“You’re not going to put this on the internet, right?” – a question asked by each of the interviewees in Park Jeong-hoon’s minimal yet riveting exploration modern mores A Confession Expecting a Rejection (거절을 기대하는 고백, geojeol-eul gidaehaneun gobaeg). Shot against green screen with a static camera and under a one take conceit, Confession interrogates everything from cinema as an art form and objective and subjective realities to social media, revenge porn, and romance among the young. Despite, or perhaps because of, the almost hypnotic lack of motion, Park’s meditations take on a surreal, almost mythic quality as interviewee and interviewer (seen or unseen) unwittingly dissect themselves before the passive lens of a seemingly unrecording camera.

“You’re not going to put this on the internet, right?” – a question asked by each of the interviewees in Park Jeong-hoon’s minimal yet riveting exploration modern mores A Confession Expecting a Rejection (거절을 기대하는 고백, geojeol-eul gidaehaneun gobaeg). Shot against green screen with a static camera and under a one take conceit, Confession interrogates everything from cinema as an art form and objective and subjective realities to social media, revenge porn, and romance among the young. Despite, or perhaps because of, the almost hypnotic lack of motion, Park’s meditations take on a surreal, almost mythic quality as interviewee and interviewer (seen or unseen) unwittingly dissect themselves before the passive lens of a seemingly unrecording camera.

The film opens with the camera “running” as its two operators chat amongst themselves whilst waiting for their interviewee. These interviews seem to be conducted weekly and are something to do with a university film club whose “director” is apparently somewhat pretentious and too much of a self-centred perfectionist to survive in less tolerant industries. Anyway, the first interviewee, Kyung-woo, joined the film group a few weeks ago and is, in the opinion of the men behind the camera, “a bit weird”.

Kyung-woo arrives and sits on a stool we can’t actually see because of the green screen. He seems nice enough – large round glasses, floppy hair, loose beige T-shirt. He starts chatting, introduces himself and reveals the unusual fact that he is already married. The interviewers are surprised and question him further, discovering Kyung-woo’s wife is currently living abroad, they had no wedding ceremony, and did not register their union with the government. At this point Kyung-woo’s demeanour changes, he seems spaced out but also intense as he begins to explain about meeting his wife at a “religious gathering” and how “the ancestors” that other people can’t see tell him who might be a good person to try “recruiting”.

During the short pause after Kyung-woo’s strange story, the guys behind the camera have a brief discussion about social media and a sex tape which has just gone viral – presumably an act of revenge porn. The next interviewee, Da-jeong, rushes in and ends their discussion. Unlike with Kyung-woo, one of the interviewers asks if Da-jeong would like a mirror to check her appearance before they start recording to which she seems surprised and laughingly declines – “it’s not as if I’ve come here to look pretty” she says. The same interviewer chit-chats about her part-time job as a tutor but is stunned into silence to realise she’s been tutoring a young man rather than a little girl. Unsurprisingly, interviewer 1, Han, will try and confess his love to her while interviewer 2, Jeong-gong, is out of the room.

Jeong-gong is, in fact, the boyfriend of Da-jeong whose previously cheerful demeanour dissipates just as Kyung-woo’s had only this time when faced with the increasingly intimidating presence of Jeong-gong. Da-jeong is trying to break up with Jeong-gong, but he refuses to listen. Explaining how “worried” it makes him when she doesn’t immediately answer her phone, Jeong-gong goes on to explain about a date but Da-jeong cuts him off – she won’t be coming, she doesn’t want to see him anymore. Jeong-gong ignores her, says she’s just in a mood and will change her mind after they get something to eat the next day. The implication is that Da-jeong has tried to do this before but has always backed down and intends today to be different. Unlike Kyung-woo’s rather strange tale of cults and early “marriage”, Da-jeong’s segment descends into brutal relationship drama as Jeong-gong’s increasingly manipulative behaviour keeps her from just up and leaving.

Park plays with the medium expertly. Making fantastic use of sound design to create a literally “unseen” world behind the camera, Confession allows its two interviewers to bicker irritatedly about their film course which teaches how to “see” in “layers”, picking up “emotional evidence” that the casual viewer might miss. Discussing the seen and the unseen along with the various “ranks” of student, the boys are beginning to sound just as surreal as Kyung-woo’s batty cultism. Talk of social media also smacks of cult with its “followers”, rituals, and precisely defined social codes but the conversations are essentially elliptical ending with a brief coda which returns us to origin as Da-jeong meets Jeong-gong and flicks the camera’s on switch herself, making a confession of love that ends in a promise we know will be broken.

