By the late 1960s, Japan had more or less achieved its economic miracle yet there was still a degree of political tension manifesting itself in a second round of widespread protests towards the automatic renewal of the security treaty with the Americans in 1970. The third feature from Kiyoshi Nishimura, The Creature Called Man (豹は走った, Jaga wa Hashitta) anticipates the cinema of paranoia which was to take hold in the 1970s but as confused as its internal politics sometimes are, reflects the continuing sense of dissatisfaction in the wake of the student movement’s failure in its attempt to critique ongoing complicity with American foreign policy in Asia as well as Japan’s checkered geopolitical history.

As such, Nishimura opens with hand-coloured stock footage of civil unrest in an Asian nation while the accompanying voiceover features protestors chanting “down with Jakar”, later revealed to be the ousted dictator of “Southnesia”, seemingly a stand-in for the recently assassinated Sukarno of Indonesia. As opposed to the rather pompous English title, the Japanese is simply “Jakar got away”, a phrase repeated during the opening titles and which appears as “Jaguar got away” on a typewriter sitting above the Japanese title in red which uses the character for leopard in place of Jakar’s name. In fact, animal codenames will later become something of an ironic motif with the hero referred to as a German shepherd while his rival brands himself a wolf and is referred to by his handlers as the black panther.

This slightly tongue-in-cheek use of spy movie cliche is in keeping with the brand of humour often found in Toho’s ‘60s spy spoofs though this is largely a much more serious affair if one with an undercurrent of absurdity. The hero, Toda (Yuzo Kayama), is an Olympic sharpshooter working for the Tokyo police before he is abruptly asked to resign so that he can take part in a “special mission” which turns out to be as a backup bodyguard for Jakar who has been smuggled out of his home nation and intends to defect to America which has, it is implied, been backing his regime as a bulwark against communism in Asia while his rise to power was facilitated by Japanese soldiers who stayed in the country after the war. He’s supposed to be staying for a few days in a top hotel while the Americans figure out the paperwork for him to seek asylum at their embassy but the top brass are worried the revolutionaries might try to assassinate him on Japanese soil which would be very bad for diplomatic relations and potentially create political instability across the continent.

As Toda later says, he’s just doing his job (even though he’s technically no longer a policeman), so he doesn’t give much thought to the wider political context of his actions only concentrating on preserving a man’s life no matter now steeped in blood that life might be. Meanwhile, a duplicitous corporation, Dainihonboeki (lit. Great Japan Trading) is attempting to cut some shady deals apparently having facilitated Jakar’s escape but now frustrated that the Revolutionary Government won’t honour their contracts for military equipment and so is offering to help assassinate him to prevent his forming an alternative government in exile and creating additional problems for the new regime.

Kujo (Jiro Tamiya), the killer for hire, and the dutiful policeman Toda are exposed as two sides of the same coin, Toda later killing an innocent woman mistaking her for a member of the conspiracy against Jakar only to later learn she is in fact a war widow whose fiancé was an American GI killed in Vietnam. Her exaggerated death sequence filmed with expressionist flare in mimicking that of a soldier gunned down in battle. The two men face off against each other in what is essentially a battle of wits, Toda not taking aim at Kujo but anticipating his plan and foiling it before it takes effect. Leaning in to the Toho spoof, there is considerable absurdity in their machinations, waiters falling to the ground after the rope they were climbing to sneak in through a window is shot through, or sex workers brought in to shine a guiding light towards the target, but there’s a lot of blood and terror too not to mention some sleaze and a general sense of nastiness. Once the Jakar matter is concluded, the men still have a score to settle, facing off in a one-on-one duel in a disused aircraft hangar firing potshots at each other from behind various pieces of military equipment their life and death struggle shot in elegant slow motion until they each collapse into the swirling dust in a moment of nihilistic futility as another civil war quietly brews in Southnesia precipitated by their actions.

Strikingly composed capturing the neon-lit nightscape of an increasingly prosperous Tokyo filled with the shining lights of new corporate entities and scored with noirish jazz and occasional flights into expressionism, Nishimura’s paranoid political thriller takes aim at a new world of geopolitical instability while making villains of amoral capitalists and indulging in a mild anti-Americanism but most of all is a tug of war between a hitman inconveniently regaining his humanity and a policeman temporarily abandoning his in questionable national service.

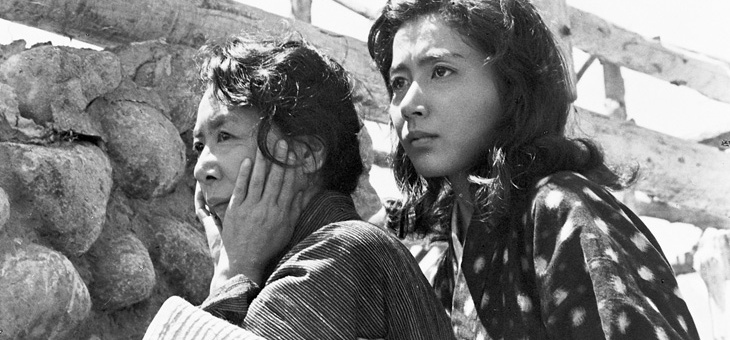

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession. Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from

Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from  Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of  The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as