Many, though not all, people have an interior monologue but what if you could converse directly with an image of yourself, a mental avatar who could talk and move around and might have opinions you would not expect to hear yourself say out loud? The scientists at the centre of Akiko Igarashi’s Mechanical Telepathy (メカニカル・テレパシー), a re-edited version of her 2017 feature Visualized Hearts, are working on a machine that can create a physical simulacrum of a mental image. No concrete reason is given for their research save that of one assistant who suggests its capacity to help those who can no longer communicate physically have a voice, but what quickly becomes apparent is that a self-created image may not be entirely reliable while the images of it held in other minds may differ in interesting ways.

Each of these philosophical questions begin to occur to scientist Mazaki (Ryuichi Yoshida) when he’s seconded to a research project as a kind of corporate spy on behalf of the business-minded boss who wants to put the product on the market as soon as possible despite the reservations of lead researcher Dr. Midori Mishima (Nanami Shirakawa) whose husband Soichi was injured in a previous experiment and is currently in a coma. Midori’s interest in the machine is then in its capacity to save her husband either by retrieving his bodily consciousness or preserving the image of him captured inside, improving and enhancing it until the point of communication.

But then as Mazaki comes to realise, perhaps the image of Soichi (Yoshio Shin) in the machine isn’t coming from his mind at all but from Midori’s in which case he doesn’t know anything she doesn’t know already and is in a sense inaccurate, composed only of her memories of him and necessarily limited in possessing the information she does not have even of this man whom she obviously knew intimately. Meanwhile, Mazaki also begins seeing an avatar of Midori, but is unsure if it originates from her mind, that of the comatose Soichi, or indeed his own as a means of confronting him with the desire he may feel for her. His image of himself meanwhile is scathing and self-loathing, challenging him over his various acts of moral cowardice in his essential inability to communicate his true feelings. Only assistant Asumi (Ibuki Aoi), harbouring a decidedly obvious crush on him, is brave enough to take him to task looking her own avatar in the eye and explaining that she has nothing to fear from herself. “If you don’t say it out loud no one will hear you” she explains though it’s a lesson that Mazaki in particular finds difficult to learn.

As for the avatars themselves, are they representations of particular people or indeed something new and different subject to influence and interference? The mind is supposedly free of time and space but that may not be an entirely good thing. What the machine posits is the separation between mind and body as if a soul could be sheared while it becomes difficult to say if the loss of corporality is liberation or imprisonment while Mazaki wonders if it’s right for a mind to exist without a body. If we can’t trust these images we have of others can we really trust those we have of ourselves which may be largely created through the way that others see us and we them? Complaining he can no longer distinguish whose mind he’s looking at, Mazaki finds himself caught in a moment of existential confusion amid several differing realities his own mind can no longer order.

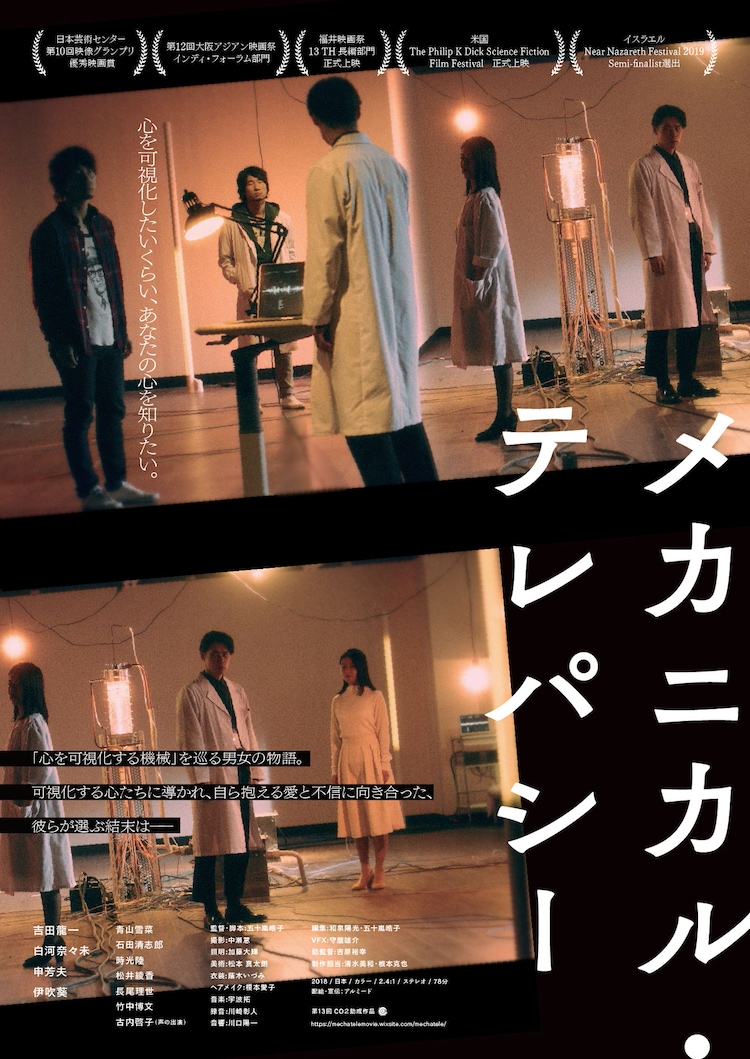

This sense of dissociation is perhaps replicated in Igarashi’s detached camerawork set amid the clinical glass and steal environments of the Kobe research institute where the experiments take place, the muted colour palette reflecting a sense of emptiness in the hearts and minds of the scientists who ironically remain incapable of direct communication. The near future production design similarly lends an air of sleek modernity to the otherwise vacant space while perhaps creating a sense of the supernatural in the lightning crackle inside the machine, its tangling wires a digital recreation of an analogue nerve system. A philosophical examination of the representation of the self, its projections literal and metaphorical, and the impossibility of knowing oneself or others Igarashi’s sci-fi drama eventually suggests that perhaps we are all in an empty room talking to ourselves incapable of understanding let alone expressing our true feelings.