Screened at the London Korean Film Festival 2017.

The

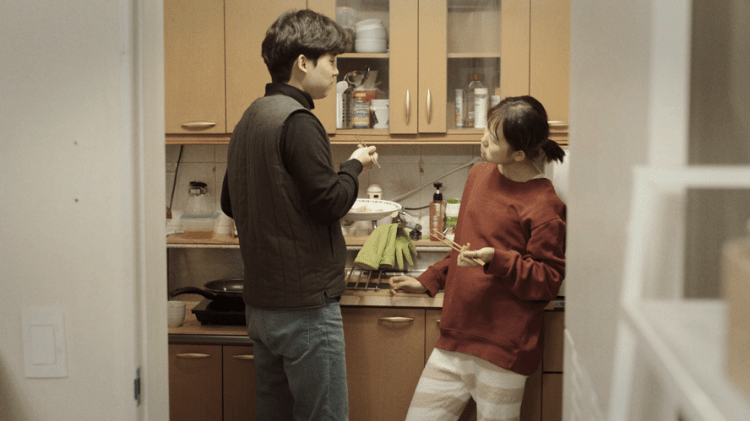

The  Closing the festival will be the second film from Kim Dae-hwan who picked up the best new director award at Locarno for this awkward tale of familial disconnection.

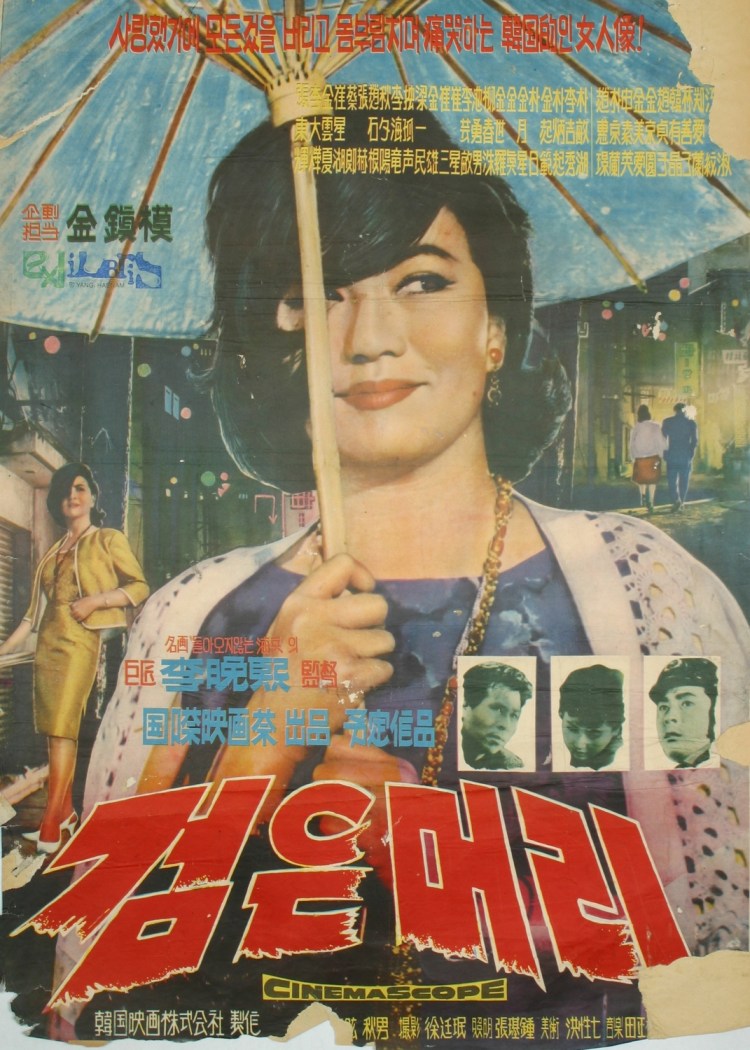

Closing the festival will be the second film from Kim Dae-hwan who picked up the best new director award at Locarno for this awkward tale of familial disconnection.  The special focus for this year’s festival is Korean Noir and Korean cinema has certainly had a long and proud history of gritty, existential crime thrillers. Running right through from the ’60s to recent Cannes hit The Merciless, the Korean Noir strand aims to illuminate the dark side of society through its compromised heroes and conflicted villains.

