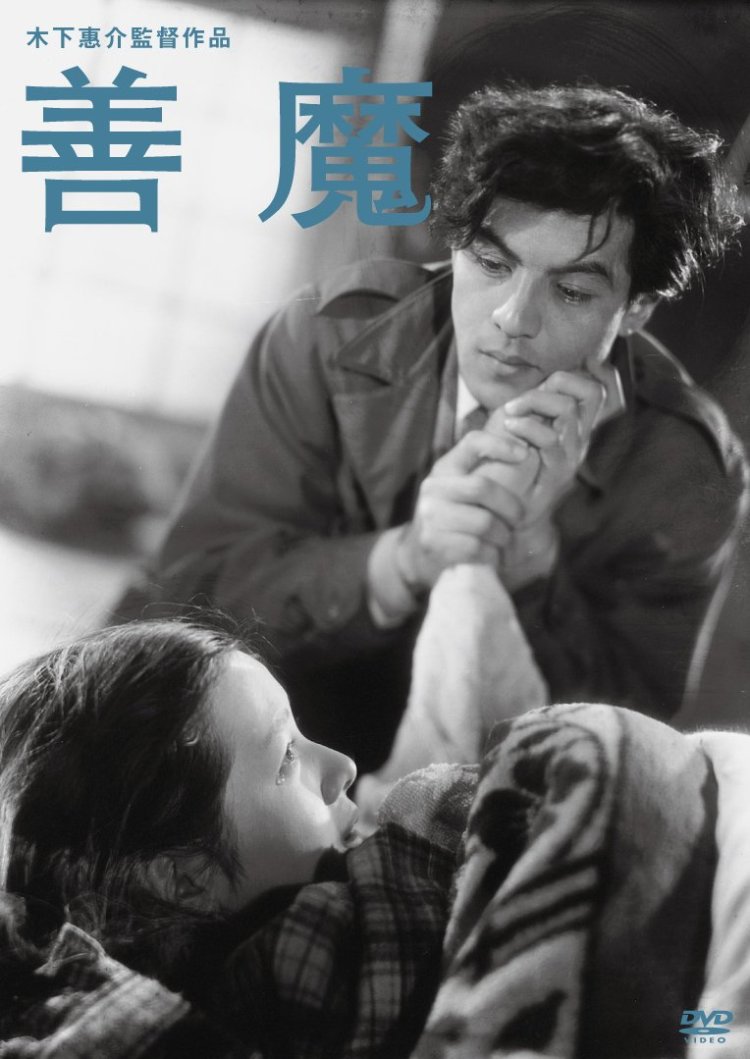

Although one of the more prominent names in post-war cinema, the work of Keisuke Kinoshita has often been out of fashion, derided for its sentimental naivety. It is true to say that Kinoshita values heroes whose essential goodness improves the world around them though that is not to say that he is entirely without sympathy for the conflicted or imperfect even if his equanimity begins to waver with age. 1951’s The Good Fairy (善魔, Zemma), however, working from a script penned not by himself but Kogo Noda and adapted from the novel by Kunio Kishida, seems to turn his life philosophy on its head, wondering whether the tyranny of puritanical goodness is an evil in itself or merely the best weapon against it.

Although one of the more prominent names in post-war cinema, the work of Keisuke Kinoshita has often been out of fashion, derided for its sentimental naivety. It is true to say that Kinoshita values heroes whose essential goodness improves the world around them though that is not to say that he is entirely without sympathy for the conflicted or imperfect even if his equanimity begins to waver with age. 1951’s The Good Fairy (善魔, Zemma), however, working from a script penned not by himself but Kogo Noda and adapted from the novel by Kunio Kishida, seems to turn his life philosophy on its head, wondering whether the tyranny of puritanical goodness is an evil in itself or merely the best weapon against it.

After beginning with a hellish, ominous title sequence set against the flames, the film opens with newspaper editor Nakanuma (Masayuki Mori) getting a hot tip regarding a politician’s wife who seems to have mysteriously disappeared. He hands the assignment to rookie reporter Rentaro Mikuni (played by the actor Rentaro Mikuni who subsequently took his stage name from this his debut role) who specialises in political corruption. Mikuni doesn’t like the assignment. He thinks it’s unethical and whatever happens between a man and his wife is no one’s business, but ends up going to see the politician, Kitaura (Koreya Senda), anyway and instantly dislikes him. Mildly worried by Kitaura’s lack of concern over his wife’s sudden absence, Mikuni stays on the case and visits the wife’s father (Chishu Ryu) up in the mountains where he also meets her sister, Mikako (Yoko Katsuragi), who eventually leads him to the woman herself, Itsuko (Chikage Awashima), who has taken refuge with a friend after becoming disillusioned with her husband’s “vulgar” pursuit of success at the continuing cost of human decency.

To pull back for a second, in any other Kinoshita film, Itsuko would be among the heroes in standing up against her husband’s corrupting influences, but for reasons which will later be explained she lingers on the borders of righteousness owing to having made a mistaken choice in her youth which was, in many ways, defined by the times in which she lived. Nukanuma had not been entirely honest with Mikuni in that he had known and secretly been in love with Itsuko when they were both students but he was poor and diffident and so he never declared himself, his only attempt to hint as his feelings either tragically or wilfully misunderstood. Where Itsuko, who married for money and status as a young woman was expected to do in the pre-war society, has mellowed with age and gained compassionate morality, Nakanuma who became a reporter to fight for justice against the background of fascist oppression has become cynical and selfish. Never having quite forgotten Itsuko, he has been in a casual relationship with a young actress, Suzue (Toshiko Kobayashi), for the last two years never realising that she has really fallen in love with him.

