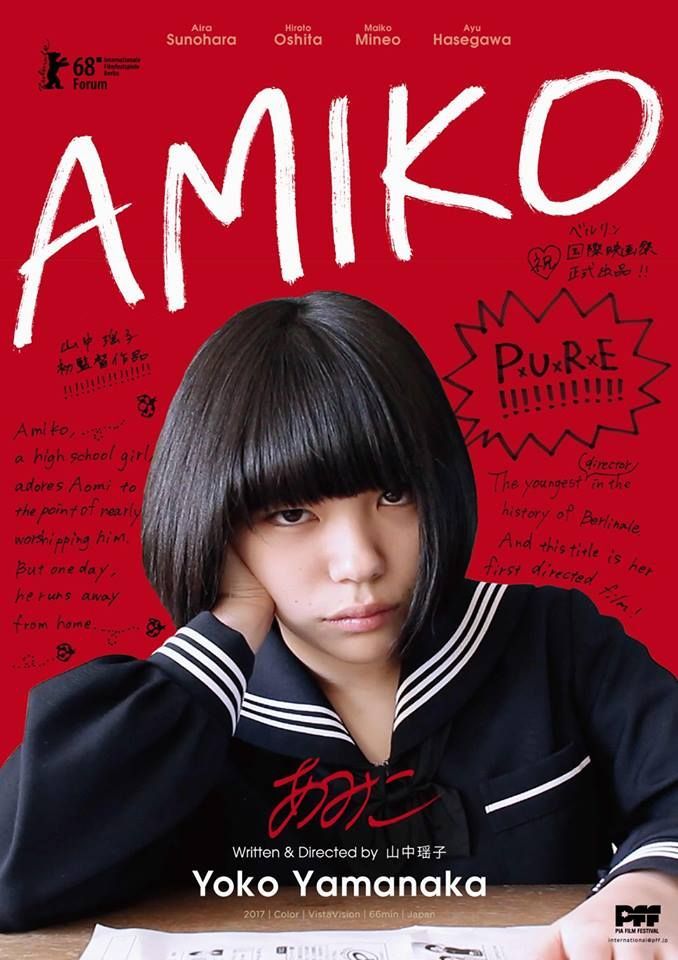

Some meetings are pivotal, others merely seem so. To melancholy high school girl Amiko (Aira Sunohara), consumed by youthful ennui and a sense of the long dull years stretching out before her, Aomi (Hiroto Oshita) seemed like some kind of heaven sent emissary – a good looking guy who seems to share her existential despair, her taste in music, and her lack of motivation for the business of living. Yet the meeting comes to nothing. After a single night of walking and talking, baring their souls and confessing their anxieties, the pair never talk again. Amiko continues to pine for Aomi, turning him into some kind of absent god, though months have passed with no real contact save her semi-stalking of him online. Eventually, almost a year later, Amiko learns that her one true love has deserted her and run off to Tokyo with another girl. Stunned, she resolves to follow him in the hope of finding out why he chose to renounce all it was she thought they meant to each other to embrace the mediocrity he once claimed to hate.

Some meetings are pivotal, others merely seem so. To melancholy high school girl Amiko (Aira Sunohara), consumed by youthful ennui and a sense of the long dull years stretching out before her, Aomi (Hiroto Oshita) seemed like some kind of heaven sent emissary – a good looking guy who seems to share her existential despair, her taste in music, and her lack of motivation for the business of living. Yet the meeting comes to nothing. After a single night of walking and talking, baring their souls and confessing their anxieties, the pair never talk again. Amiko continues to pine for Aomi, turning him into some kind of absent god, though months have passed with no real contact save her semi-stalking of him online. Eventually, almost a year later, Amiko learns that her one true love has deserted her and run off to Tokyo with another girl. Stunned, she resolves to follow him in the hope of finding out why he chose to renounce all it was she thought they meant to each other to embrace the mediocrity he once claimed to hate.

Amiko is not completely alone, she has a best friend – Kanako (Maiko Mineo), though she confesses that deep down they don’t really understand each other. Aomi too seems to think that Kanako is closed off, not really trusting anyone and living a superficial life. Nevertheless, Kanako does at least provide Amiko with the opportunity to experience the regular high school girl world of gossiping about boys on the telephone and silently resenting other, more popular girls. Claiming that “ordinary poor souls” could never understand the innate connection between herself an Aomi, Amiko decides to keep her long night walk of the soul a secret from her best friend in order to secure its purity.

Amiko, based on their intimate conversation, is convinced that Aomi feels the same way she does, understands her intense sense of existential despair, and is just as bored and disconnected as she feels herself to be. Confessing that he doesn’t actually like sports, in fact he hates being outside, Aomi offers the excuse that it’s easier being told what to do than trying to figure things out on your own. Carried along by the fact he’s good at football and can’t quite find the energy to protest, Aomi drifts on a cloud of his own apathy – one of the cool set of handsome and aloof high school boys popular with those who like unattainable guys. Like Amiko he likes “deep” music, instantly recognising the Radiohead track on her phone, but eventually runs off with the kind of girl Amiko (not so) secretly despises – an airhead popular girl and the “embodiment of mass culture”.

Aomi’s betrayal isn’t just romantic heartbreak, but the severing of a spiritual connection which never really existed in the first place. Rather than deepen the engagement, Amiko opts to leave her night of connection as a mythic encounter, sanctified by its unique quality. Aomi therefore becomes a mythic figure, a composite of Amiko’s various projections of her ideal soulmate, mirroring her own sense of ideological purity. Her new god, however has feet of clay and after tracking him down in the city she’s forced to confront the distance between the image and the reality. Was their connection as real as she thought it was, or only superficial musing on a cool crisp night when there was nothing much else to do?

Deep into her teenage apathy, Amiko talks about those manic, one off days where you just might find yourself doing something crazy out of a sense of cosmic despair. Aomi puts this idea back on the table as a possible motive for his abrupt flight to the city, and Amiko’s random pursuit of him is perhaps its aftershock. Wandering around having mad adventures – joining in with a madman’s (Hisato Takahashi) condemnation of a world of lies and the non-existence of real love, testing the ability of Japanese people to dance spontaneously, and stalking Aomi’s girlfriend, Amiko begins to accept that she may have been mistaken in placing such cosmic importance on what may just have been an inconsequential night filled with accidental profundity. Preferring to maintain the “purity” of her ideal, Amiko remains trapped within her own sense of despair but with a new sense of clarity and a determination not to let the phoniness of the world destroy her essential self.

Amiko was screened as part of Fantasia International Film Festival 2018.

Original trailer (no subtitles)