At the conclusion of 2014’s Samurai Hustle, it seemed that samurai corruption had been beaten back. Corrupt lord Nobutoki had got his comeuppance and the sympathetic “backwoods samurai” Naito was on his way home having found love along the way. Of course, nothing had really changed when it comes to the samurai order, but Naito was at least carving out a little corner of egalitarianism for himself in his rural domain.

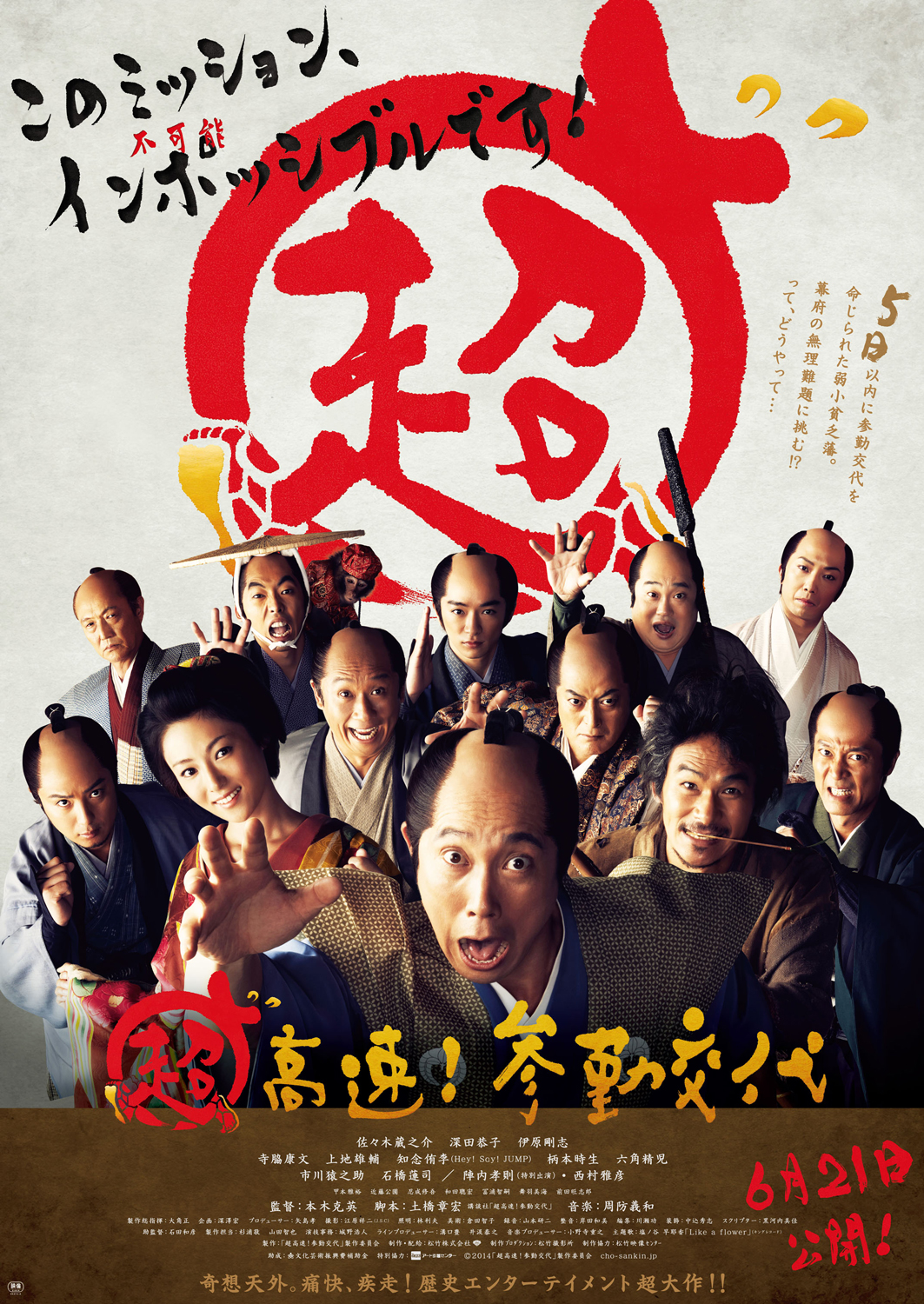

The aptly named Samurai Hustle Returns (超高速!参勤交代 リターンズ, Cho kosoku! Sankin kotai returns) picks up a month later with Naito (Kuranosuke Sasaki) taking a rather leisurely journey home in preparation for his marriage to Osaki (Kyoko Fukada) only to receive news that there has been a “rebellion” in Yunagaya. Predictably, this turns out to have been orchestrated by none other than Nobutoki who has been released early from his house arrest thanks to his close connections with the shogun but has been humiliated at court and is otherwise out for revenge with a slice of treasonous ambition tacked on for good measure. Just as in the first film, but in reverse, Naito and his retainers must try to rush home to get there before the imperial inspector arrives or else risk their clan being disbanded.

Meanwhile, the shogun is absent at the wheel after having decided to resurrect an old tradition abandoned because of its expense and inconvenience to make a pilgrimage to Nikko. In an interesting parallel, the farmers are uncharacteristically upset with Naito, blaming him for the destruction of their fields because he wasn’t there to protect them. Naito also feels an additional burden of guilt given that, having run flat out all the way to Edo, he took his time coming back leaving his lands vulnerable to attack while he now risks losing the castle. Nobutoki wastes no time at all looking for various schemes to undermine him while secretly plotting to overthrow the shogun and usurp his position for himself.

As in the first film, the battle is between samurai entitlement and the genial egalitarianism of Naito’s philosophy. “The real lords of Yunagaya are people like you who are one with the soil,” he tells the farmers, while Nobutoki sneers that “lineage rules supreme in this world, inherited wealth breeds more”. It doesn’t take a genius to read Nobutoki’s machinations as a reflection of his insecurity, that he invests so much in his rights of birth because he has no confidence in his individual talents. Naito counters that it’s the people around him that matter most, “people are priceless. Friends are priceless,” but Nobutoki rather sadly replies that people will always betray you in the end. Even the shogun eventually agrees that “anger brings enemies, forbearance brings lasting peace” but treats Nobutoki with a degree of compassion that may only embolden him in his schemes.

“Nepotism has endangered the shogunate,” the shogun ironically sighs apparently lacking in self-awareness even if beginning to see the problems inherent in the samurai society but presumably intending to do little about them. “No government should torment its people,” Naito had insisted on boldly deciding to retake his castle but even if this particular shogun is not all that bad, it’s difficult to deny that his rule is torment if perhaps more for petty lords like Naito than for ordinary people or higher-ranking samurai. Naito struggles to convince Osaki that she is worthy of his world and only finally succeeds in showing her that she has nothing prove and love knows nothing of class. The people of Yunagaya are impoverished but happy, satisfied with the simple charms of pickled daikon unlike the greedy Nobutoki whose internalised sense of inadequacy has turned dark and self-destructive.

Then again, Naito is still a lord. He obeys the system out of love for his clan and a genuine desire to protect those around him but otherwise has little desire to change it actively even if his quiet acts of transgression in his closeness with the villagers and professions of egalitarianism are in their own way a kind of revolution in a minor rejection of the shogun’s authority to the extent that the time allows. Nevertheless, with his return journey he once again proves the ingenuity of a backwoods samurai getting by on his wits as he and his men race home to save their small haven of freedom from samurai oppression from the embodiment of societal corruption.

Trailer (no subtitles)