Thinking back on his college relationship with Itsuko, Nakanuma remembers talking with her about unsuccessful romances, that if a man tries his best to make a woman happy but isn’t able to then it must be because she doesn’t love him. Itsuko agrees, adding that men never seem to know what makes a woman happy in love but that friendship is a different matter. She says something similar when she tells him she’s getting married but doesn’t want to lose his friendship, and when he begins floating the idea of marriage hinting that he wants to marry her but perhaps giving the mistaken impression that there’s someone else in stating that it’s sad when a friend marries because the relationship with never be the same again and knowing that he intends to marry she now treasures their friendship even more. In a sense, Nakanuma thinks of Suzue as a “friend” with whom he occasionally sleeps, believing that their relationship is only ever liminal and temporary but mutually beneficial and capable of continuing even if the sexual component had to end.

Having failed once in love, Nakanuma is resolved not to do so again and determined to fight to win Itsuko rather than lose her through cowardice, but to do so he will cruelly wound Suzue who has treated him with nothing other than tenderness. By this time, Mikuni has fallen in chaste, innocent love with Mikako who reminds him of the parts of himself he feels are being erased by his compromising job as part of the mass media machine. Mikuni’s terrifying “goodness” is largely a positive quality which leads him to fight for justice against oppression even within his own organisation but his love for the saintly Mikako only intensifies his moral purity and threatens not only to turn him into an insufferable prig but to create in him a new oppressor, spreading guilt and unhappiness like the self-righteous hero of an Ibsen play.

Early on, following their mild disagreement about journalistic ethics, Mikuni and Nakanuma have dinner together over which they debate the power of the press to bring about social change and hold power to account. Nakanuma says he’s become cynical because hating injustice isn’t enough and there’s nothing that the individual can do against an oppressive system. What he’s telling Mikuni is that he used to be like him, but time has taught him righteousness is not an effective weapon against entrenched social privilege. He recounts a dark story from a Buddhist monk who told him that good can never win over evil because it isn’t strong enough, only evil is strong enough to fight evil and so in order to counter it you will need to affect its weapons. Later, crazed by grief and exhaustion, Mikuni’s “goodness” seems to pulse out of him with ominous supernatural force as he takes Nakanuma to task for his callous treatment of Suzue only for he and Itsuko to come to the conclusion that they’ve heard the voice of “evil” and are now condemned by their past choices to lives of morally pure unhappiness.

This central conundrum seems to contradict Kinoshita’s otherwise open philosophies in its unwelcome rigidity which says that there are no second chances and no possibility of ever moving on from the past with positivity. Itsuko made the “wrong” choice when she was young in choosing to marry for material gain, but she was only making the choice her society expected her to make in the absence of other options – it wasn’t as if she had any reason to wait around for Nakanuma whose regret over his romantic cowardice has made him cold and bitter. She realised her mistake too late and resolved to correct it, but the “Good Fairy” won’t let her, it says she has to pay (for the crimes of an oppressive society) by sacrificing again her chance of happiness in the full knowledge of all she’s giving up. Kinoshita’s films advocate the right to love by will, free of oppressive social codes or obligations but Itsuko is denied a romantic resolution despite having “reformed” herself and made consistently “correct” choices since discovering her husband’s “fraud”. She is denied this largely because of Nakunuma’s failing in being unkind to one who loved him, which is, in a round about way, still her fault for not having realised he loved her and deciding to marry him instead. In fact, the only one who seems to get off scot-free is Kitaura whose fraudulent activities will be covered up on the condition he consent to Itsuko’s divorce petition and sets her fully “free” so she can be fully burdened by the weight of her romantic sacrifice.

In the end, it’s difficult to see a positive outcome which could emerge from all this unhappiness which seems primed only to spread and reproduce itself with potentially disastrous consequences. Mikuni’s purity has become puritanical, unforgiving and rigid, condemning all to a hellish misery from which there can be no escape. The cure is worse than the disease. No one could live like this, and no one should. Goodness, tempered by compassion and understanding, might not be enough to fight the darkness all alone but it might be better to live in the half-light than in the hellish flickering of the fires of righteousness.

Title sequence and opening scene (no subtitles)

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –  Shochiku was doing pretty well in 1951. Accordingly they could afford to splash out a little in their 30th anniversary year in commissioning the first ever full colour film to be shot in Japan, Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る, Carmen Kokyou ni Kaeru). For this landmark project they chose trusted director Keisuke Kinoshita and opted to use the home grown Fujicolor which has a much more saturated look than the film stocks favoured by overseas studios or those which would become more common in Japan such as Eastman Colour or Agfa. Fujicolour also had a lot of optimum condition requirements including the necessity of shooting outdoors, and so we find ourselves visiting a picturesque mountain village along with a showgirl runaway on her first visit home hoping to show off what a success she’s made for herself in the city.

Shochiku was doing pretty well in 1951. Accordingly they could afford to splash out a little in their 30th anniversary year in commissioning the first ever full colour film to be shot in Japan, Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る, Carmen Kokyou ni Kaeru). For this landmark project they chose trusted director Keisuke Kinoshita and opted to use the home grown Fujicolor which has a much more saturated look than the film stocks favoured by overseas studios or those which would become more common in Japan such as Eastman Colour or Agfa. Fujicolour also had a lot of optimum condition requirements including the necessity of shooting outdoors, and so we find ourselves visiting a picturesque mountain village along with a showgirl runaway on her first visit home hoping to show off what a success she’s made for herself in the city. There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.

There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.