Does surviving in the modern society necessarily mean sacrificing your essential self? The eponymous Kim Min-young of the Report Card (성적표의 김민영, Seongjeongpyoui Kim Min-young) says she wants to transfer from her regional uni to one in Seoul because her classmates are “too Korean” and she finds them tedious, but is simultaneously mean to and dismissive of the film’s heroine, Junghee (Kim Ju-a), who has defiantly decided to follow her own path rather than the one society lays in front of her.

As the film opens, Junghee is one of three members of the “acrostic poetry club” along with her high school roommate Min-young (Yoon Seo-young), and a girl from down the hall Sanna (Son Da-hyun). Sadly, they’ve decided to wind the club up because they’re only 100 days out from the college entrance exams and need the extra time to study. We never find out exactly how well Junghee fared or whether her decision to lend her watch to an anxious boy (who does not pass) affected her grade, but in any case she does not attend university deciding instead to look for work while Min-young leaves to study nursing in Daegu.

The third girl, Sanna, as we later discover did the best of the three and went all the way to Harvard. The trio had vowed to carry on the poetry club via Skype, Sanna making time for her friends even though the time difference makes it inconvenient while Min-young seemingly can’t be bothered to turn up. Nor can she really take time out for Junghee’s calls, her friend a little put out to hear loud party music in the background while trying to share important news. Even so, she’s delighted when Min-young suddenly invites her to visit her staying at her brother’s vacant apartment in Seoul during the summer holidays especially as she’d just been let go from the random job she’d managed to get manning the desk at a moribund tennis club.

It’s in the Seoul apartment, a messy and chaotic place, that the differences between the two formerly close friends come to the surface. Despite having expressly invited her friend to come, Min-young isn’t really interested hanging out and is in the middle of some kind of crisis obsessing over a single bad grade on her end of term report card. Together they try to formulate a letter of complaint to the professor, Junghee doing her best to be supportive while privately wondering if Min-young isn’t being a little childish and that if she wanted a better grade she should have studied harder. Meanwhile, Min-young runs down all of Junghee’s life choices, constantly telling her she needs to be “realistic” and that she probably won’t get anywhere with her artwork in terms of financial viability.

Junghee is visibly hurt by Min-young’s superior attitude, but in the interests of having a pleasant day chooses to let it go even while Min-young continues to ignore her. Even so the difference between them is perhaps at the heart of Min-young’s ironic “too Korean” comment about her new uni friends, criticising them for the conventionality to which she too aspires, singing the praises of Seoul but most particularly for its three floor claw game emporiums. A quick look at Min-young’s diary when she abruptly takes off leaving Junghee alone in the apartment reveals that in actuality she envies Junghee for her boundless imagination and willingness to be her true self rather than blindly trying to fit in while finding herself out of place among her new friends. Her opening poem hinted at low self-esteem and an insecurity about the future that perhaps leaves her a little self-involved, projecting her anxieties onto Junghee who is eventually forced to defend herself by pointing out that she has her own reality which is important to her no matter what those like Min-young may have to say about it.

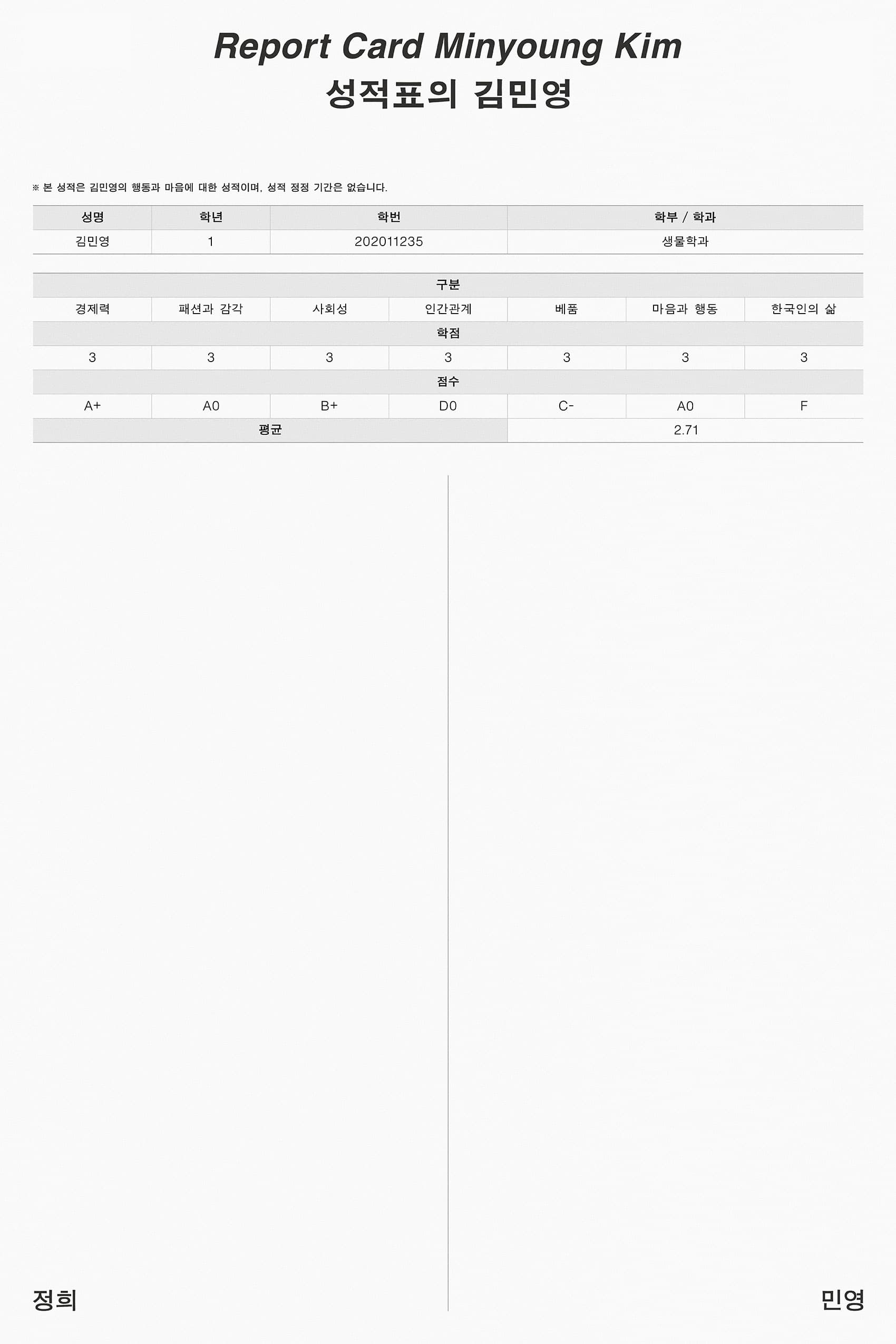

In the kindest of ways and with true generosity of spirit, Junghee writes the report card of the title praising her friend for her better qualities while pointing out her faults as supportively as she can. Giving her an “F” for “Koreanness” she advises her that she’s the one who is suffering because she worries too much about what other people think, searching for conventional “stability” rather than embracing her true self and ought to become “less Korean” in order to ease some of her anxiety. Offering a mild critique of a socially oppressive culture, Lee & Lim’s quirky drama with its random asides and flights of fancy makes a case for the right to dream positing the quiet yet free spirited Junghee as the more mature of the two women having embraced her true self and decided to follow her own path while being kind to those still trying to find their way.

Kim Min-young of the Report Card screened as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival

Original trailer (English subtitles)