How do you make a sequel to a film which ended with the apocalypse? Takashi Miike is no stranger to strange logic, but he gets around this obvious problem by neatly sidestepping it. Dead or Alive 2: Birds (DEAD OR ALIVE 2 逃亡者, Dead or Alive 2: Tobosha) is, in many ways, entirely unconnected with its predecessor, sharing only its title and lead actors yet there’s something in its sensibility which ties it in very strongly with the overarching universe of the trilogy. If Dead or Alive was the story of humanity gradually eroded by internecine vendetta, Dead or Alive 2 is one of humanity restored through a return to childhood innocence though its prognosis for its pair of altruistic hitmen is just as bleak as it was for the policeman who’d crossed the line and the petty Triad who came to meet him.

Signalling the continuous notions of unreality, we’re introduced to this strange world by a magician (Shinya Tsukamoto) who uses packets of cigarettes to explain the true purpose of a hit ordered on a local gangster which just happens to be not so different from the plot of the first film. Because the gangster world has its own kind of proportional representation, neither the yakuza nor the Triads can rule the roost alone – they need to enter a “coalition” with a smaller outfit no doubt desperate to carve out a little more power for themselves. The free agents, however, have decided on a way to even the power share – hire a hitman to knock off a high ranking Chinese gangster and engineer a turf war in which a proportion of either side will die, leaving the third gang a much more credible player.

Mizuki (Sho Aikawa), bleach blond and fond of Hawaiian shirts, is an odd choice for a secret mission but his sniper rifle is rendered redundant when a man in a dark suit does the job for him – loudly and publicly. So much the better, thinks Mizuki, but the memory of the strangely familiar figure haunts him. Finding himself needing to get out of town, Mizuki has a sudden urge to go home where he encounters the suited man again and confirms that he is indeed who he thinks he is – childhood friend, Shuichi (Riki Takeuchi).

Revisiting an old theme, Mizuki and Shuichi are orphans but rather than being taken directly into the yakuza world they each spent a part of their childhood in a village orphanage on an idyllic island. Miike frequently cuts back between the violent, nihilistic lives of the grown men and the innocent boyhood of long hot summers spent at the beach. The island almost represents childhood in its perpetual safety, bathed in a warm and golden light at once unchanging and eternal. Reconnecting with fellow orphan Kohei (Kenichi Endo) who has married another childhood friend, Chi (Noriko Aota), the three men regress to their pre-adolescent states playing on the climbing bars and kicking a football around just like old times.

Returning to this more innocent age, Mizuki hatches on an ingenious idea – reclaim their dark trade by knocking off those the world would be better off without and use their ill gotten gains to buy vaccines for the impoverished children of the world. In their innocent naivety, neither Mizuki nor Shuichi has considered the effect of their decision on local gangland politics (not to mention Big Pharma) and their desire to kill two “birds” with one stone will ultimately boomerang right back at them.

Innocence is the film’s biggest casualty as Miike juxtaposes a children’s play in which Mizuki and Shuichi have ended up playing a prominent role, with violent rape and murder going on in the city. Whether suggesting that the posturing of a gang war is another kind of playacting, though one with far more destructive consequences, or merely contrasting the island’s pure hearted fantasy with the cold, hard, gangland reality, Miike indulges in a nostalgic longing for the simplicity of childhood with its straightforward goodness filled with friendship and brotherhood rather than the constant betrayals and changing alliances of the criminal fraternity.

The question “Where are you going?” appears several times throughout the film and perhaps occurred to Mizuki and Shuichi at several points during their journeys from abandoned children to outcast men. Neither had much choice in their eventual destination and if they asked themselves that same question the answer was probably that they did not know or chose not to think about it. All of these hopes and ruined dreams linger somewhere around the island’s shore. Kohei is about to become a father but the birth of a child now takes on a melancholy air, the shadow of despair already hanging over him. There is no way out, no path back to a time before the compromises of adulthood but for two angelic hitmen, the road ends with meeting themselves again and, in a sense, regaining lost innocence in shedding their city-based skins.

Out now in the UK from Arrow Video!

