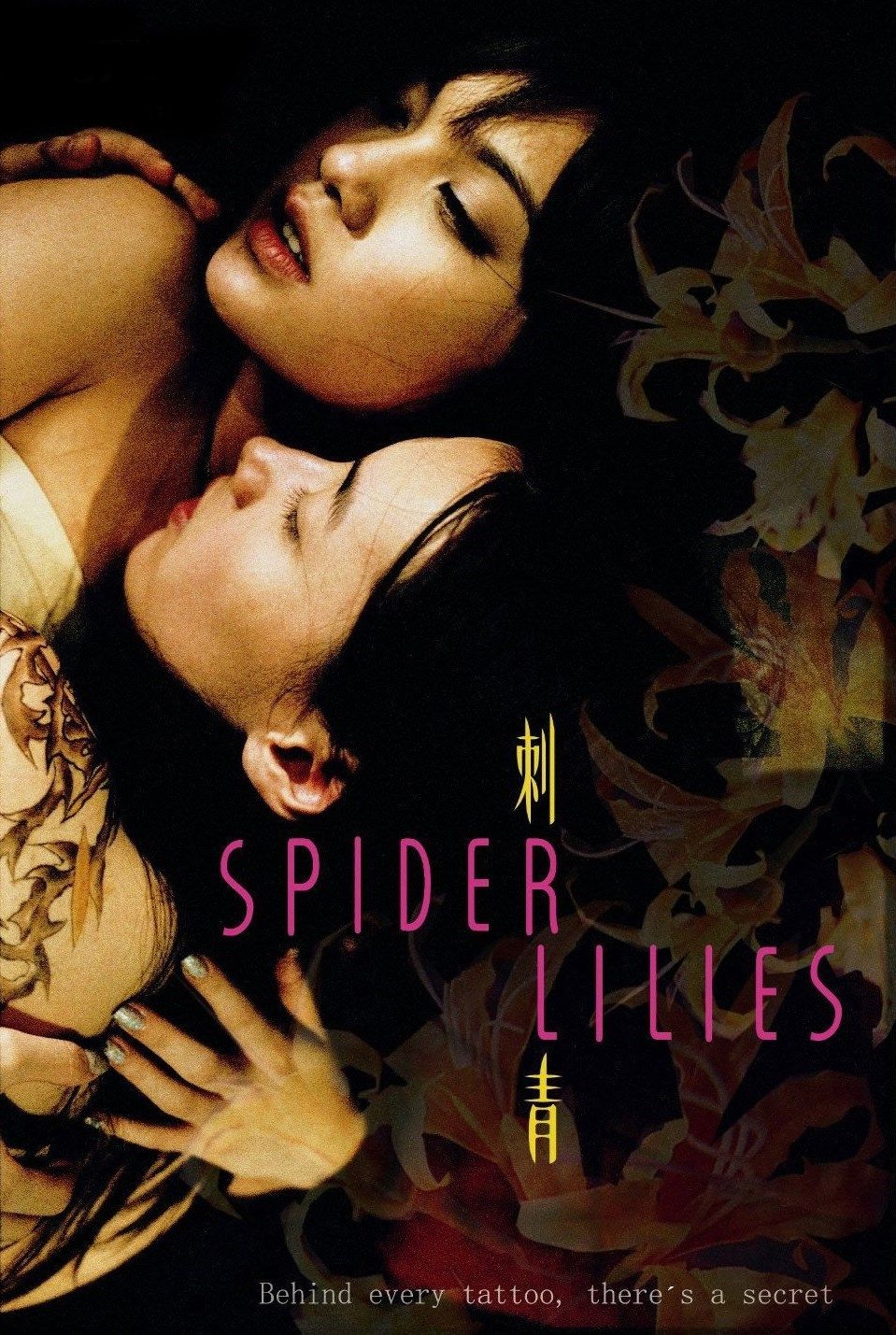

“I have no choice but to live in a virtual world” according to the lovelorn heroine of Zero Chou’s ethereal reflection on love and the legacy of trauma, Spider Lilies (刺青, Cìqīng). Two women connected by childhood tragedy struggle to overcome their respective anxieties in order to progress towards romantic fulfilment, eventually freeing themselves only by destroying the image of that which traps them.

In the present day, Jade (Rainie Yang) is an unsuccessful camgirl with a habit of shutting down her clients on a whim which doesn’t play well with her boss. In an effort to spice up her live show, she decides to get a raunchy tattoo only to realise that the tattooist, Takeko (Isabella Leong), is in fact her long lost first love, a neighbour she took a fancy to at the tender age of nine. For her part, Takeko appears not to remember Jade but cannot deny the presence of her unusual spider lily tattoo, a version of which hangs prominently on her wall. Hoping to maintain contact, Jade decides to get the spider lily tattoo herself but Takeko is reluctant, explaining that the spider lily is a flower that leads only to hell.

According to Takeko’s master, there is a secret behind every tattoo and the responsibility of the tattooist is to figure out what it is but never reveal it. Thus Takeko crafts bespoke tattoo designs for each of her clients designed to heal whatever wound the tattoo is intended to cover up, such as the ghost head and flaming blades she tattoos on a would-be gangster who secretly desires them in order to feel a strength he does not really have. Her tattoo, however, is intended as a bridge to the past, a literal way of assuming her late father’s legacy in order to maintain connection with her younger brother (Kris Shen) who has learning difficulties and memory loss unable to remember anything past the traumatic death of their father in an earthquake which occurred while she was busy with her own first love, a girl from school. Feeding into her internalised shame, the tattoo is also is a means of masking the guilt that has seen her forswear romance in a mistaken sense of atonement as if her sole transgression really did cause the earth to shake and destroy the foundations of her home.

Then again, every time Takeko seems to get close to another woman something awful seems to happen. Jade, meanwhile, affected and not by the same earthquake is burdened by the legacy of abandonment and the fear of being forgotten. Living with her grandmother who now has dementia the anxiety of being unremembered has become acute even aside from the absence of the mother who left her behind and the father last seen in jail. “Childhood memories are unreliable” she’s repeatedly told, firstly by Takeko trying to refuse their connection, and secondly by a mysterious online presence she misidentifies as her lost love but is actually a melancholy policeman with a stammer charged with bringing down her illicit camgirl ring. The policeman judgementally instructs her to stop degrading herself, having taken a liking to her because he says he can tell that she seems lonely.

A kind of illusionary world of its own, Jade’s camgirl existence is an attempt at frustrated connection, necessarily one sided given that her fans are not visible to her and communicate mainly in text. It’s easy for her to project the image of Takeko onto the figure of the mystery messenger because they are both in a sense illusionary, figments of her own creation arising from her “unreliable” memories. Jade wants the tattoo to preserve the memory of love as a bulwark against its corruption, at once a connection to Takeko and a link to the past, but the tattoo she eventually gets is of another flower echoing the melancholy folksong she is often heard singing in which the lovelorn protagonist begs not to be forgotten.

“I am a phantom in your dream and you too live in mine” Jade’s mystery messenger types, hinting at the ethereality of romance and fantasy of love. Caught somewhere between dream and memory the women struggle to free themselves from the legacy of past trauma and internalised shame, but eventually begin to find their way towards the centre in making peace with the past in a sprit of self-acceptance and mutual forward motion.

Spider Lilies streams in the UK 26th April to 2nd May courtesy of Queer East

Original trailer (English subtitles)