“A man has his code” a late villain explains in King Hu’s radical Buddhist wuxia epic, A Touch of Zen (俠女, Xiá Nǚ), justifying his villainy with weary fatalism as a matter dictated by the world in which he lives and of which he is merely a passive conduit. Based on a story by Pu Songling, Hu’s meandering tale begins as gothic horror yet ends in enlightenment parable that in itself reflects the values of Jianghu as a warrior monk achieves nirvana in the apotheosis of his righteousness.

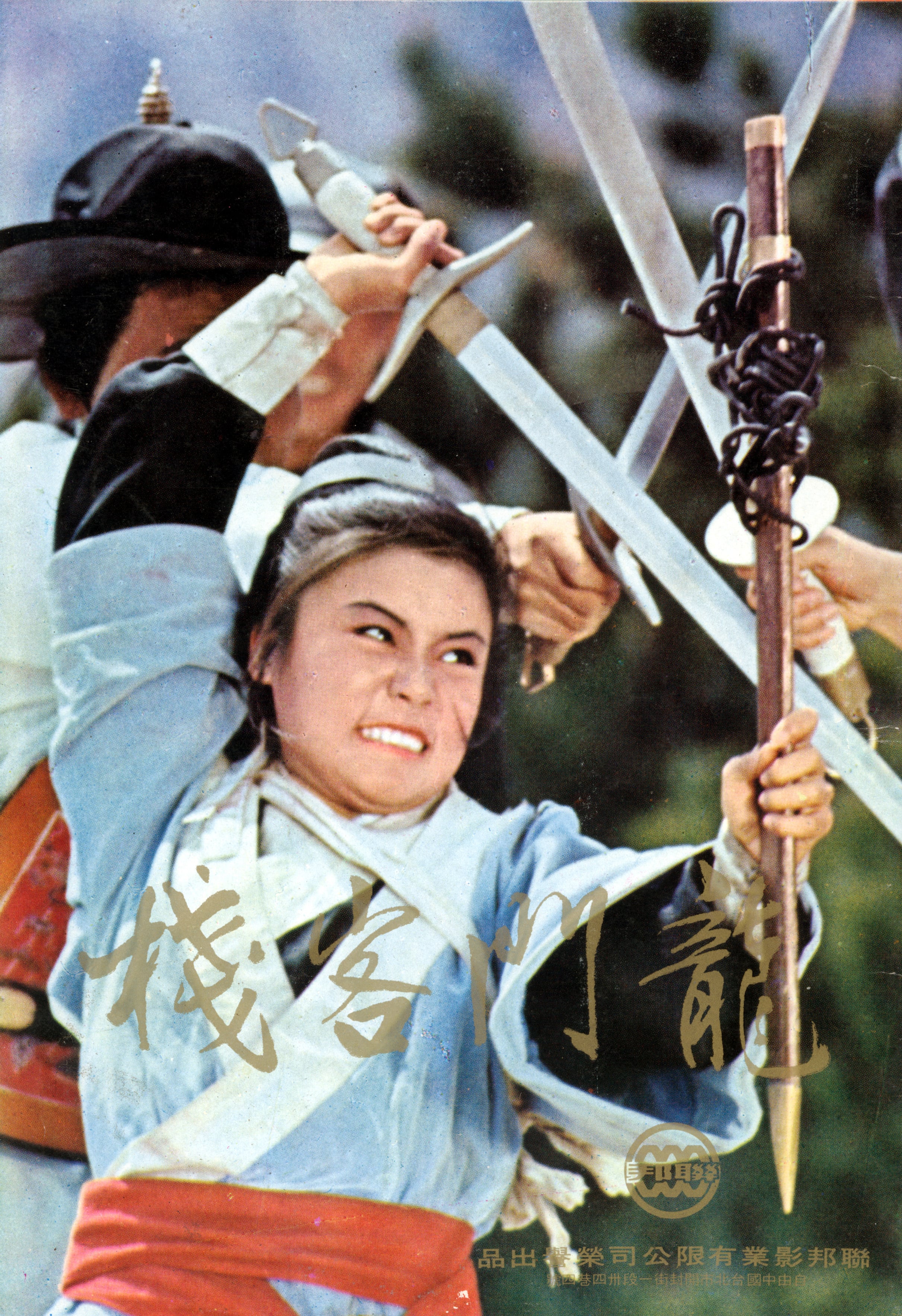

Hu begins however with slowly mounting tension as lackadaisical scholar Gu Shengzhai (Shih Chun) begins to notice something strange going on in the sleepy rural backwater where he lives. There are several strangers in town from the recently arrived pharmacist Dr Lu (Xue Han), to the blind fortune teller Shi (Bai Ying), and a young man who stops into his shop to have a portrait done (Tien Peng) but is behaving somewhat suspiciously. Shengzhai has also noticed unexpected activity at a house opposite his long thought to be “haunted”, activity which turns out to be caused by a young woman, Miss Yang (Hsu Feng), living in penury with her bedridden mother.

Shengzhai is often described as feckless or immature, his mother (Zhang Bing-yu) constantly complaining that he refuses to take the civil service exam and has stubbornly wasted his life with “pointless” study while they live harsh lives with little comfort. Shengzhai is, however, an unconventional jianghu hero who has rejected a world of courtly corruption in order to live by his own principles even if that means a poor but honest existence. In a sense he becomes a man through his brief relationship with Yang who turns out to be a noblewoman on the run from the East Chamber after being sentenced to death because of her father’s attempt to expose the corruption of a high ranking eunuch. After he and Yang enjoy a single night of passion in the middle of a thunderstorm, Shengzhai becomes determined to protect her and reveals he has spent much of his life studying military strategy, but he also fully accepts Yang’s agency and right dictate her future walking back his claim of feeling duty-bound because they are “almost married” to be content to help “even as a friend”.

