Korean cinema is sometimes criticised for its bleakness. Happy endings are indeed something of a rarity, though not entirely absent and, ironically, often rejected for their sentimentality. Cinema for children might be a notable exception with the desire to cushion young viewers from the world’s harshness as a high priority even if it never shies away from the fact that life is sometimes hard and there will be times when you are sad or afraid or lonely. Astro Gardener (별의 정원, byeol-eui jeongwon), a colourful tale of strange creatures making sure the stars still shine, is a film about just those times which makes the very important and always relevant point that there is no light without darkness and that it’s OK to feel sad, or afraid, or alone because your darkness is also a part of you.

Korean cinema is sometimes criticised for its bleakness. Happy endings are indeed something of a rarity, though not entirely absent and, ironically, often rejected for their sentimentality. Cinema for children might be a notable exception with the desire to cushion young viewers from the world’s harshness as a high priority even if it never shies away from the fact that life is sometimes hard and there will be times when you are sad or afraid or lonely. Astro Gardener (별의 정원, byeol-eui jeongwon), a colourful tale of strange creatures making sure the stars still shine, is a film about just those times which makes the very important and always relevant point that there is no light without darkness and that it’s OK to feel sad, or afraid, or alone because your darkness is also a part of you.

12-year-old Suha (Kim Yeon-woo) is excited that her parents are going to leave her alone in the apartment overnight for the first time while they go on a fishing trip. Before he leaves, Suha’s dad gives her a precious necklace which she is not very impressed with because all she wants is a dog. Suha’s dad is broadly in favour of the puppy idea, especially as grandma’s dog is currently pregnant so it would be very easy to adopt one once it’s born. Mum is less convinced, both fearing that she will end up looking after it and worrying that it will be sad when the dog inevitably passes away. While they’re busy discussing all that on the way to the campsite, the car swerves to avoid an oncoming truck and they get into an accident during which Suha’s dad is killed.

A year later, Suha’s mum takes her to stay with grandma during the holidays while she has to get back to work. Suha isn’t very happy about it, but the blow is softened by the fact she’s finally getting a little dog named “Night” who is the last of grandma’s puppies seeing as her own dog passed away shortly after giving birth. Playing on the beach, Suha is drawn to a strange stone and takes it home only for a weird little man with a star on his head to break into her room and steal it. The man, who turns out to be called Om (Jeon Tae-yeol), is an “Astro Gardener” charged with looking after the darkness to ensure that the stars can stay in the sky. It turns out that the planet Pluto (Shin Yong-woo) has gone rogue and left its orbit to become a space pirate hellbent on destroying the darkness to create a universe of light born of the destruction of hundreds of stars.

A universe of light in which there is no more loneliness or pain might sound very attractive, but where there’s no sorrow there can be no joy. Since her father’s death, Suha has been deathly afraid of “the dark”, sleeping with the light on and only venturing out in the middle of the night when her dog chases out after Om, which is how she winds up discovering the Astro Garden. She isn’t terribly invested in the quest to save the darkness but finds herself swept into it when Pluto’s minions show up and kidnap Night’s shadow which means she has to go and get it back or risk loosing him because, as the repeated metaphor points out, you can’t live as light alone.

Om warns Suha that Pluto is a no-good rebel out to destroy the universe but because she loses a lot of her memory on his ship, Suha is instantly smitten seeing as it just so happens that Pluto looks exactly like the handsome K-pop idol we see on the poster in her bedroom. Realising that the necklace Suha received from her father is the All-Energy capable of controlling all the darkness in the universe (what teenage girl doesn’t think she can do the same?), Pluto sets out to take it but the snag is that the power can only be transmitted to someone you truly love which is the real gift her father was trying to give her.

