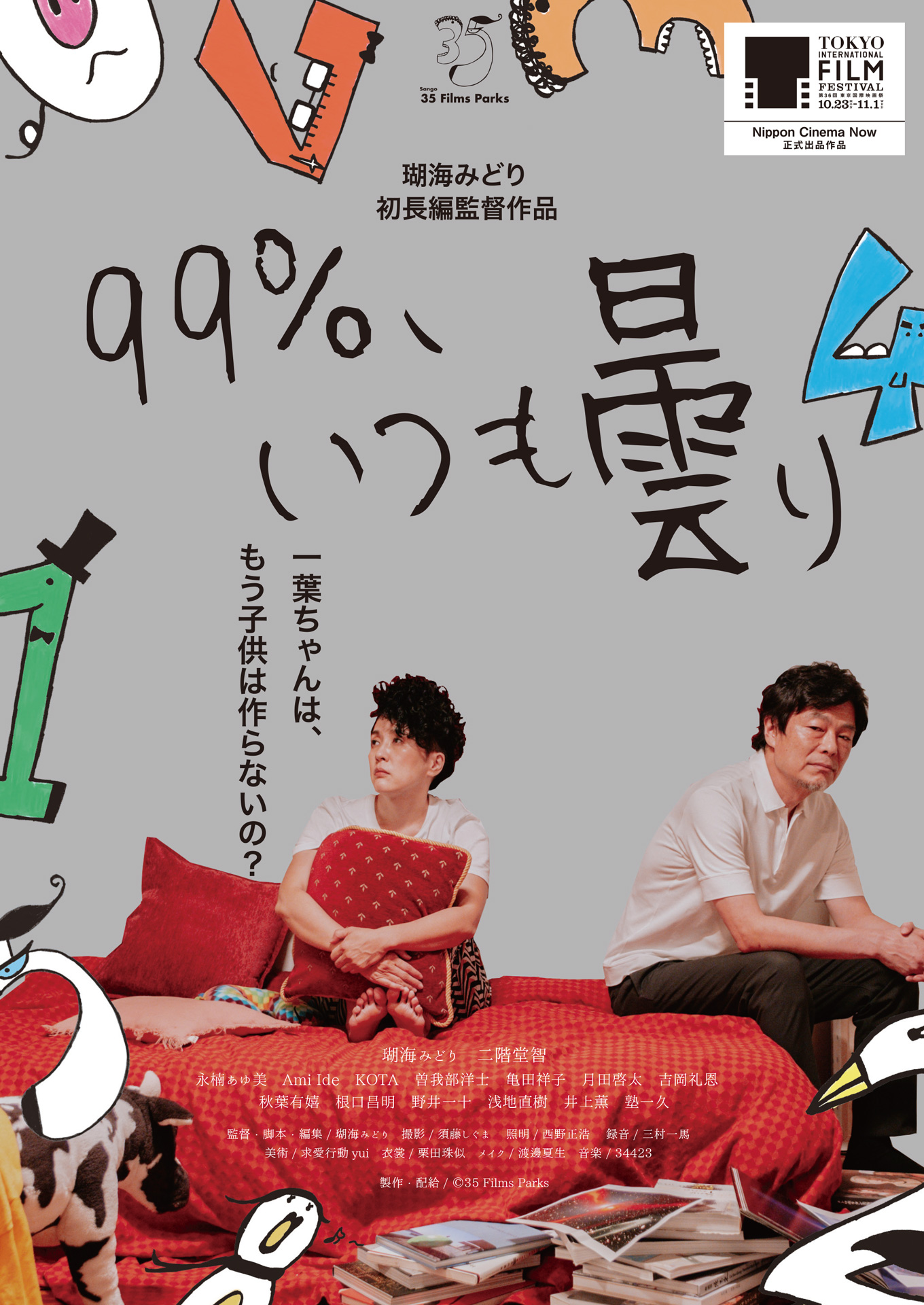

Beniko’s high school art project involves recreating a picture her mother left behind that immortalised a memory of a happy family moment during the rare sight of fireworks. But Beniko can’t seem to make progress with her artwork and she’s thinking of giving up art altogether along with her ambition of attending an art school because for her painting is intrinsically linked with her familial trauma and fears for the future. It is also, however, the force that keeps her family together though not perhaps in the way she intended.