Nevertheless, there is something of boyish glee in the machinations of his trickery, repurposing the gothic horror of the “haunted” fort as a means to “demoralise” the enemy. His second antagonist, Men Da (Wang Rui), refuses to take the rumours, ably spread by Shengzhai’s gossipy mother panel to panel through a series of expanding split screens, seriously describing them as something only “ignorant country folk” would believe but later falls victims to Shengzhai’s elaborate setup. After his victory, Shengzhai walks through the fort laughing his head off playing with the lifeless mannequins he positioned as ghosts and idly tapping various traps and mechanisms, but it’s not until he leaves the ruined building and ventures outside that he realises the true cost of his childish game in the rows of bodies stretching out and around before realising Yang is nowhere to be found. Shengzhai becomes a man again, forced to accept the consequences of his actions, but also defiant, ignoring advice and instruction on leaving home in search of a woman who asked him not to look for her.

As he later discovers, Yang and her retainer have renounced the world for a monastic life returning to the Buddhist temple in which Yang learned martial arts during her two years of exile under the all powerful master Hui Yuan (Roy Chiao) who is now it seems close to achieving enlightenment though that won’t stop him helping Yang deal with her “unfinished business”. Like the heroes of jianghu, Yang removes herself from a world of infinite corruption though in this case to pursue spiritual enlightenment and thereafter forgoes her revenge, acting in defence only rather striking back at Eunuch Wei or the East Chamber. At the film’s conclusion, Hui Yang’s act of compassion brings about his betrayal but through it his enlightenment. Struck, he bleeds gold blood and sits atop a rocky outcrop as the sun radiates around his head in a clear evocation of his transcendence witnessed at a distance even by Shengzhai alone and placed once again in a traditionally feminine role literally left holding the baby but perhaps freed from the web of intrigue in which he had been trapped spun all around him just like that weaved by the spider in the film’s gothic opening.

Stunningly capturing the beauty of the Taiwanese countryside with its ethereal rolling mists and sunlit forests, Hu’s composition takes on the aesthetic of a classic ink painting finding Shengzhai lost amid the towering landscape while eventually veering into the realms of the experimental in the transcendent red-tinted negative of spiritual transition. For Hu’s jianghu refugees, there can be no victory in violence only in the gradual path towards enlightenment born of true righteousness and human compassion.

A Touch of Zen streams in the US until Sept. 28 as part of the 13th Season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

International restoration trailer (English subtitles)