Original trailer (English subtitles)

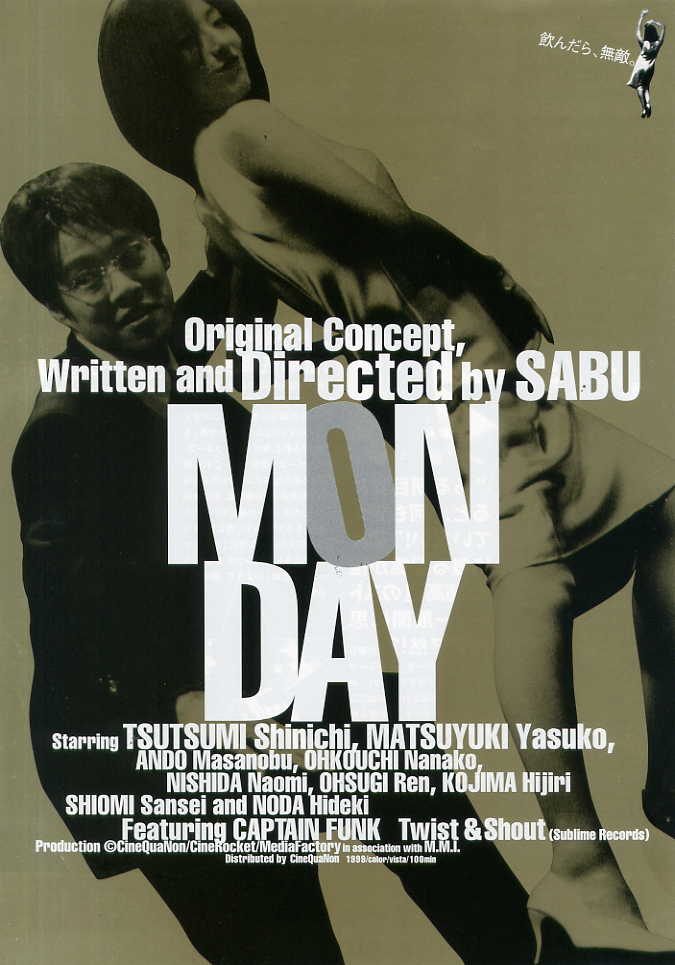

Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way.

Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way. Apichatpong Weerasethakul started as he meant to go on with his debut feature, straddling the borders between art film and surrealist exercise. A cinematic riff on the classic “exquisite corpse” game, Mysterious Object at Noon (ดอกฟ้าในมือมาร, Dokfa Nai Meuman) is equal parts neorealist odyssey and commentary on the human need for constructed narrative (something which the film itself consistently rejects). Shot in a grainy black and white, Apitchatpong’s first effort was filmed over three years travelling the length of the country from North to South inviting everyone from all walks of life to contribute something to the ongoing and increasingly strange brand new oral history.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul started as he meant to go on with his debut feature, straddling the borders between art film and surrealist exercise. A cinematic riff on the classic “exquisite corpse” game, Mysterious Object at Noon (ดอกฟ้าในมือมาร, Dokfa Nai Meuman) is equal parts neorealist odyssey and commentary on the human need for constructed narrative (something which the film itself consistently rejects). Shot in a grainy black and white, Apitchatpong’s first effort was filmed over three years travelling the length of the country from North to South inviting everyone from all walks of life to contribute something to the ongoing and increasingly strange brand new oral history. To date, Toshiaki Toyoda has released only one feature length documentary. Unchain (アンチェイン), the story of four boxers from Toyoda’s own home town of Osaka, was released between his debut feature,

To date, Toshiaki Toyoda has released only one feature length documentary. Unchain (アンチェイン), the story of four boxers from Toyoda’s own home town of Osaka, was released between his debut feature,  Not your mama’s jidaigeki – the punk messiah who brought us such landmarks of energetic, surreal filmmaking as Crazy Family and Burst City casts himself back to the Middle Ages for an experimental take on the samurai genre. In Gojoe (五条霊戦記, Gojo reisenki), Sogo Ishii remains a radical even within this often most conservative of genres through reinterpreting one of the best loved Japanese historical legends – the battle at Kyoto’s Gojoe Bridge . Far from the firm friends of the legends, this Benkei and this Shanao (Yoshitsune in waiting) are mortal enemies, bound to each other by cosmic fate but locked in combat.

