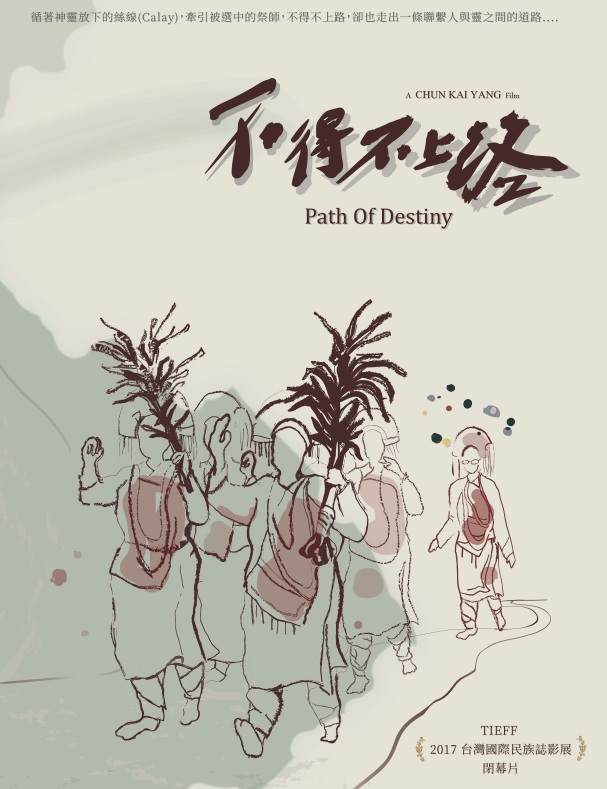

Taiwan’s indigenous culture is an all too often neglected facet of the island’s history, but as Yang Chun-Kai’s documentary Path of Destiny (不得不上路, Bùdébù Shànglù) makes plain, it is sometimes unknown even within its own community. Following researcher Panay Mulu who has been studying the Sikawasay shamans of the Lidaw Amis people in Hualien for over 20 years and has since become a shaman herself, Yang explores this disappearing way of life along with the (im)possibilities of preserving it for later generations in the fiercely modern Taiwanese society.

A member of the indigenous community though from a Christian family, Panay Malu recalls witnessing Sikawasay rituals in her childhood though only at the harvest festival. Her family’s religion made the existence of the Sikawasay a taboo, viewed as a kind of devilry to be avoided at all costs. Yet running into an entirely different kind of ritual, Panay found herself captivated not least by the beautiful ritualised music and thereafter began trying to gain access to the community who were perhaps understandably frosty in the beginning. Eventually she gave up her teaching position to devote herself to research full time and was finally inducted as a shaman becoming a fully fledged member.

Listening to the stories of the old ladies, they explain that those who become Sikawasay often do so after sufffering from illness, one of the main rituals involving a shaman using their mouth to suck out bad energy and cure illness. Yet they are also subject to arcane rules and prohibitions that they fear put younger people off joining such as refraining from eating garlic, onions, and chicken, and being required to avoid touch prior to certain rituals. Under traditional custom, widows are also expected to self isolate at home often for a period of years to avoid transmitting the “bad energy” of their grief to others.

Perhaps for these reasons, Panay is the youngest of the small group of Sikawasay who now number only half a dozen. A poignant moment sees her looking over an old photograph from a 1992 ritual featuring rows of shamans dressed in a vibrant red smiling broadly for the camera. The first row and much of the second are already gone, Panay laments, and as we can see there are only old women remaining with no new recruits following Panay in the 20 years since she’s been with them. Even one of the older women confesses that she would actually like to give up being a Sikawasay, it is after all quite a physically taxing activity with the emphasis on ritual singing and dance, but she fears being punished with illness and so continues. This lack of legacy seems to weigh heavily on Sera, the most prominent among the shamans, who breaks down in tears complaining that she often can’t sleep at night worrying that there is no one behind them to keep their culture alive save Panay who is then herself somewhat overburdened in being the sole recipient of this traditional history as she does her best to both preserve and better record it through academic study.

It’s a minor irony then much of her recordings exist on the obsolete medium of VHS, but one of the other old ladies is at least hopeful while taking part in the documentary that people might be able to see their rituals on their televisions in their entirety and the culture of the Sikawasay will not be completely forgotten. Panay expresses frustration that, ironically, their own culture is often explained back to them by external scholars from outside of the community, while another Amis woman praises her implying that their own traditional culture is something they have to relearn rather than simply inheriting. An old lady who says her husband was once a shaman though her son neglected his shamanic nature and left to study describes the Sikawasay as the “real Amis people”, vowing never to give up on shamanism though acknowledging there’s nothing much she could do about it if it disappears. In any case, through Yang’s documentary at least and Panay’s dedicated research, the rituals of the Sikawasay have been preserved for posterity even if their actuality risks extinction in the face of destructive modernity.

Path of Destiny streams in the UK 28th November to 5th December as part of Taiwan Film Festival UK

Original trailer (English subtitles)