Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation.

Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation.

The case at the centre of the film centres around a young actor, Masaki Shibata, who has confessed to the murder of a pregnant woman and her husband after he argued with the woman at her place of work. Shibata acts strangely and makes a point of asking for the death penalty before spouting off about angels and demons and later displays evidence of a split personality. Everyone seems convinced he’s suffering from MPD and committed the murders during a dissociative episode but the assistant psychologist is convinced he’s faking. At the same time, one of the lead policemen on the case also thinks there’s more to this. On investigating further, he discovers the strange irony that the murdered man himself escaped prosecution by reason of insanity after committing a horrifying crime that lead to the death of a six year old girl.

The film may be about a murder but what’s really on trial here is the law itself. The murdered man, Hatada, committed a heinous crime but was a child himself at the time so received only a brief sentence served in a hospital. He was released, went to university, got a good job and got married – a normal life. The family of the little girl he killed, by contrast, will never be able to return to normality and will continue to live in torment for the rest of their lives knowing the man who so brutally took their child from them is still out there living just like one of us. The film does not go into why Hatada committed the original crime or the reasons he was later declared fit to return to society, but the film wants to question the idea of releasing back into the world someone who has done something as horrifying as the rape, murder and dismemberment of a child.

The case at hand is a complicated one which has so many layers coupled with twists and turns that it becomes unavoidably confusing. Playing with several literary allusions from the frequent quotations from the “mad prince” Hamlet to naming the assistant psychologist “Kafuka”, Keiho also wants to delve deep into human psychology with its questions of identity and self realisation. Both the accused and the psychologist have deeply buried memories of trauma the suppression of which has cast a shadow through the rest of their lives. Both of them are, in a sense (even if not quite in the way it originally appears), haunted by a shadow of themselves.

When it comes to the procedural aspects, the final “twist” is a step too far and perhaps undermines the groundwork which has gone before it. Something which is presented as an elaborate revenge plot against both the state and the original instigator of a crime also appears to originate with a clumsy motion of self preservation. The state’s failure to properly deal with the criminal in the first case has resulted the death of another innocent bystander, all of which might have been avoided if Article 39 had not come into play.

Kafka-esque is, in fact, a good way to describe the circularity of the narrative as the notion of an insanity plea becomes a recurrent plot device. Backstories are constructed and discarded, identities are shed and adopted at will and the past becomes a thorn in the side of the future that has to be removed so everyone can comfortably move on. Morita relies heavily on dissolves to create a floating, dreamlike atmosphere as memories (imaginary or otherwise) segue in and out like tides but he also shows us images reflected in other surfaces such as the Strangers on a Train inspired sequence which literally shows us events through someone else’s eyes as we’re watching them reflected doubly on the lenses of a pair of sunglasses.

Difficult, complicated and ultimately flawed Keiho proves an elusive and intriguing piece that is put together with some truly beautiful cinematography and interesting editing choices. Fascinating and frustrating in equal points Keiho is another characteristically probing effort from the wry pen of Morita which continues to echo in the mind long after the credits have rolled.

Keiho is available with English subtitles via HK R3 DVD as part of Panorama’s 100 Years of Japanese Cinema Collection.

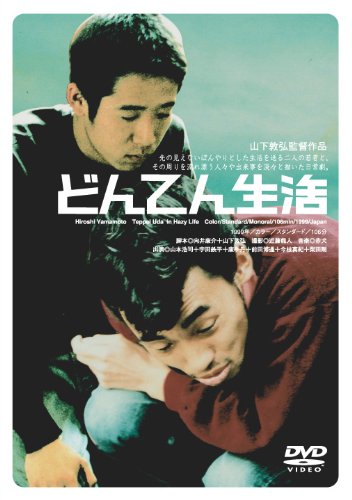

Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives.

Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives. The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.

The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.