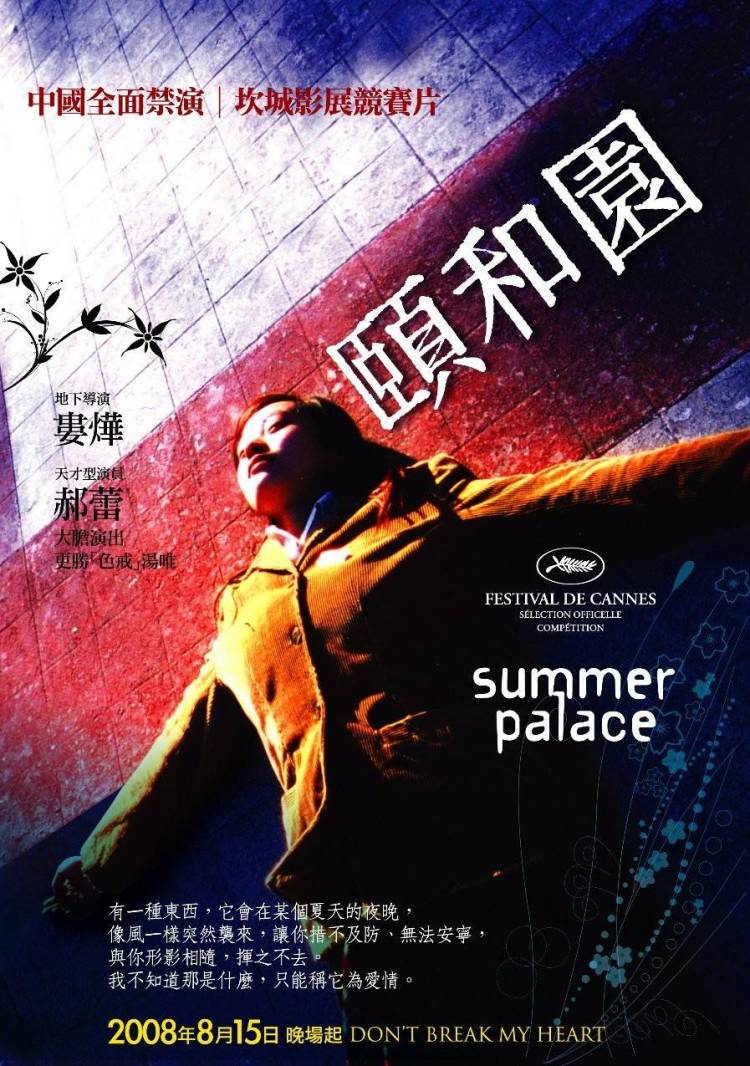

The personal is political for Lou Ye. Much as he had in Purple Butterfly, Lou paints love as a spiritual impossibility crushed under the weight of political oppression, though this time he leaves his protagonists breathing but wounded. Summer Palace (颐和园, Yíhé Yuán) is a member of a not exactly exclusive club of films deemed too controversial for the Chinese censors’ board. In truth, there are a number of reasons Lou’s wilfully provocative film might have upset the government, but chief among them is that he breaks a contemporary cinematic taboo in setting the Tiananmen Square massacre as the political singularity which causes the implosion of our protagonists’ youth, rendering them stunned, arrested, and empty. Personal and national revolutions fail, leaving nothing in their wake other than existential ennui and an inability to reconcile oneself to life’s disappointments.

The personal is political for Lou Ye. Much as he had in Purple Butterfly, Lou paints love as a spiritual impossibility crushed under the weight of political oppression, though this time he leaves his protagonists breathing but wounded. Summer Palace (颐和园, Yíhé Yuán) is a member of a not exactly exclusive club of films deemed too controversial for the Chinese censors’ board. In truth, there are a number of reasons Lou’s wilfully provocative film might have upset the government, but chief among them is that he breaks a contemporary cinematic taboo in setting the Tiananmen Square massacre as the political singularity which causes the implosion of our protagonists’ youth, rendering them stunned, arrested, and empty. Personal and national revolutions fail, leaving nothing in their wake other than existential ennui and an inability to reconcile oneself to life’s disappointments.

In the late ‘80s, Yu Hong (Hao Lei) gets a scholarship to study in Beijing and prepares to leave her home in a small rural town near the North Korean border for the promise of big city life. Yu Hong craves sensation, she wants to live life intensely and the inability to connect on a true, existential level leaves her feeling progressively empty and confused. A chance meeting with another girl in her dorm, Li Ti (Hu Lingling), brings her into contact with Zhou Wei (Guo Xiaodong) – a brooding intellectual and latterly the love of Yu Hong’s life, though one she becomes too afraid to embrace.

