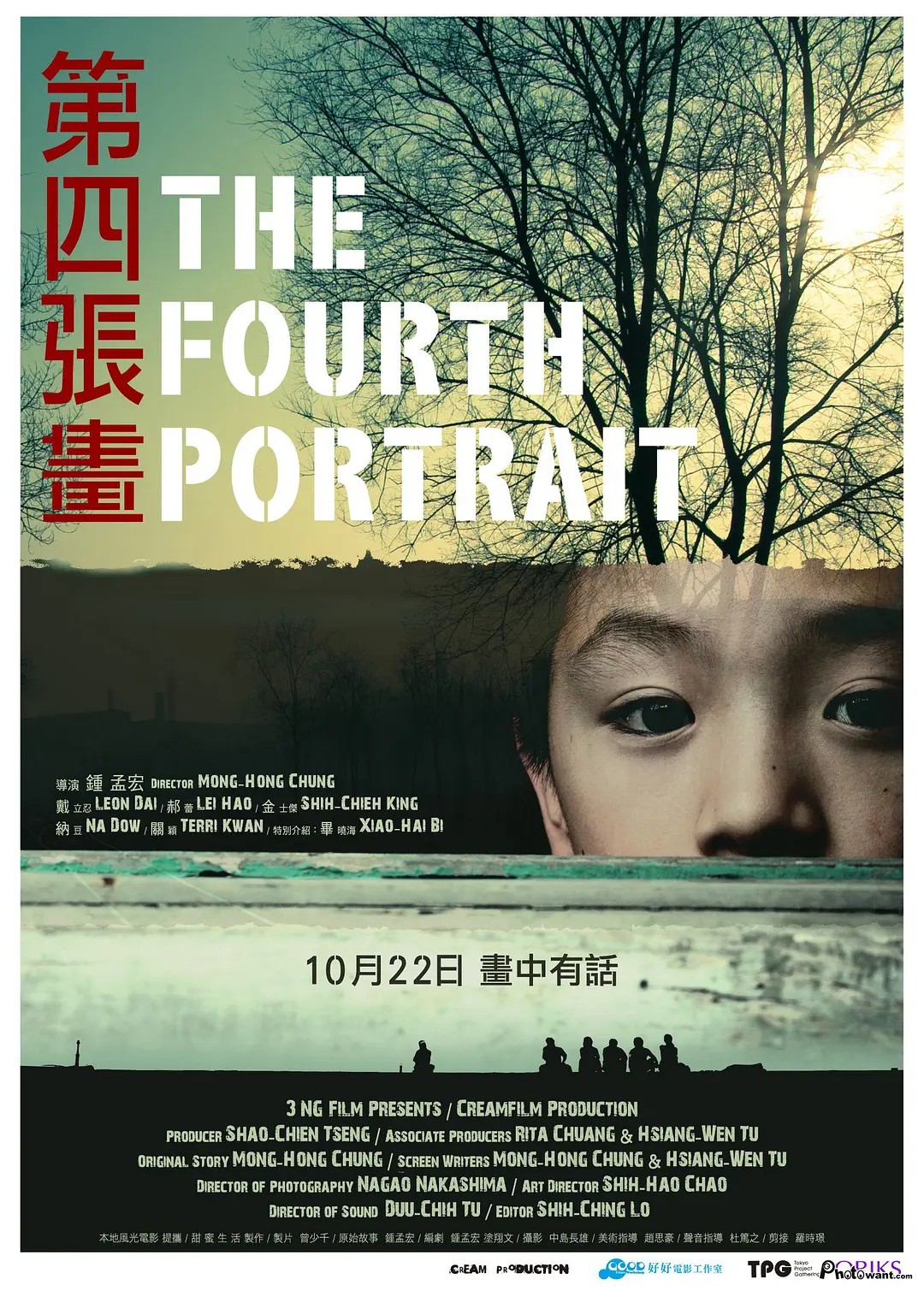

A young boy struggles to forge his own identity while lost amid the legacy of perpetual displacement in Chung Mong-Hong’s whimsical coming-of-age drama The Fourth Portrait (第四張畫). As the title implies, Chung structures his tale around four images as the boy looks for guidance through each of his relationships but perhaps finally discovers only that he is on his own and has only himself for protection yet must find the courage to try and escape even if it causes him pain.

