“As long as I keep writing, my existence has meaning,” according to the titular writer at the centre of Lu Yang’s action fantasy, A Writer’s Odyssey (刺杀小说家, cìshā xiǎoshuōjiā). His art, though derided as trivial, is it seems the best form of resistance to the feudalistic capitalism that has overtaken the authoritarianism of the communist past. Broken father Guan Ning (Lei Jiayin) desperately searches for his daughter Tangerine who has been missing six years, assumed to have been swallowed by China’s child trafficking network, only to find himself plagued by bizarre dreams of a fantasy city.

The city is, it seems, that of Kongwen’s (Dong Zijian) fantasy novel series which he live streams over the internet. Whenever something bad happens to the evil despot at the story’s centre, Lord Redmane, it’s visited on the CEO of vast corporation Aladdin (read: Alibaba), Li Mu (Yu Hewei), which has just launched the Lamp App which will they claim “resculpt time” so that time and distance are no longer an issue. Li Mu is panicked because Kongwen has said he’s going to end the series in three days and it doesn’t look good for Lord Redmane, so he’s fearful for his life. Noticing that Guan Ning has some sort of super power in which he can hurl rocks with unusual accuracy, he leverages Tangerine’s disappearance to convince him to knock off Kongwen in exchange for his daughter’s location.

Of course, the fantasy world and the “real” are connected in more ways than one with Ranliang conjuring visions of the Cultural Revolution in which the despotic leader is literally protected by hordes of mindless “Red Guards” while pitting one district against another and seemingly destroying all art. Li Mu, meanwhile, is destroying human innovation with his apps and treats the lives of others with callous disregard. His right-hand woman Tu Ling (Yang Mi), originally resentful of Guan Ning in blaming him for losing his child having been abandoned by her own parents, becomes disillusioned with his tactics on realising that he lied to Guan Ning and the candidates he picked for Tangerine are five random girls none which is likely to be her. Figuring out that she’s probably next after Li Mu knocks off Kongwen, who is also the son of his former business rival that he seemingly betrayed to take control of the company, and gets rid of Guan Ning for good measure, her allegiances begin to change creating a kind of parallel with Tangerine and the mysterious boy hanging around with her.

Meanwhile, in the fantasy world, Kongwen teams up with a demonic suit of armour that feeds on his blood but is also a near unbeatable killing machine that may or may not be evil. Guan Ning comes to believe that the fantasy world may be the only place he can find Tangerine and switches side from agreeing to kill Kongwen to deciding to protect him so that he can finish the story and possibly write a better ending for his fantasy character who as yet remains undefined. He’s later revealed to be a member of the brainwashed Red Guard, which may be appropriate as his former job was a banker which is to say a soldier of capitalism. Only art can break his programming in the form of Tangerine’s flute playing which reawakens his humanity and memory.

The implication seems to be that China cannot escape either its communist past or capitalist future except through the liberation that comes with artistic endeavour. When Guan Ning is tasked with killing Kongwen, he follows him about town and hears his neighbours run him down as a “parasite”, a man of almost 30 with no real job and no income who is still being financially supported by his mother. This information might be offered to make it seem less bad to kill him, as if in this hyper-capitalistic society his life is worth nothing because that’s what he contributes. Kongwen feels this a little himself and has suicidal thoughts, but also insists that his life has meaning precisely because he writes and expresses all of this frustration with the contemporary society along with his buried resentment towards Li Mu for the death of his father and theft of his birthright. Shot like a video game, the film’s sprawling fantasy-esque world hints at still more adventures to come in this David and Goliath competition in which Kongwen and Guan Ning attempt to overthrow this cruel and corrupt order to find a way to free themselves from its authoritarian cruelties if only in their minds.

Trailer (English subtitles)

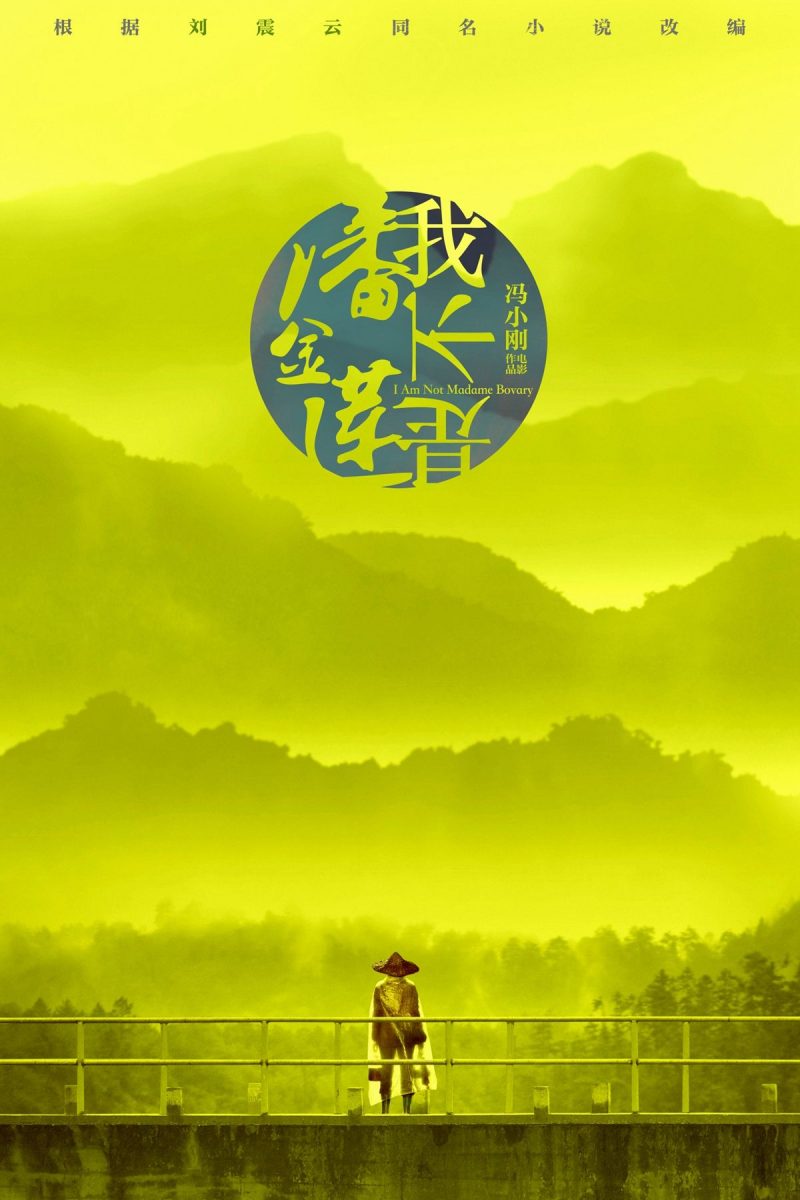

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and