Camera Japan returns for its 16th edition in Rotterdam 23rd to 26th September and in Amsterdam 30th September to 3rd October bringing with it another fantastic selection of the best in recent and not so recent Japanese cinema.

Feature Films

- 461 Days of Bento: A Promise Between Father and Son – a recently divorced single dad pledges to make a bento for his son every day for the next three years if he promises not to skip school in this heartwarming drama.

- Ainu Mosir – a grieving young man is confronted by the contradictions of his life as a member of an indigenous community in Takeshi Fukunaga’s poetic coming-of-age drama. Review.

- Along the Sea – a migrant worker from Vietnam is faced with her lack of possibility after discovering she is pregnant while living undocumented in Akio Fujimoto’s unflinching social drama. Review.

- Angry Rice Wives – a protest among fishwives against the sharp rise in the price of rice sparks nationwide unrest.

- Between Us – two young women begin to find the courage to expresses themselves through the power of music in this taiko drum coming-of-age drama.

- Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes – a diffident cafe owner faces an existential dilemma when trapped in a time loop with himself from two minutes previously in Junta Yamaguchi’s meticulously plotted farce. Review.

- Closet – a young man begins to understand loneliness and intimacy after taking a job as a sleep companion.

- The Fable: The Killer Who Doesn’t Kill – Junichi Okada returns as the hitman with a no kill mission in Kan Eguchi’s action comedy sequel which sees him come into conflict with a duplicitous philanthropist. Review.

- Georama Boy, Panorama Girl – lovelorn teens experience parallel moments of romantic disillusionment in Natsuki Seta’s charmingly retro teen comedy. Review.

- The Goldfish: Dreaming of the Sea – An anxious young woman begins to overcome her sense of trauma while bonding with a similarly lonely little girl in Sara Ogawa’s lyrical coming-of-age drama. Review.

- I Never Shot Anyone – an elderly writer’s decision to pose as a hitman as research for a novel gets dangerously out of hand when his wife suspects him of having an affair.

- It’s a Summer Film! – a jidaigeki-obsessed high schooler sets out to make her own summer samurai movie in Soshi Matsumoto’s charming sci-fi-inflected teen rom-com. Review.

- Kontora – a directionless high school girl finds a path towards the future through deciphering a message from the past in Anshul Chauhan’s ethereal coming-of-age drama. Review.

- Last of the Wolves – sequel to Kazuya Shiraishi’s Blood of Wolves set in 1991 in which a rogue cop attempts to keep the peace between yakuza gangs.

- Love, Life and Goldfish – musical manga adaptation in which a salaryman is demoted to a rural town after insulting his boss.

- LUGINSKY – experimental drama in which a man who hallucinates has trouble finding a job and spends his nights drinking and philosophising about life.

- My Name is Yours – Momoko Fukuda adapts her own novel in which a collection of Osaka teens experience the pain of youth.

- Ora, Ora be Goin’ Alone – an old lady living alone reflects on her life with the help of three strange sprites in Shuichi Okita’s moving dramedy.

- The Real Thing – a bored salaryman begins to chase the real thing after saving a distressed woman from an oncoming train in Koji Fukada’s beautifully elliptical drama. Review.

- Red Post on Escher Street – The extras reclaim the frame in Sion Sono’s anarchic advocation for the jishu life. Review.

- Remain in Twilight – a group of high school friends is forced to confront unresolved grief while rehearsing for a wedding in Daigo Matsui’s moving metaphysical drama. Review.

- Sasaki in My Mind – a struggling actor finds himself thinking back on memories of a larger than life high school friend in Takuya Uchiyama’s melancholy youth drama. Review.

- Shiver – dialogue free music movie from Toshiaki Toyoda filmed entirely on Sado island.

- The Town of Headcounts – a disaffected young man gets a fresh start in a utopian community but quickly becomes disillusioned in Shinji Araki’s slick dystopian thriller. Review.

- Under the Open Sky – a pure-hearted man of violence struggles to find his place in society after spending most of his life behind bars in Miwa Nishikawa’s impassioned character study. Review.

- Wife of a Spy – an upperclass housewife finds herself pulled into a deadly game of espionage in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s dark exploration of the consequences of love. Review.

