A man in late middle-aged quite obviously living in the past begins to wake up to the possibilities of change in Wim Wenders’ Tokyo-set drama, Perfect Days. Even so, Hirayama’s (Koji Yakusho) days may be pretty much the same but that doesn’t necessarily mean that his life is dull or even predictable while it’s clear that he manages to find joy in small moments of serenity even if he may also seem to be harbouring a great sadness.

The irony is that Hirayama lives in a rundown postwar tenement that happens to be almost directly under the Tokyo Skytree which Wenders often cuts back to as if to signal the disparity between the rich and glitzy skyline of the contemporary city and the lives of those on its margins. Hirayama’s home has an almost eerie quality owing to the glowing purple light shining out of the window of his spare room where he nurtures tiny saplings back to health. The traditional-style two-floor flat has two tatami-mat rooms on the upper level, the other filled with books and cassette tapes amid an otherwise spartan interior. Before leaving for work each morning he brushes his teeth over the kitchen sink, the place has no bathroom, and meticulously takes up his belongings neatly placed in order on a shelf by the front door.

Perhaps it’s this kind of order that Hirayama craves, clinging to the security of the usual and dedicating himself to his work with unusual rigour. A municipal toilet cleaner, he painstakingly scrubs each and every bowl and urinal, checking the nozzles on the bidet function and shining a mirror underneath to make sure everything is as clean and tidy as it could possibly be only for drunken salarymen to push past him and quite literally piss all over his hard work. Like many such workers, he attains a kind of invisibility and should anyone need to use the facilities while he’s cleaning them he’s obliged to step outside and wait before starting all over again. When he finds a little boy crying alone in a park toilet he takes him by the hand and tries to help him find his mum, only when he finds her she completely ignores Hirayama and even goes so far as to wipe the boy’s hand with a wet wipe. The boy’s little wave of thank you as they leave is the only ray of comfort and recognition.

Yet for all that, it’s as if this the life Hirayama has chosen. He barely interacts with his chatty colleague Takashi (Tokio Emoto) who has a habit of rating everything out of ten and sees no value in his work, hardly bothering to do much cleaning at all while complaining that he has no money to romance the bar hostess he’s hoping to make his girlfriend. Takashi and Aya are fascinated by Hirayama’s collection of cassette tapes which he plays in his van, though Takashi more so for the commercial value that may be attached to them in a world in which everything old is new again and specialised stores in the trendy neighbourhood of Shimokitazawa trade exclusively in secondhand LPs and Sony Walkmans. Even so, Aya too appears to have her private sadnesses drawn to the voice of Patty Smith but pressing stop when the tape mentions suicide. The melancholy office lady in the park and an elderly homeless man who lives there too must have their own stories as unknown to Hirayama as his is to them.

A surprise visit from a teenage niece suggests that he may have come from a relatively wealthy family with a tyrannical patriarch and that this ascetic life of his is a kind of rebellion or else or a refuge, but there’s a look of pain on his face when the landlady at his favourite bar (played by enka legend Sayuri Ishikawa) laments that she wishes everything could stay the same. Perhaps he’s tired of this very analogue life and its otherwise pleasant monotony as he further confirms for himself realising that it’s not right for things not to change as he engages in a game of shadow tag with another middle-aged man who’s evaluating his life after a terminal cancer diagnosis. In truth, the film risks straying into orientalism in its advocation of Japanese serenity in simplicity (something not helped by the final title card explaining the term komorebi) while the musical choices appear a little on the nose and the celebration of mundanity in Hirayama’s labour might otherwise seem flippant. Even so, Yakusho’s typically astute performance keeps the film on an even keel as Hirayama finds himself on a turbulent journey towards a “new world” of fulfilment and possibility.

Perfect Days screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

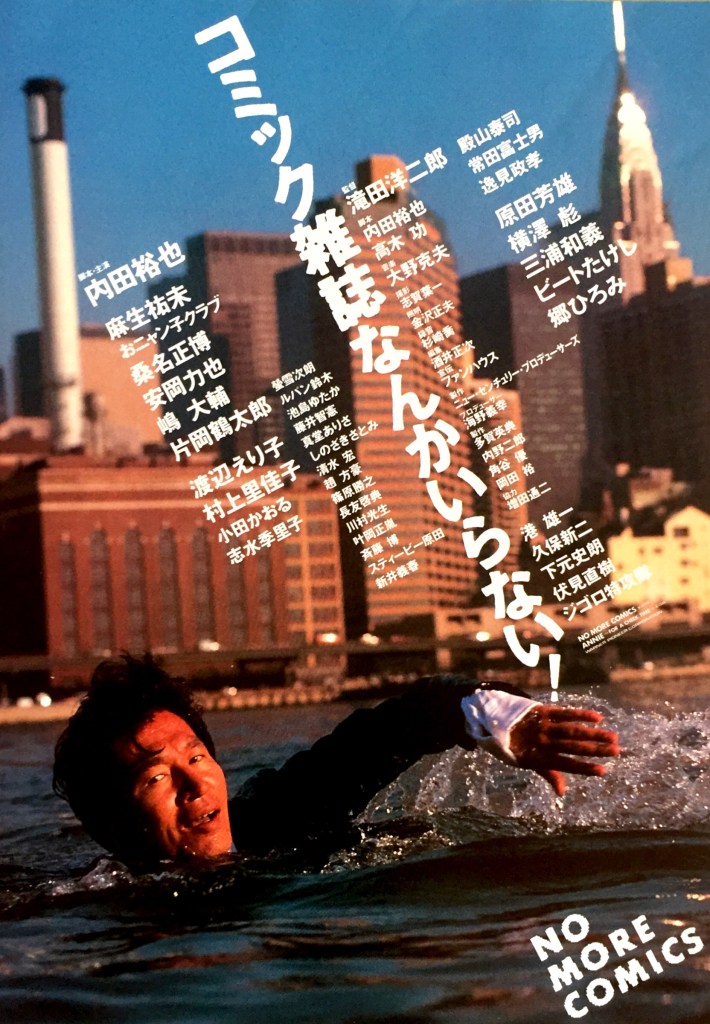

The word “paparazzo” might have been born with La Dolce Vita but the gossip hungry newshound has been with us since long before the invention of the camera. Yojiro Takita’s 1986 film No More Comics! (コミック雑誌なんかいらない, Komikku zasshi nanka iranai AKA Comic Magazine) proves that the media’s obsession with celebrity and “first on the scene” coverage is not a new phenomenon nor one which is likely to change any time soon.

The word “paparazzo” might have been born with La Dolce Vita but the gossip hungry newshound has been with us since long before the invention of the camera. Yojiro Takita’s 1986 film No More Comics! (コミック雑誌なんかいらない, Komikku zasshi nanka iranai AKA Comic Magazine) proves that the media’s obsession with celebrity and “first on the scene” coverage is not a new phenomenon nor one which is likely to change any time soon.