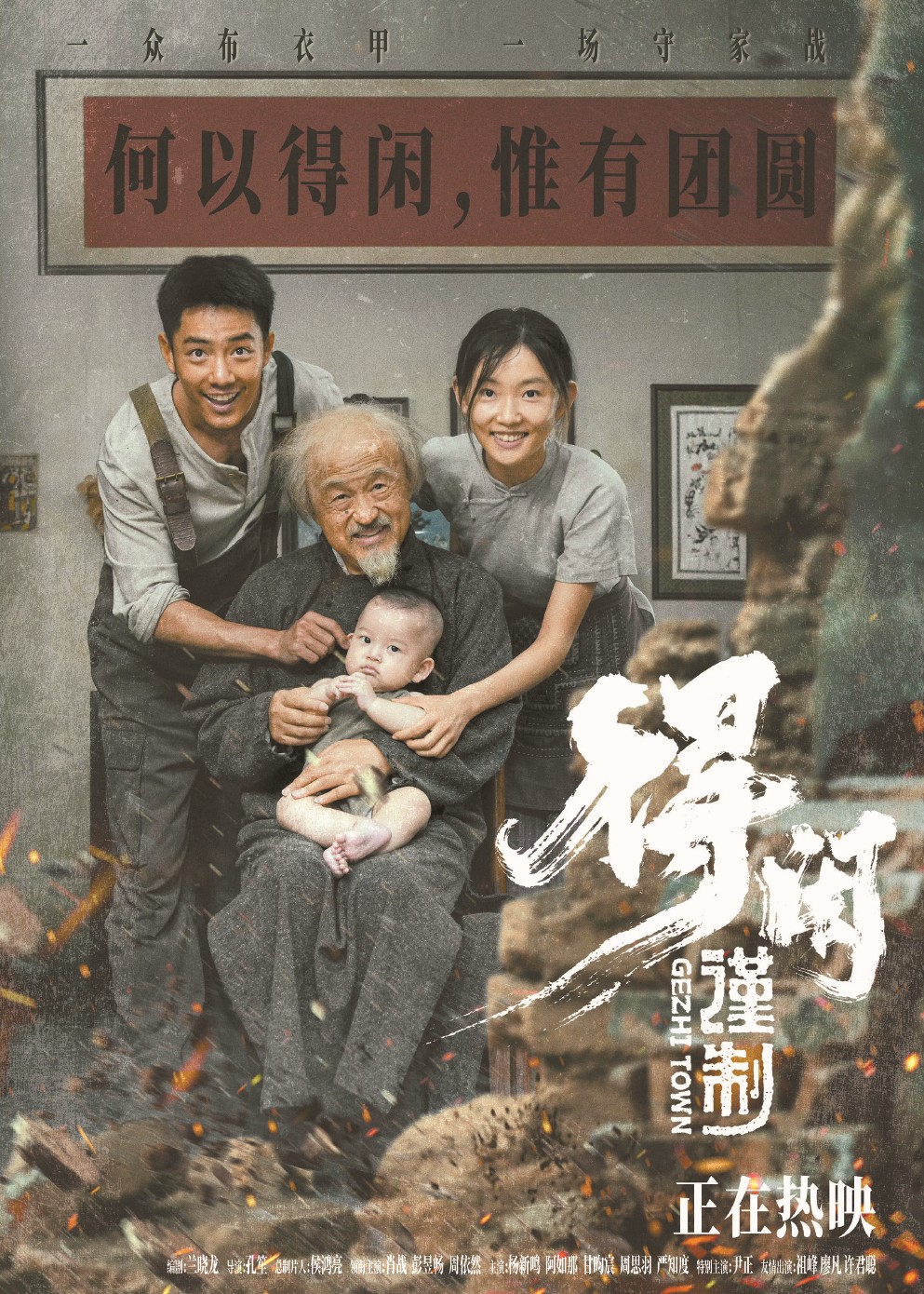

Fleeing the Japanese, a collection of former munitions factory workers and displaced soldiers take refuge in an abandoned village in Kong Sheng’s wartime action drama Gezhi Town (得闲谨制, dé xián jǐn zhì). Another in a series of films released to mark the 80th anniversary of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War alongside Dongji Rescue and Dead to Rights, the film is much more overtly propagandistic and an old-fashioned patriotism epic in which the hero’s quest to defend his home against the Japanese is quite obviously intended as a declaration that the modern China too will defend itself from incursion.

Indeed, Dexian (Xiao Zhan) says as much when risking his life to fire the artillery gun at a Japanese tank insisting that his resistance is not just for his own wife and child but for the future generations of the Chinese people. Getting in a few digs at Chiang Kai-Shek and the KMT, the film finds the heroes on the run implicitly denied their homeland in being forced into constant retreat. “I don’t want to die, I just want to go home,” the soldiers are fond of exclaiming, though already traumatised by their experiences, they’re effectively hiding from the war while attempting to create a new homeland in Gezhi Town after deciding to settle there rather than carry on along the road.

Captain Xiao (Peng Yuchang) might actually be the worst artillery officer in history and has a habit of making exactly the wrong decisions that put all his men in danger while fiercely defending an artillery gun he doesn’t really know how to use and has little intention of doing so anyway. A former munitions worker, Denxian was press-ganged into accompanying them to do maintenance on the guns, but Xiao has only been paying him in IOUs. Like everyone else, he just wants a home and is wary of being made “homeless” again if the Japanese turn up, so has been sharpening many of his tools and his wife’s domestic implements into makeshift weapons, much to her chagrin. Xia Cheng (Zhou Yiran) objects in part because she thinks it’s dangerous for their young son Dengxian who seems to have hearing loss as a direct result of his exposure to warfare when they were on the road.

But the problem is that when the Japanese actually arrive, the villagers are largely clueless. One challenges a Japanese soldier with a bakeshop bayonet but drops it and grins when the soldier lowers his weapon slightly. The soldier then bayonets him. Others run directly into the Japanese soldiers’s blades, while Xiao’s men randomly shoot all their bullets in one go then realise that they have no idea what to do now they’re essentially unarmed even though there are only three Japanese men in the village at this point. Only Denxian, the plucky civilian, knows what to do though even he originally gives the sensible advice to hide and wait for the Japanese soldiers to go away because they won’t have time to do an intensive search of every house.

Then again, the Japanese are quite stupid too and arrogant rather than cruel as they were in Dead to Rights even if constant references are made to Nanjing. Despite the grittiness of its storyline, the film is essentially a comedy filled with goofy humour along with Denxian’s winning hero antics as he resolves to do whatever he can to save his wife and son even if it costs his own life. When the Japanese first arrive, a kind of defeatism sweeps across the village that is only eventually broken by Denxian’s realisation that they don’t have to give in to their fate but might as well go out fighting. The film paints him as a kind of folk hero, echoed in the closing song recounting his exploits while the final title card says that he went on to use his skills in the resistance against American imperialism and the assistance of Korea. Xia Cheng fares a little less well. Despite singing a song about the new women, her role is limited to motherhood while Denxian’s love of his family is a metaphor for love of the nation as he desperately tries to reclaim a home in the wake of constant incursions. Nevertheless, the use of silent-film style intertitles and flashback scenes shot in the style of pathé news sequences add a degree of poignancy to this boy’s own adventure story.

Trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)