Kokoro isn’t “lying” when she complains of a stomach ache to avoid going to school, it’s just that it’s the anxiety she feels at the prospect that is making her physically ill. Based on a novel by Mizuki Tsujimura, Keiichi Hara’s fantasy-infused anime Lonely Castle in the Mirror (かがみの孤城, Kagami no Kojo) explores the effects of school phobia in uniting a series of teenagers who each for one reason or another have turned away from education often because of bullying or the rigidity of the contemporary schools system.

As we discover, Kokoro (Ami Toma) gradually stopped going to school after her life was made a misery by manipulative popular girl Sanada who operates a small clique of bullying minions yet appears all sweetness and light with the teaching staff. Unable to fully explain what’s been going on, Kokoro largely remains at home while her understanding mother (Kumiko Aso) explores opportunities in alternative teaching and tries to support her as best she can. Though the film is very sympathetic towards Kokoro and the children in insisting that it isn’t their fault they can’t attend school but the fault of an unaccommodating system, it perhaps misses an opportunity to fully commit to educational diversity when the end goal becomes getting Koroko back in class undaunted by the presence of her bully.

Nevertheless, it offers her another outlet when the mirror in her bedroom suddenly becomes a magic portal that transports her to a fantasy fairytale castle where she meets six other school phobic teens who are all dealing with similar issues. A young girl in wolf mask informs her that they have until the end of the school year to locate a key which if turned will grant one, but only one, of their wishes. When the key is turned, they will all lose their memory so it’s unclear if they will know whether or not the wish was granted but in any case are left with a choice between achieving their dreams and the new friendships they’ve formed at the castle. The issues that plague each of them are various from bullying to dealing with grief, purposelessness, a feeling of not fitting in, parental expectations, and an implication of sexual abuse at the hands of a close relative. As the Wolf Queen tells them “collaboration is beautiful” and it is the connections they forge with each other that give them strength to go back out into the world while each vowing to pay it forward and make sure to stand up to injustice by protecting other vulnerable kids like themselves when they’re able to.

Even so, Kokoro takes her time on even deciding whether or not to use the mirror and for some reason the castle is only open business hours Japan time. If they stay past five they’ll be eaten by wolves! Many things about the fantasy land do not add up and Kokoro begins to worry that it’s all taking place in her head, her new friends aren’t really real, and she’s being driven out of her mind by the stress of being the victim of a campaign of harassment she can’t even escape by staying home minding her own business. But through her experiences she is finally able to gain the courage to speak out against her bullying while supported by her steadfast mother and an earnest teacher who is keen to find the best solution for each of her pupils rather than trying to force them back into a one size fits all educational system.

In any case, Kokoro’s quest is to find her way back through the looking glass to rediscover her sense of self and take her place in mainstream society free of the sense of loneliness and inferiority she had felt while being bullied by Sanada and her clique of popular girls though in an ironic touch the film does not extend the same empathy to her or ask why Sanada has an apparent need to need to pick a target to destroy. A variable animation quality and occasional clash of styles sometimes frustrate what is at heart a poignant tale of finding strength in solidarity and learning to take care of each other in a world powered more by compassion than an unthinking devotion to the status quo.

Lonely Castle in the Mirror screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

International trailer (English subtitles)

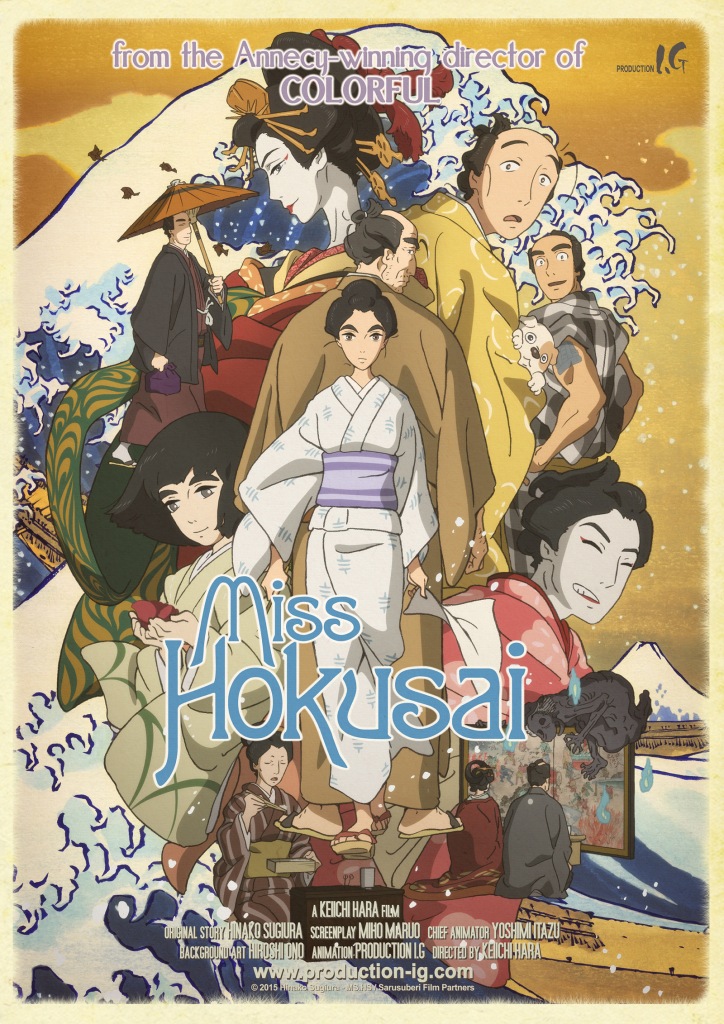

When it comes to the great Japanese artworks that everybody knows, the figure of Hokusai looms large. From the ubiquitous The Great Wave off Kanagawa to the infamous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the work of Hokusai has come to represent the art of Edo woodblocks almost single handedly in the popular imagination yet there has long been scholarly debate about the true artist behind some of the pieces which are attributed to his name. Hokusai had a daughter – uniquely gifted, perhaps even surpassing the skills of her father, O-Ei was a talented artist in her own right as well as her father’s assistant and caregiver in his old age.

When it comes to the great Japanese artworks that everybody knows, the figure of Hokusai looms large. From the ubiquitous The Great Wave off Kanagawa to the infamous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the work of Hokusai has come to represent the art of Edo woodblocks almost single handedly in the popular imagination yet there has long been scholarly debate about the true artist behind some of the pieces which are attributed to his name. Hokusai had a daughter – uniquely gifted, perhaps even surpassing the skills of her father, O-Ei was a talented artist in her own right as well as her father’s assistant and caregiver in his old age.