The special focus for this year’s festival is Korean Noir and Korean cinema has certainly had a long and proud history of gritty, existential crime thrillers. Running right through from the ’60s to recent Cannes hit The Merciless, the Korean Noir strand aims to illuminate the dark side of society through its compromised heroes and conflicted villains. The best in recent cinema across the previous year ranging from period drama to financial thriller, gangland action, social drama, and horror.

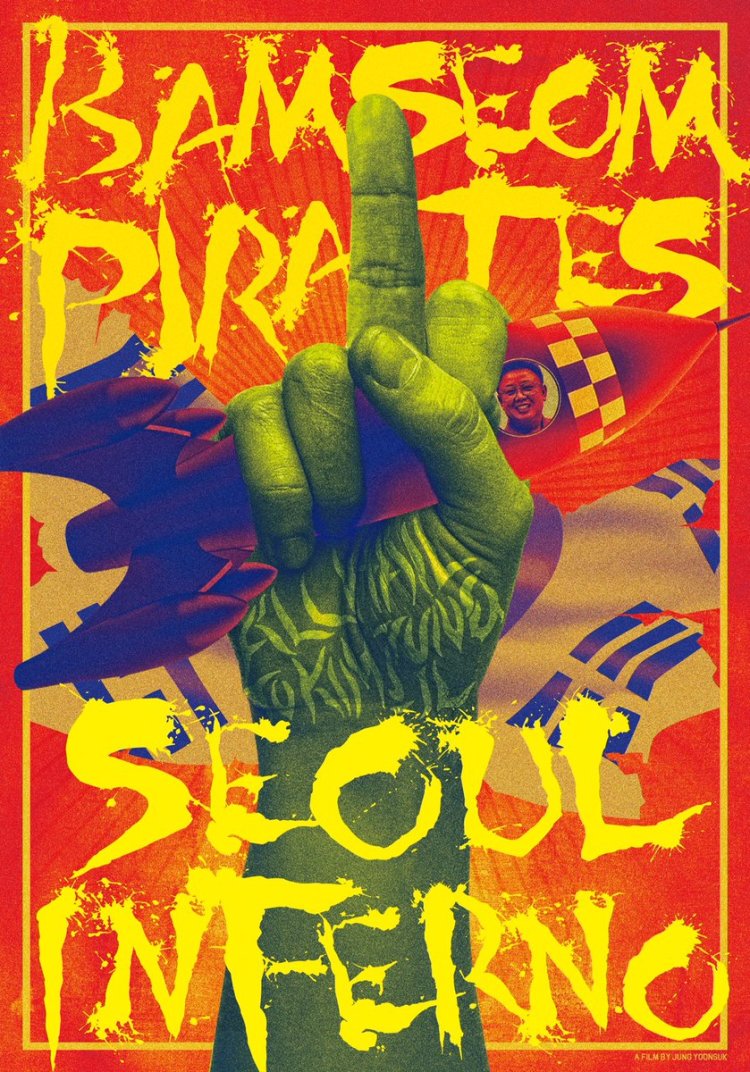

The best in recent cinema across the previous year ranging from period drama to financial thriller, gangland action, social drama, and horror. Programmed by Tony Rayns, this year’s indie strand has a special focus on documentary filmmaker Jung Yoon-suk who will be attending the festival in person to present his films.

Programmed by Tony Rayns, this year’s indie strand has a special focus on documentary filmmaker Jung Yoon-suk who will be attending the festival in person to present his films. Focussing on female viewpoints this year’s Women’s Voices strand includes one narrative feature and four short films.

Focussing on female viewpoints this year’s Women’s Voices strand includes one narrative feature and four short films. Three films from legendary director Bae Chang-ho each starring Ahn Sung-ki.

Three films from legendary director Bae Chang-ho each starring Ahn Sung-ki. Workers’ rights and examinations of the Yongsan tragedy in which five civilians and one police officer lost their lives during a protest against redevelopment dominate the feature documentary strand.

Workers’ rights and examinations of the Yongsan tragedy in which five civilians and one police officer lost their lives during a protest against redevelopment dominate the feature documentary strand. Two charming yet very different animated adventures aimed at a younger/family audience.

Two charming yet very different animated adventures aimed at a younger/family audience. A selection of shorts from the

A selection of shorts from the

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.