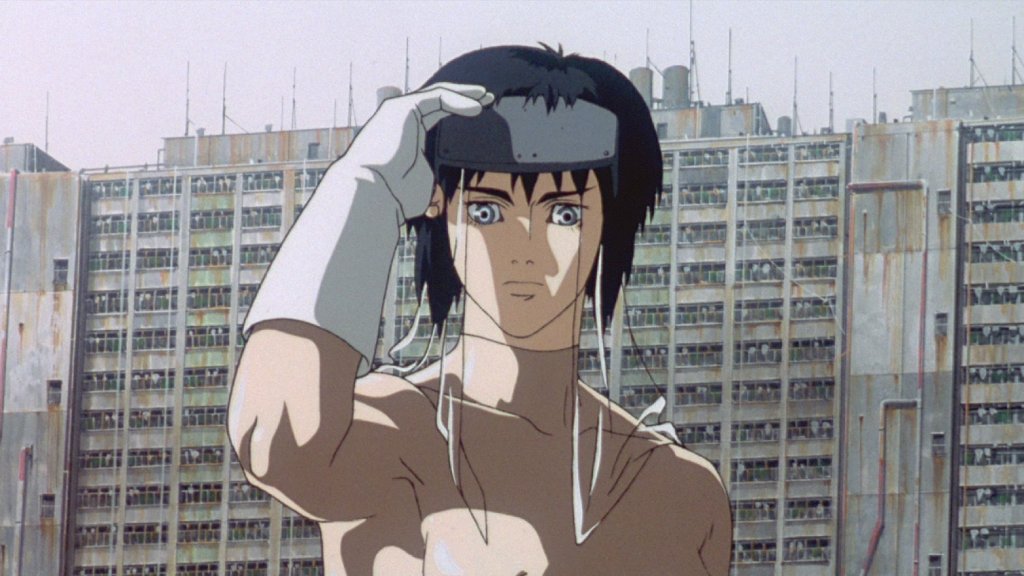

Animation

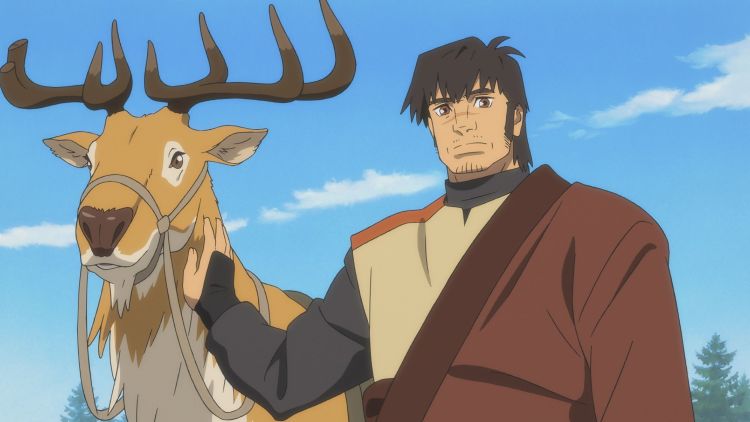

- The Deer King – animated feature in which a former soldier and a young girl attempt to escape a deadly plague.

- Junk Head– new theatrical edit of the sci-fi horror stop motion animation.

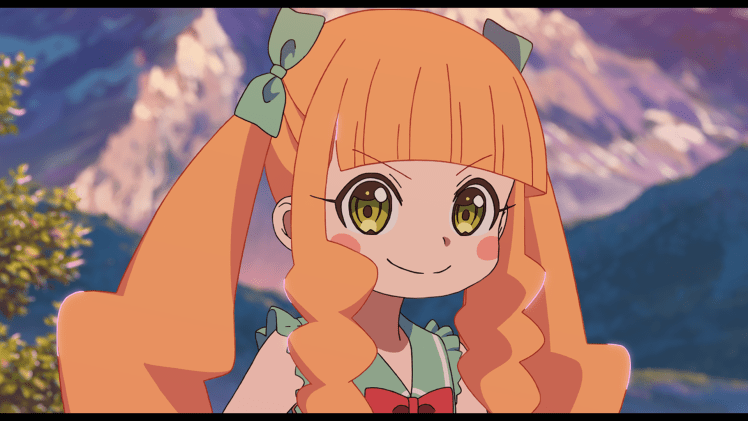

- Pompo the Cinephile – anime adaptation of the movie-themed manga.