Yu Hong’s personal revolution, her quest for spiritual fulfilment largely through physical contact, occurs in tune with the chaos of her times. This is Beijing in 1988. The air is tense, anxious, as if hurtling towards an unavoidable climax. Yu Hong is not particularly political. She sees the protests, perhaps she agrees with them, but when she boards a pick up truck full of students waving banners and singing songs she does so more out of excitement and curiosity than she does out of commitment to political reform. Her tempestuous love affair with Zhou Wei mirrors the course of her city’s descent into chaos. Everything goes wrong, her heart is broken, something has been damaged beyond repair. Tiananmen Square, referenced only obliquely, serves as the event which traps an entire generation shell shocked by the brutal obliteration of their youthful hopes for a better world, leaving them imprisoned in a kind of limbo which prevents the natural progression from the innocence of youth to seasoned adulthood. They want the world to be better than it is but had the belief that it ever could be so brutally ripped away from them, that they are left with nothing more than a barren existence in which they cannot bear to touch the things they desire because they cannot believe in anything other than their own suffering.

Yu Hong’s early college days, marked as they are by rising anxiety, are also jubilant and filled with possibility. She dances innocently, nervously in a disco with Zhou Wei while a cheerfully wholesome piece of ‘50s American pop plays in the background – it’s this image Lou returns to at the end of the film. Something beautiful and innocent has been destroyed by an act of political violence, ruining the hearts of two soulmates who are now forever divided and bound by this one destructive incident. Yu Hong drops out of university and goes back to the country, bouncing around small town China occasionally thinking of Zhou Wei as an idealised figure of the love she has sacrificed, while Zhou Wei goes to Berlin and occasionally thinks about Yu Hong and missed opportunities. When they meet again years later it’s not an act of fate, or faith, or love but a prosaic interaction that leaves them both wondering “what now?”. There’s no answer for them, the future after all no longer exists.

As in Purple Butterfly, Lou makes history the enemy of love. Yu Hong didn’t ask for Tiananmen Square, she wasn’t even one of its major participants simply a mildly interested bystander, but she paid for it all the same in the way that history just happens to you and there’s nothing you can do about it. The youthful impulsivity, the naivety and craving for new sensations and expressions of personal freedom are eventually crushed by an authoritarian state, frightened by the pure hearted desire of the young to take an active role in the direction of their destinies. The quest for love and freedom has produced only loss and listlessness as a cowed generation lives on in wilful emptiness, their only rebellion a rejection of life.

Available to stream on Mubi UK until 10th September 2018.

Short scene from the film featuring “Don’t Break My Heart” by Heibao (Black Panther) which is also referenced in the poster’s tagline.

What do you do if you’ve just directed a box office smashing, taboo busting, giant mega hit? Well, you could direct Star Wars, but if you’re Lee Joon-ik you go back to basics with a low budget, heartwarming tale of friendship and failure. Radio Star (라디오 스타) reunites frequent costars Ahn Sung-ki and Park Joong-hoon whose shared history runs all the way back to ‘80s movies

What do you do if you’ve just directed a box office smashing, taboo busting, giant mega hit? Well, you could direct Star Wars, but if you’re Lee Joon-ik you go back to basics with a low budget, heartwarming tale of friendship and failure. Radio Star (라디오 스타) reunites frequent costars Ahn Sung-ki and Park Joong-hoon whose shared history runs all the way back to ‘80s movies  Coming in at the end of the “pure love” boom, Nobuhiro Doi’s second feature, Tears for You (涙そうそう, Nada So So) is presumably named to tie in with his smash hit debut

Coming in at the end of the “pure love” boom, Nobuhiro Doi’s second feature, Tears for You (涙そうそう, Nada So So) is presumably named to tie in with his smash hit debut  Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one.

Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one. Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own.

Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own. The somewhat salaciously titled Black Kiss (ブラックキス) comes appropriately steeped in giallo-esque nastiness but its ambitions lean towards the classic Hollywood crime thriller as much as they do to gothic European horror. Directed by the son of the legendary father of manga Osamu Tezuka (not immune to a little strange violence of his own) Macoto Tezuka, Black Kiss is a noir inspired tale of Tokyo after dark where a series of bizarre staged murders are continuing to puzzle the police.

The somewhat salaciously titled Black Kiss (ブラックキス) comes appropriately steeped in giallo-esque nastiness but its ambitions lean towards the classic Hollywood crime thriller as much as they do to gothic European horror. Directed by the son of the legendary father of manga Osamu Tezuka (not immune to a little strange violence of his own) Macoto Tezuka, Black Kiss is a noir inspired tale of Tokyo after dark where a series of bizarre staged murders are continuing to puzzle the police.

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.