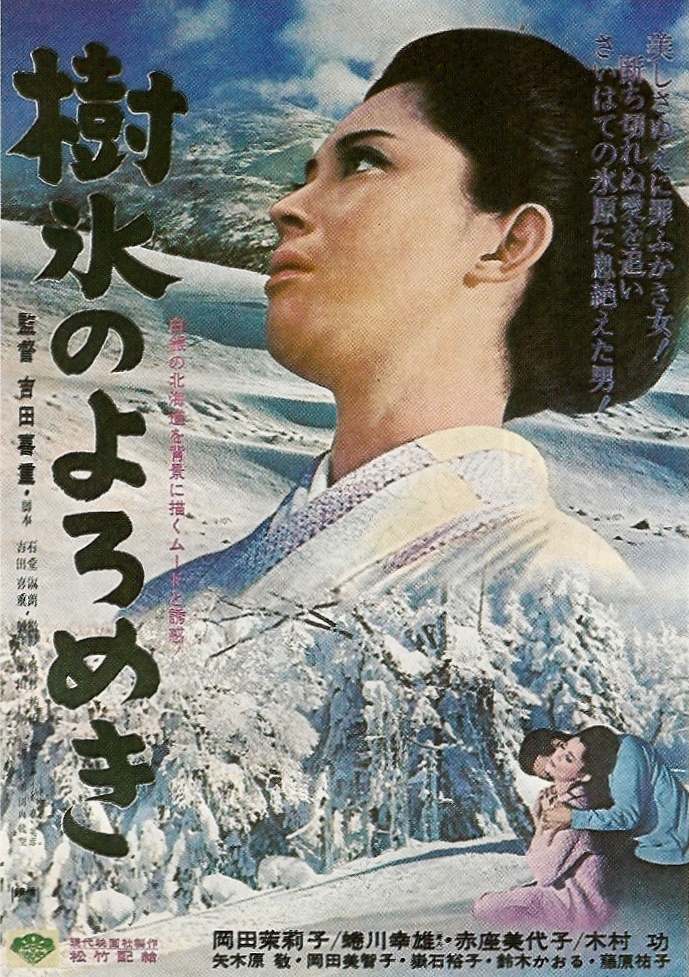

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida, along with his wife – the actress Mariko Okada, was responsible for some of the most arresting films of the late ’60s avant-garde art scene. So called “anti-melodramas”, many of Yoshida’s films from this era took what could have been a typical melodrama narrative and filmed it in an alienated, almost emotionless manner somehow reaching a deeper level of an often superficial and overwrought genre. Affair in the Snow (樹氷のよろめき, Juhyo no Yoromeki) is, in essence, the familiar story of an unreasonable love triangle but in Yoshida’s hands it becomes a melancholy yet penetrating examination of love, sex, and transience as the central trio attempt to resolve their ongoing romantic difficulties.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida, along with his wife – the actress Mariko Okada, was responsible for some of the most arresting films of the late ’60s avant-garde art scene. So called “anti-melodramas”, many of Yoshida’s films from this era took what could have been a typical melodrama narrative and filmed it in an alienated, almost emotionless manner somehow reaching a deeper level of an often superficial and overwrought genre. Affair in the Snow (樹氷のよろめき, Juhyo no Yoromeki) is, in essence, the familiar story of an unreasonable love triangle but in Yoshida’s hands it becomes a melancholy yet penetrating examination of love, sex, and transience as the central trio attempt to resolve their ongoing romantic difficulties.

Yuriko (Mariko Okada) works in an upscale beauty salon in Sapporo and is in a relationship with a moody professor, Akira (Yukio Ninagawa), which seems to have run its course. The couple decide to take a trip to figure things out but it all goes wrong when the car breaks down and they’re marooned together in an unfamiliar environment. Akira’s mood swings and jealousy seem to be the main motivators for Yuriko’s dissatisfaction along with his desire for rough and ready sex over genial romance. Fearing she may be pregnant, Yuriko is not sure what to do – especially given that Akira is not particularly supportive.

Running from Akira, Yuriko gets back in touch with an old friend and former lover, Kazuo (Isao Kimura), who she feels can be relied upon to help her whatever she decides to do in this admittedly difficult situation. Yuriko and Kazuo were together for a short while and still share a deep emotional connection but their relationship was eventually frustrated due to Kazuo’s physical impotence. Eventually Akira catches up with the pair and tries to win Yuriko back as the three work through their various problems in the snow covered mountains of Hokkaido.