Learning to remember her father’s love rather than his loss, Suha rediscovers her sense of confidence and is no longer so afraid of “the dark”. Resolving to be kinder to her mother, she can appreciate life’s light and shade but makes sure to keep in touch with her old friends at the Astro Garden to go tend to her darkness to make sure she can still see the stars. A cheerfully animated tale of a little girl figuring out how to live with grief while becoming embroiled in an interstellar battle to save the universe, Astro Gardner is a surprisingly deep meditation on depression and anxiety in which the heroine rediscovers her sense of self while finding the will to fight for others.

Astro Gardener screens on 2nd November as part of the 2019 London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

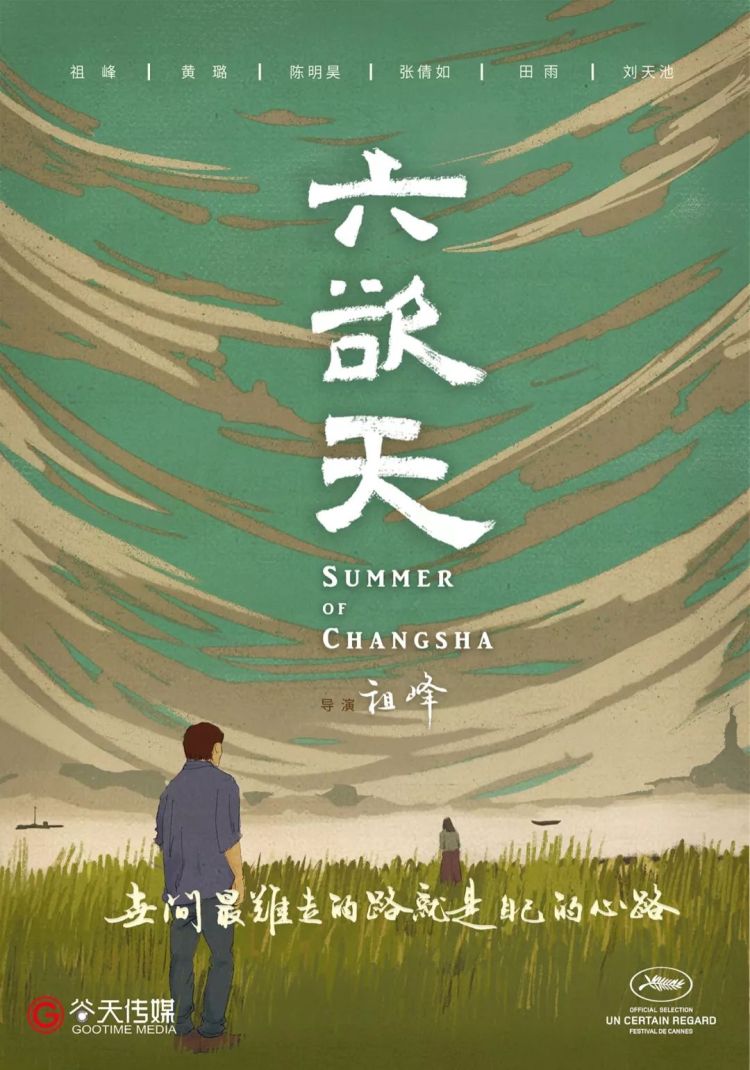

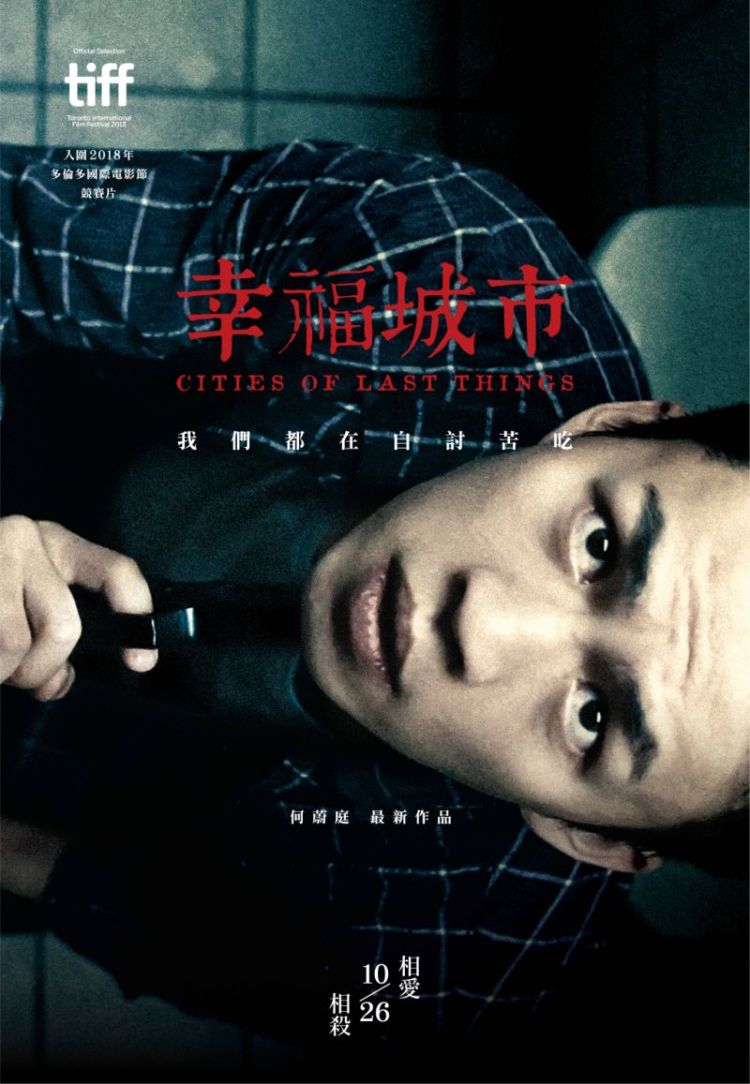

A sense of finality defines the appropriately titled Cities of Last Things (幸福城市, Xìngfú Chéngshì), even as it works itself backwards from the darkness towards the light. Still more ironic, the Chinese title hints at “Happiness City” (neatly subverting Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “City of Sadness”) but that, it seems, is somewhere its hero has never quite felt himself to be. Embittered by a series of abandonments, betrayals, and impossibilities, he grows resentful of the brave new world in which old age has marooned him.