Documentaries

- Bound – documentary focussing on female practitioners of traditional “shibari” bondage.

- Double Layered Town / Making a Song to Replace Our Positions – Four young travellers relate the stories of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in verbatim stage performances running concurrently with a fictional narrative set in 2031.

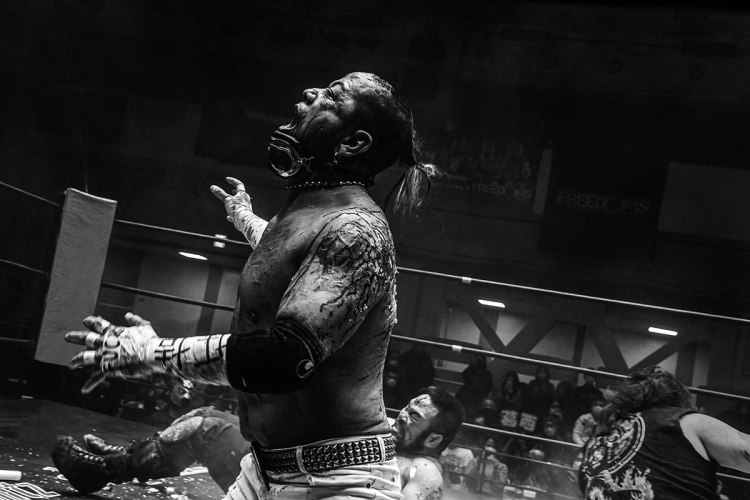

- Jun Kasai Crazy Monkey – documentary focussing on Japanese pro-wrestler “Crazy Monkey”.

- Okinawa Santos – documentary focussing on Okinawan migrants to Brazil and the their forced relocation during World War II.

- Ushiku – Filmed mainly with hidden camera, Thomas Ash’s harrowing documentary exposes a series of human rights abuses at the Ushiku immigration detention centre. Review.

Special Screenings

- A Straightforward Boy – Recently re-discovered silent short from Yasujiro Ozu in which gangsters kidnap a small boy but he’s so demanding they end up giving him back for free.

- Ghost Stories: Fox and Tanuki – early silent horror from 1929.

- The Ghost Cat and the Mysterious Shamisen – classic ghost cat horror from 1938 in which a jealous woman murders her rival’s cat which then comes back to haunt her as a vengeful ghost.

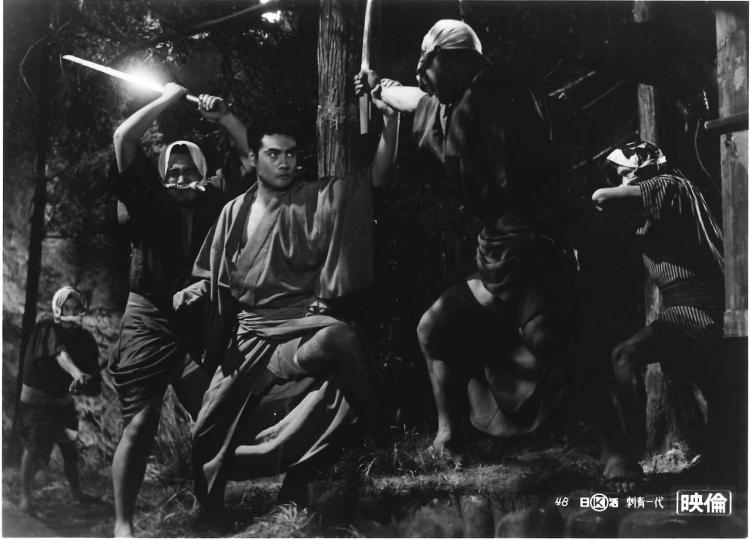

- Tattooed Life – nihilistic gangster drama from Seijun Suzuki.

Camera Japan 2021 takes place in Rotterdam 23rd – 26th September and Amsterdam 30th September – 3rd October. Full information on all the films as well as ticketing links can be found on the official website and you can also keep up to date with all the latest news via Camera Japan’s official Facebook page, Twitter account, and Instagram channel.