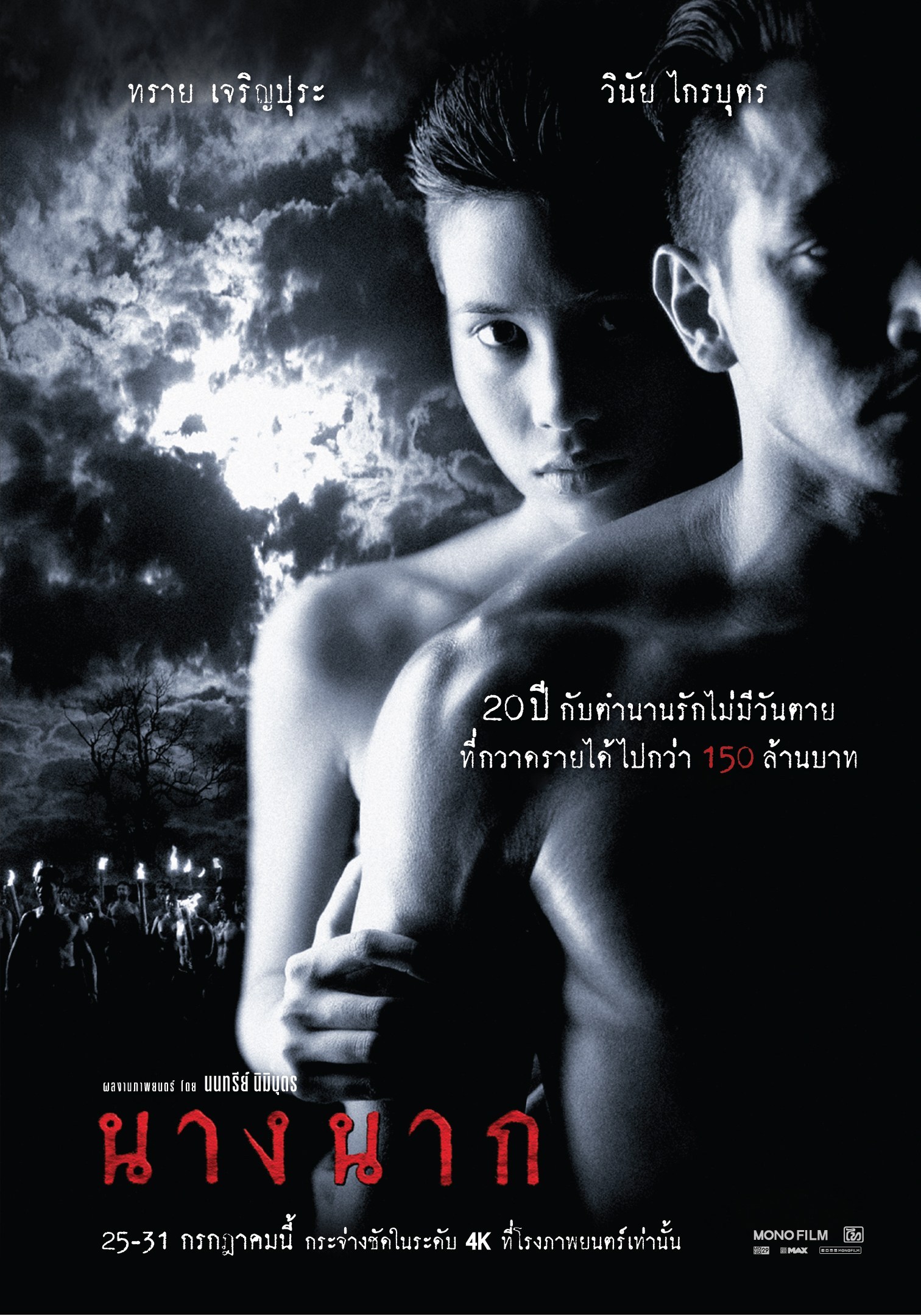

If you suddenly discover your spouse is a member of the undead, do you really have to break up with them or is it alright to go on living with a ghost? The conventional wisdom in Banjong Pisanthanakun’s horror comedy take on the classic folktale Mae Nak Phra Khanong, Pee Mak (พี่มาก..พระโขนง), is that the dead cannot live with the living, but perhaps love really is strong enough to overcome death itself and living without the person who means most to you really might be more frightening than living with an all-powerful supernatural entity.

In any case, much of the comedy revolves around the desperate attempts of Pee Mak’s friendship group to make him realise that wife, Nak (Davika Hoorne), is a ghost. The men had all been away at the war and have now returned but the village seems different and the villagers are all avoiding Pee Mak. Gradually, it dawns on them that Nak actually died due to complications from a miscarriage after going into labour alone at home given Pee Mak’s absence. But Pee Mak himself remains unaware of this fact, or so it seems, and refuses to listen to his friend’s attempts to convince him which are also frustrated by their fear of Nak and the worry that she might curse them if they reveal her secret.

The four friends are each played by the same actors and have the same character names as those in the shorts Banjong Pisanthanakun directed for 4Bia and Phobia 2, and as in those two films there is a degree of confusion about who is and isn’t a ghost. On their return, the men are passed by a ferryman who is returning the bodies of dead soldiers to their families explaining that the graveyards are all full. This of course hints at the destructive costs of the war and haunted quality of the depleted village to which not all men have returned, but also leaves the door open to wondering if the five of them are not already dead themselves and have returned home only in spirit without realising. Pee Mak, after all, sustains a serious injury from which he miraculously recovers driven only love and the intense desire to return home to his wife and the baby he’s never met who must by now have been born.

Meanwhile, Nak tells Pee Mak that the rumours of her death are greatly exaggerated and mostly put about by a local man, Ping, who had been harassing her while Pee Mak was away at the war and was upset by her rejection. Ping then later also accuses Nak of killing his mother after she drunkenly told Pee Mak about Nak being a ghost, but in general the villagers only avoid Nak until one rather late intervention rather than try to exorcise her spirit. Nevertheless ghost or not, it does not actually appear that Nak is particularly dangerous. She does not drain Pee Mak’s life force nor randomly attack other people and at most only seems to glare intensely at his friends who might just be annoying in far more ordinary ways especially as one of them seems have developed a crush her.

Which is all to say, is it really so wrong for Pee Mak to enjoy a happy family life with his ghost wife who may have developed a set of really useful skills such as super-stretchy arms and the ability to hang upside down? Banjong Pisanthanakun constantly wrong-foots us, suggesting that perhaps everyone’s already dead, or maybe no one is, while eventually coming down on the side of the power of love to overcome death itself. Despite the film’s setting in the distant past, he throws in a constant stream of anachronistic pop culture references that might suggest this is all taking place in some kind of universal time bubble but also lends to the sense of absurdity in what is really a kind of existential farce as the gang attempt to figure out who’s alive and who’s a ghost before eventually realising that it might not really matter. Dead or alive, it seems like life is about just being silly with your friends free from the folly of war, which is surely a message many can firmly get behind.

Trailer (English subtitles)