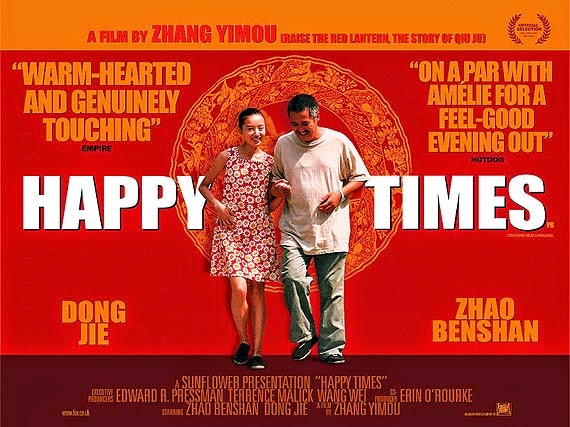

Not your mama’s jidaigeki – the punk messiah who brought us such landmarks of energetic, surreal filmmaking as Crazy Family and Burst City casts himself back to the Middle Ages for an experimental take on the samurai genre. In Gojoe (五条霊戦記, Gojo reisenki), Sogo Ishii remains a radical even within this often most conservative of genres through reinterpreting one of the best loved Japanese historical legends – the battle at Kyoto’s Gojoe Bridge . Far from the firm friends of the legends, this Benkei and this Shanao (Yoshitsune in waiting) are mortal enemies, bound to each other by cosmic fate but locked in combat. Possibly the most successful of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, Zhang Yimou is not particularly known for his sense of humour though Happy Times (幸福时光, Xìngfú Shíguāng) is nothing is not drenched in irony. Less directly aimed at social criticism, Happy Times takes a sideswipe at modern culture with its increasing consumerism, lack of empathy, and relentless progress yet it also finds good hearted people coming together to help each other through even if they do it in slightly less than ideal ways.

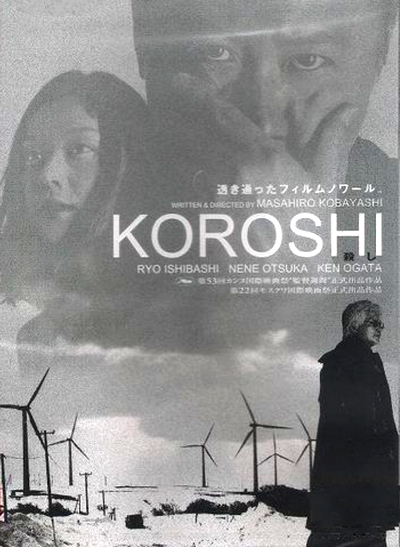

Possibly the most successful of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, Zhang Yimou is not particularly known for his sense of humour though Happy Times (幸福时光, Xìngfú Shíguāng) is nothing is not drenched in irony. Less directly aimed at social criticism, Happy Times takes a sideswipe at modern culture with its increasing consumerism, lack of empathy, and relentless progress yet it also finds good hearted people coming together to help each other through even if they do it in slightly less than ideal ways. Existential tales of hitmen and their observations from the shadows have hardly been absent from Japanese cinema yet Masahiro Kobayashi’s Film Noir (AKA Koroshi, 殺し) perhaps owes as much to Fargo as it does to Le Samouraï. Taking place in the frozen, snow covered expanses of Northern Japan, Kobayashi’s story is an absurdist one filled with dispossessed salarymen leading empty, meaningless lives in the wake of late middle age redundancy.

Existential tales of hitmen and their observations from the shadows have hardly been absent from Japanese cinema yet Masahiro Kobayashi’s Film Noir (AKA Koroshi, 殺し) perhaps owes as much to Fargo as it does to Le Samouraï. Taking place in the frozen, snow covered expanses of Northern Japan, Kobayashi’s story is an absurdist one filled with dispossessed salarymen leading empty, meaningless lives in the wake of late middle age redundancy.