A sense of finality defines the appropriately titled Cities of Last Things (幸福城市, Xìngfú Chéngshì), even as it works itself backwards from the darkness towards the light. Still more ironic, the Chinese title hints at “Happiness City” (neatly subverting Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “City of Sadness”) but that, it seems, is somewhere its hero has never quite felt himself to be. Embittered by a series of abandonments, betrayals, and impossibilities, he grows resentful of the brave new world in which old age has marooned him.

“Hell Joseon” manifests as “toxic gas” in Lee Sang-geun’s Exit (엑시트). Millennial “slackers” losing out in Korea’s increasingly cutthroat economy find themselves consumed by their own sense of failure while those around them only compound the problem by branding them useless, no-good layabouts, writing off the current generation as lazy rather than acknowledging that the society they have created is often cruel and unforgiving. Yet, oftentimes those “useless” skills learned while having fun are more transferable than one might think and the ability to find innovative solutions to complex problems something not often found in the world of hierarchical corporate drudgery.

“Hell Joseon” manifests as “toxic gas” in Lee Sang-geun’s Exit (엑시트). Millennial “slackers” losing out in Korea’s increasingly cutthroat economy find themselves consumed by their own sense of failure while those around them only compound the problem by branding them useless, no-good layabouts, writing off the current generation as lazy rather than acknowledging that the society they have created is often cruel and unforgiving. Yet, oftentimes those “useless” skills learned while having fun are more transferable than one might think and the ability to find innovative solutions to complex problems something not often found in the world of hierarchical corporate drudgery.