The attempt to recreate her mother’s drawing is that to reclaim her family as it was though as she later realises attempting to recreate the past exactly is a futile effort. Resentful towards her mother for leaving and perhaps also towards her father for his emotional abandonment and the absurd jealousy that left her mother with no choice but to leave, she reinvents herself as a caretaker as a way of rooting herself in the domestic space by taking care of her autistic older brother Kyosuke, affectionately known around the neighbourhood as Kyon-kun. Looking after Kyon-kun is one reason she gives for not going to art school, but as her friend points out much to Beniko’s shame, perhaps that’s not really fair to him either if she’s exploiting his need as an excuse for her cowardice while denying him the right to his own life too. He is after all a little more capable than she might give him credit for, travelling to the correct station on his own and waiting for her patiently at the other end when she misses her regular train.

Beniko’s childhood friend Aoi later realises that he did something similar. When Kyon-kun wandered off while Beniko was distracted and climbed a tree at the shrine to watch imaginary fireworks, Aoi and his friend Kiichi, who is the son of the shrine owner, promised to set off some real fireworks for him without really thinking it through or having much intention to actually do it. But as Beniko points out, Kyon-kun never forgets a promise so now he’s asking every day when the fireworks are and is continually disappointed. Chastened by Beniko, Aoi’s half-hearted attempt to keep his promise backfires and he realises that he too thought that it didn’t really matter because it was Kyon-kun and he wouldn’t know the difference.

Aoi’s desire to make good on his word is partly a sense of guilt and shame in his realisation of the way he’d thought of Kyon-kun, partly due to his feelings for Beniko, and partly adolescent insecurity in the acceptance that his unnecessarily harsh father has a point when he says he never follows anything through. Kiichi too is experiencing similar anxieties as his father threatens to leave the shrine to his more studious younger brother and is exasperated by his goodhearted goofiness. The trio are all really looking for new paths towards adulthood by trying to make peace with their younger selves and gain the confidence to follow their dreams even if it takes them away from the picturesque settings of provincial Kurashiki.

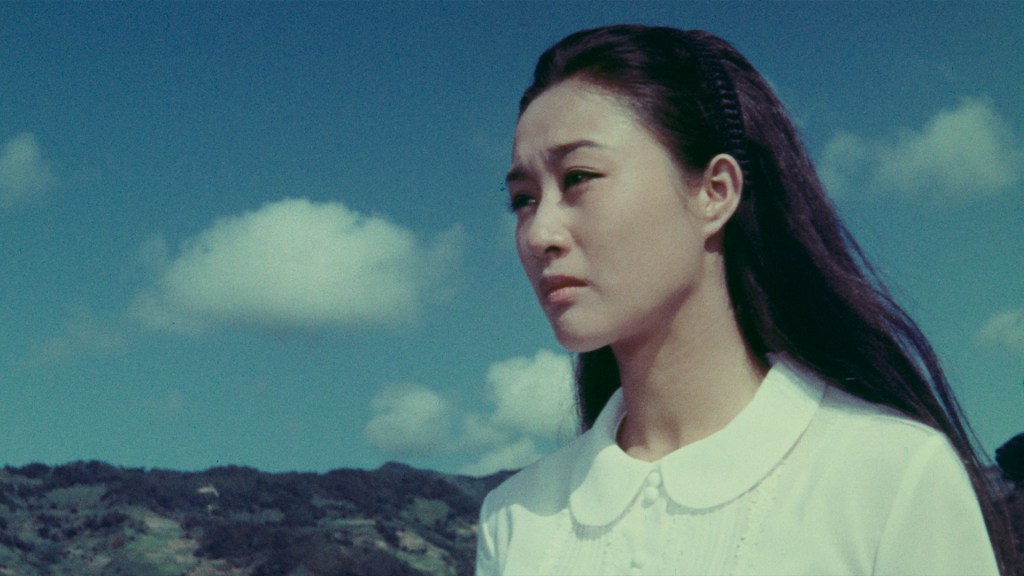

Beniko’s mother was fond of saying that there was a deity of waiting in the town, and there is a white-clad figure perhaps visible only to Kyon-kun who follows the youngsters around and looks on cheerfully as if embodying the sense of fun and warmth that lingers in the city. Kurashiki does indeed look like a nice place to live with its continual sunniness and traditional architecture though as someone points out that’s largely because the bombers flew past here and hit somewhere else instead. Fireworks are as apparent disruptor but eventual healer Kojo says a way of bringing people together, a source of joy happiness even amid difficult times just as they were during the pandemic. There’s something quite wholesome and comforting about the way the whole community comes together to make Kyon-kun’s dream come true, overcoming the obvious objections of the powers that be that it’s not a good idea to have a fireworks festival in a town that’s almost entirely constructed in wood to create a small marvel of human kindness and solidarity. It’s this that finally allows Beniko to remake her family, giving it her own light and colour while keeping a place for her mother having come to an acceptance of why she couldn’t stay and a conviction that she will one day return when she too has begun to heal her heart.

The Tales of Kurashiki screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Trailer (no subtitles)