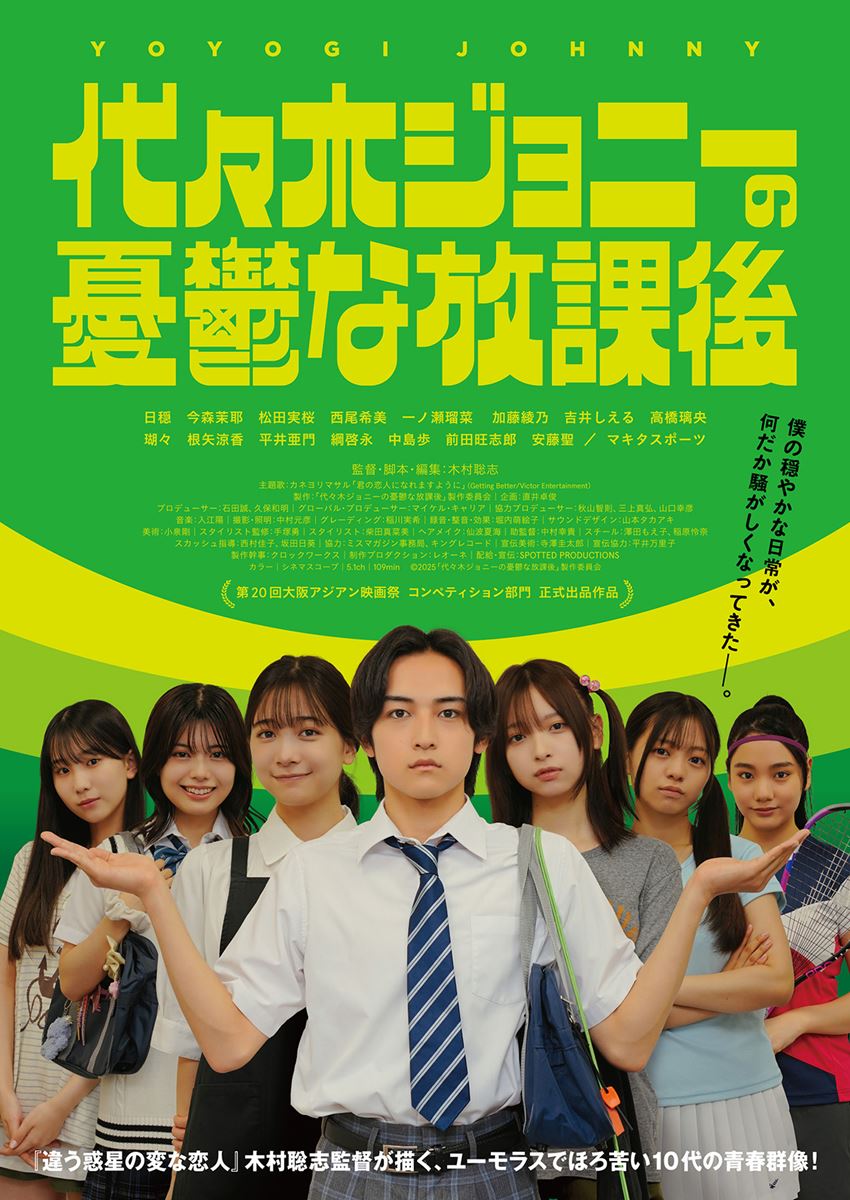

Not much makes a lot of sense in the world of the titular Yoyogi Johnny. Nothing’s quite as it first seems and life is full of contradictions, but that’s alright, for the most part. Johnny just floats on through life going with the flow, but then he meets a series of girls who each for some reason want to practice things with him though for very different reasons while he tries to make sense of it all and gain the courage to push for what he really wants.

Then again, he breaks up with Asako (Mio Matsuda) because he realises he likes her in the same way he likes “history” which is to say, when someone asks him what his favourite subject is he just says that but doesn’t actually know if he even likes history or not. Having never been in love, he doesn’t know what it’s like and therefore wants to end the relationship. Mostly he just spends his time hanging out in the “squash club” where they don’t actually play any squash but just use the clubroom to hideout from the less satisfying aspects of their lives or otherwise avoid other people. In fact, they’re only in the squash club to make up the numbers and were all looking to start clubs of their own but for various reasons were prevented from doing so. But when a mysterious young woman they christen Deko (Shieru Yoshii) for her prominent forehead arrives at the club looking for the founder, Ondera, whom they call “Button”, it wrecks their peaceful lives because of her insistence that they actually play some squash.

Deko wants to practice squash with him, but his childhood friend Kagura (Runa Ichinose) wants him to role play real world interactions while she has otherwise become a virtual recluse who no longer attends school. Meanwhile, he’s also drawn to a colleague at his part-time job at a bookshop/bar, Izumo (Maya Imamori), who is also the boss’ daughter. Somewhat salaciously, she wants him to practice “physical contact,” as that’s one of the areas she has difficulty in having herself also been a recluse who dropped out of school and has come to Tokyo for a fresh start. Johnny immediately picks up on this irony of Izumo salmoning her way to the capital while, in general, most people are travelling away from the city to a less populated area for a quieter life rather than the other way around though like many of these conversations it’s lost on Izumo to whom it is of course just normal. Johnny has several of these conversations in which he attempts to point out that something doesn’t make sense but just finds himself trapped in an infinite loop of back and fore as the other person struggles to understand his logic or he theirs. He is however a kind person who tries to help everyone who asks him though perhaps without really thinking about it.

Yet most of the young women eventually oscillate out of his life depriving him of these very important friendships and ironically rebounding to the squash club even though they now actually have to play squash. Nevertheless, through his various relationships Johnny begins to gain a new perspective on himself and even finds out what it’s like to fall in love. A strange young woman who seems to be part of what very much looks like a cult, reminds him that “self-sufficiency” is a lie even though it’s supposedly what their cult is founded on. It is after all an organisation that promotes “independent living” while sending its members who all live in the dorm to farm the fields, though this yet another thing that doesn’t really make sense but Johnny just has to accept. Nevertheless, it seems she’s right when she says people can’t live by themselves alone and by and large need each other to survive. She tells Johnny that he should stop visiting Kagura because it’s “meaningless” and wouldn’t help her, but at the same time seems to appreciate his good-naturedness and the gentle positivity he puts out into the world in his ability to just be nice and be there for that want or need him while never expecting anything in return. As he’s fond of saying, if you regard a person as a friend then it doesn’t really matter whether they agree or not they’re still your friend and Johnny has more than many might awesome he would. Warm-hearted and filled zany humour, the retro aesthetic of its opening titles only adds to film’s charm as a little gem of indie comedy.

Yoyogi Johnny screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Trailer (no subtitles)