At 10 years old, young Xiang (Bi Xiao-Hai) is impossibly burdened in the way no child should be as a doctor coldly tells him that his father will soon pass, a nurse instructing him to stay put and let them know when his father is gone. Xiang impassively places a napkin over his father’s face, the undertakers bickering amongst themselves while deciding to do the funeral for free seeing as this child is now all alone and seemingly has no other family. Yet no one comes to take care of Xiang, he has to go home on his own and begins living independently eventually resorting to stealing lunch boxes at school only to be caught and scolded by a grumpy janitor who both tenderly offers him food but then roughly slaps him when he notices the boy is crying.

As Xiang is about to become, the old man, Zhang (Chin Shih-Chieh), is also a displaced person having travelled from the Mainland 50 years previously. He takes him to scavenge abandoned buildings meditating on what it is that gets left behind, why it has value to some and apparently not to others. Xiang himself was abandoned by his mother who took his older brother with her but chose to leave him with his father, wondering perhaps if he is valuable or not. Technically if not literally orphaned, Xiang is later reunited with his mother, Chun-lang (Hao Lei), but is then displaced himself, forced to move to the city and into the house she shares with her second husband and infant child. Like Zhang his mother came from the Mainland in search of a better life she did not find and is living with a sense of disappointed futility trapped in her marriage to a dejected and violent man (Leon Dai) while forced to support the family through sex work at a nearby hostess club frequented largely by Mainland gangsters.

Unanchored and insecure in his new environment, Xiang begins having strange dreams of his apparently absent brother Yi but his attempts to discover the truth about the past only further destabilise the foundations of his new home. His mother cannot fully embrace him because of her guilt over leaving him behind while unable to fully process the reality of what may have happened to Yi too frightened of the truth to risk poking around. His stepfather meanwhile is a haunted man, unable to work and seemingly the primary carer to their small child though neither them are ever really seen paying much attention to the baby. When Chun-lang tells Xiang that he is a stranger in their house, that she is no longer the mother she once was because she has married another man and has another child with him, she does so perhaps partly to encourage him to leave advising him to steer clear of his stepfather in a bid to keep him safe yet blaming herself for all the tragedy which has befallen her accepting it would not have happened if she had not “messed up” her life.

Perhaps this is why Xiang finds himself bonding with a decidedly strange middle-aged man he meets by accident in a public toilet. “Big Gun” paints himself as something of a big brother figure, suggesting that they can drift together travelling around on his moped. His conduct towards the boy is extremely inappropriate in more ways than one involving him in his life of petty crime, yet Xiang finds in him a sense of acceptance that he doesn’t get from the other adults along with a new sense of independence. Yet Xiang’s illusions are eventually shattered twice over, the first revelation paving the way for a greater loss of innocence in discovering the truth about his brother while the second perhaps leads him to feel that he really is alone, continually displaced, and entirely unanchored in a world with offers little prospect of warmth, affection, or a place to belong.

Like Zhang and his mother, Xiang is fails to settle in contemporary Taiwan lost amid a stream of constant dislocations and bound only for endless wandering. Yet staring into a mirror preparing for his fourth portrait he perhaps begins to forge an image of himself informed by those he’s drawn before and giving him the sense of confidence to survive the emptiness of the world around him. Beautifully shot with a lingering ethereality, Chung’s enigmatic storytelling coupled with the whimsical score lend a note cheerfulness to what in many ways is a fairly bleak situation but perhaps reflects the surreality of the boy’s life in his constant quest for belonging.

International trailer (English subtitles)