For Yuriko the two men represent very different pulls – towards the spiritual and the physical. Her relationship with Akira has obviously long gone sour, the two aren’t suited or happy in each other’s company. All they have is the physical though, it seems, this is not enough for Yuriko. Yuriko and Kazuo, by contrast, work well together, complement each other and only exert positive energy but their inability to enjoy a full relationship (which it seems they would both like) is the reason their previous affair failed.

Yuriko needs, in a sense, both men though for the present time her desire is to be rid of Akira with his emotional volatility, cruelty, and possessiveness. Though the relationship may be been on its way out, Akira’s jealousy is inflamed by the deep connection Kazuo shares with Yuriko – bringing home the the fact that his relationship with her is firmly based in the physical. As Yuriko and Kazuo grow closer, Akira becomes increasingly unhinged as it’s he who’s now rendered “impotent” in the quest to win back his former love. Cavorting with the young hippies at the ski lodge, Akira tries to make Yuriko jealous and Kazuo irritated but only succeeds in making himself look ridiculous. Eventually, Yuriko is goaded into admitting that all Akira has ever known of her is superficial, whereas Kazuo has known her soul. Yet even so the love she shares with Kazuo seems doomed to fail, tinged with death as she finds herself blinded and obscured by snow filled fog, screaming into a void.

For Yoshida all love fails, as Kazuo says – no love can last. The central trio are lost and purposeless yet seeking a connection they never seem to find. Yoshida’s beautiful cinematography captures their emotional blankness through the freezing cold snow-covered landscape and infinite expanses of emptiness in which no one can reconcile everything that they want with everything that they are. Death lurks everywhere as skiers pulls bodies past romantic walks and would-be-lovers collapse in exhaustion as if trying to cross the artic plains in search of a lost friend.

Shooting through mirrors Yoshida shows us a collection of people unwilling to look directly either at themselves or at others, missing the final climactic event in their fierce determination not to engage. Lost in a fog, nothing is clear as the lovelorn and lonely seek direction only to remain locked inside themselves unable to find the true and complete connection they each seek.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

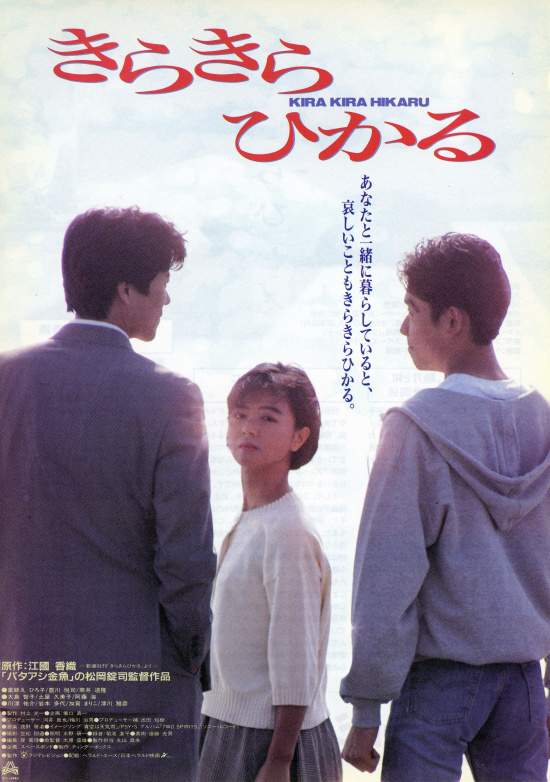

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as  When 21 year old Hitomi Kanehara’s Snakes and Earrings (蛇にピアス, Hebi ni Piasu) was published back in 2003 it took the coveted Akutagawa prize for literature and the country by storm. Its scandalous depictions of the dark and nihilistic sex life of its outsider youngsters outraged and fascinated enough people to get it onto the best seller lists and earn a cinematic adaptation from Japan’s top theatre director Yukio Ninagawa in only his second foray into the world of moving pictures. However, Snakes and Earrings is perhaps that rare instance of an adaptation which clings to closely to its source material as its detached, emotionless and straightforward approach end in something of a miss fire.

When 21 year old Hitomi Kanehara’s Snakes and Earrings (蛇にピアス, Hebi ni Piasu) was published back in 2003 it took the coveted Akutagawa prize for literature and the country by storm. Its scandalous depictions of the dark and nihilistic sex life of its outsider youngsters outraged and fascinated enough people to get it onto the best seller lists and earn a cinematic adaptation from Japan’s top theatre director Yukio Ninagawa in only his second foray into the world of moving pictures. However, Snakes and Earrings is perhaps that rare instance of an adaptation which clings to closely to its source material as its detached, emotionless and straightforward approach end in something of a miss fire.