Jung Byung-gil’s Confession of Murder may have been a slightly ridiculous revenge drama, but it had at its heart the necessity of dealing with the traumatic past head on in order to bring an end to a cycle of pain and destruction. Yu Irie retools Jung’s tale of a haunted policeman for a wider examination of the legacy of internalised impotence in the face of unavoidable mass violence – in this case the traumatic year of 1995 marked not only by the devastating Kobe earthquake but also by Japan’s only exposure to an act of large scale terrorism. Persistent feelings of powerlessness and nihilistic despair conspire to push fragile minds towards violence as a misguided kind of revenge against their own sense of insignificance but when a killer, safe in the knowledge that they are immune from prosecution after surviving the statute of limitations for their crimes, attempts to profit from their unusual status, what should a society do?

Jung Byung-gil’s Confession of Murder may have been a slightly ridiculous revenge drama, but it had at its heart the necessity of dealing with the traumatic past head on in order to bring an end to a cycle of pain and destruction. Yu Irie retools Jung’s tale of a haunted policeman for a wider examination of the legacy of internalised impotence in the face of unavoidable mass violence – in this case the traumatic year of 1995 marked not only by the devastating Kobe earthquake but also by Japan’s only exposure to an act of large scale terrorism. Persistent feelings of powerlessness and nihilistic despair conspire to push fragile minds towards violence as a misguided kind of revenge against their own sense of insignificance but when a killer, safe in the knowledge that they are immune from prosecution after surviving the statute of limitations for their crimes, attempts to profit from their unusual status, what should a society do?

22 years ago, in early 1995, a spate of mysterious stranglings rocked an already anxious Tokyo. In 2010, Japan removed the statute of limitations on capital crimes such as serial killings, mass killings, child killings, and acts of terror, which had previously stood at 15 years, leaving the perpetrator free of the threat of prosecution by only a matter of seconds. Then, all of a sudden, a book is published claiming to be written by the murderer himself as piece of confessional literature. Sonezaki (Tatsuya Fujiwara), revealing himself as the book’s author at a high profile media event, becomes a pop-culture phenomenon while the victims’ surviving families, and the detective who was in charge of the original case, Makimura (Hideaki Ito), incur only more suffering.

Unlike Jung’s version, Irie avoids action for tense cerebral drama though he maintains the outrageous nature of the original and even adds an additional layer of intrigue to the already loaded narrative. Whereas police in Korean films are universally corrupt, violent, or bumbling, Japanese cops are usually heroes even if occasionally frustrated by the bureaucracy of their organisation or by prevalent social taboos. Makimura falls into hero cop territory as he becomes a defender of the wronged whilst sticking steadfastly to the letter of the law in insisting that the killer be caught and brought to justice by the proper means rather than sinking to his level with a dose of mob justice.

Justice is, however, hard to come by now that, legally speaking, the killer’s crimes are an irrelevance. Sonezaki can literally go on TV and confess and nothing can be done. The media, however, have other ideas. The Japanese press has often been criticised for its toothlessness and tendency towards self-censorship, but maverick newscaster and former war correspondent Sendo (Toru Nakamura) is determined to make trial by media a more positive move than it sounds. He invites Sonezaki on live TV to discuss his book, claiming that it’s the opportunity to get to the truth rather than the viewing figures which has spurred his decision, but many of his colleagues remain skeptical of allowing a self-confessed murderer to peddle his macabre memoirs on what they would like to believe is a respectable news outlet.

The killer forces the loved ones of his victims to watch while he goes about his bloody business, making them feel as powerless as he once did while he remains ascendent and all powerful. It is these feelings of powerlessness and ever present unseen threats born of extensive personal or national traumas which are responsible for producing such heinous crimes and by turns leave behind them only more dark and destructive emotions in the desire for violence returned as revenge. Focussing in more tightly on the despair and survivors guilt which plagues those left behind, Irie opts for a different kind of darkness to his Korean counterpart but refuses to venture so far into it, avowing that the law deserves respect and will ultimately serve the justice all so desperately need. Irie’s artier approach, shifting to grainier 16:9 for the ‘90s sequences, mixing in soundscapes of confusing distortion and TV news stock footage, often works against the outrageous quality of the convoluted narrative and its increasingly over the top revelations, but nevertheless he manages to add something to the Korean original in his instance on violence as sickness spread by fear which can only be cured through the calm and dispassionate application of the law.

Screened as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2018.

Screening again:

- Showroom Cinema – 22 March 2018

- Broadway – 23 March 2018

- Firstsite – 24 March 2018

- Midlands Arts Centre – 24 March 2018

- Queen’s Film Theatre – 25 March 2018

Original trailer (English subtitles)

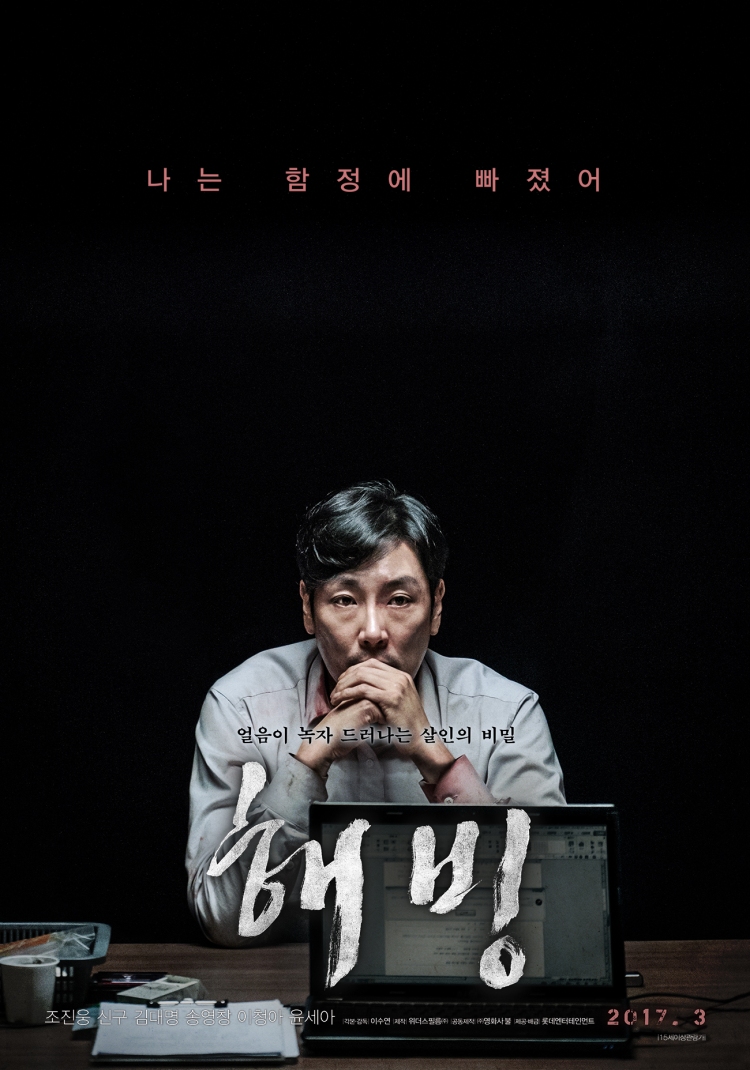

If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects.

If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects.