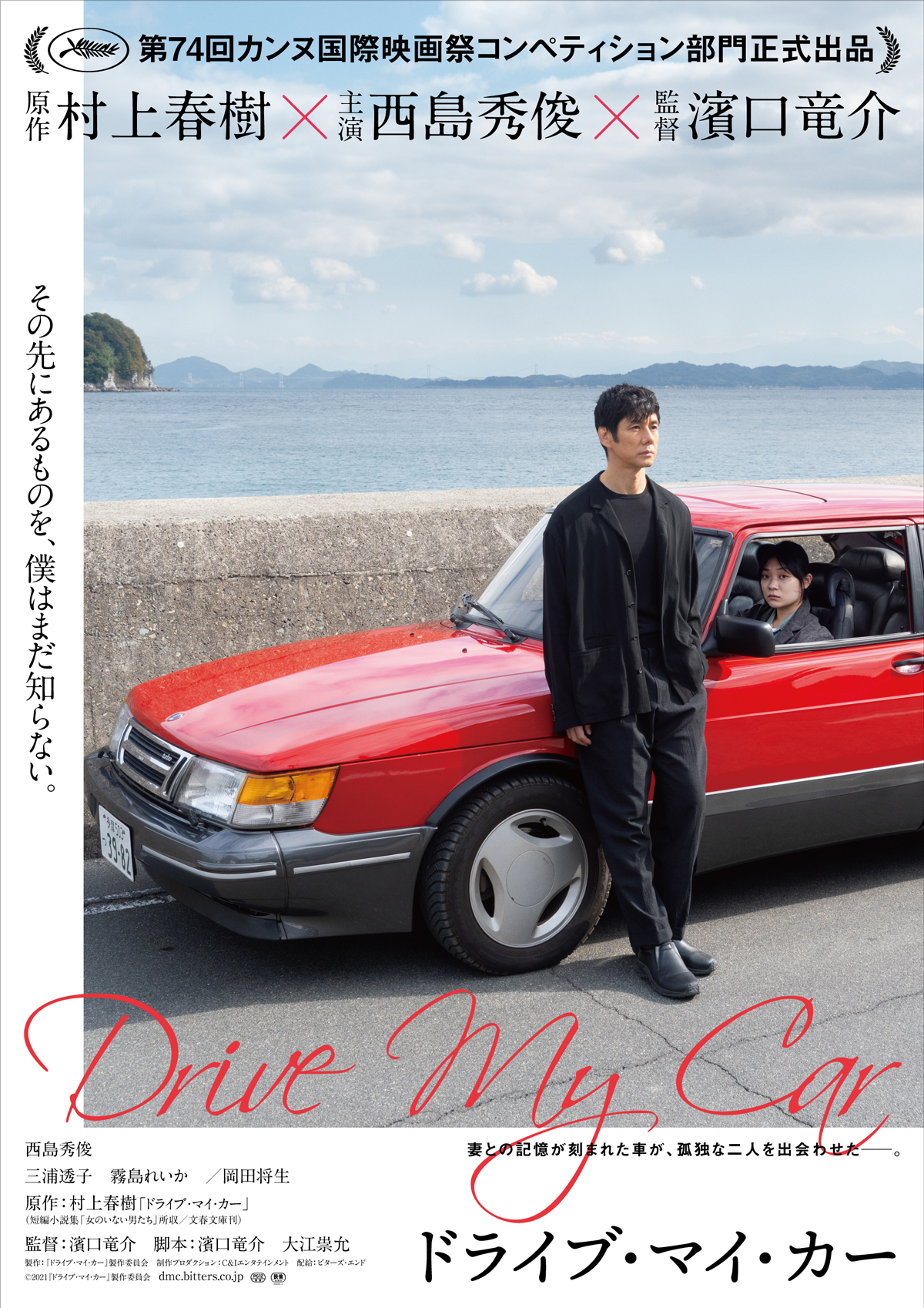

“What can we do? we must live our lives” comes a constant refrain echoing the closing words of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya offered by the self-sacrificing Sonya resolving to find joy in suffering if only in the promise of a better world to come. Freely adapted from a short story by Haruki Murakami, Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s profoundly moving Drive My Car (ドライブ・マイ・カー) is study in grief, loss, and how you learn to live after the world has ended but also of how we pull each through, finding new ways to communicate when words alone can’t help us.

Words are, however, where we begin with a woman half in shadow an accidental Scheherazade spinning a bizarre tale of a high school girl’s first love. Oto (Reika Kirishima) claims the story is not about her, but as we’ll later discover in some ways it is if perhaps not literally. A long-married couple, this is part of their marital routine, screenwriter Oto telling stories to her theatre director husband Yusuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima) she asks him to remember and repeat back to her in the morning. Only one day, having accidentally stumbled in on his wife and her lover only to leave quietly saying nothing, Yusuke claims not to remember. She tells him she wants to talk, but he is afraid of what she’ll say and delays coming home, finding her collapsed in the hallway on his return having passed away from a cerebral haemorrhage. The story remains incomplete, a perpetual cliffhanger never to be resolved.

Two years later Yusuke is a haunted man still listening to the cassette tape Oto left for him of her reading all of the other lines of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya save for those of the title character which he was to play himself. This time he’s been selected as an artist in residence at at a theatre in Hiroshima where he’ll once again stage Vanya in his signature multilingual performance style. He’s specifically asked for accommodation an hour’s drive away with the intention of maintaining his usual routine of listening to the tape on his way to rehearsal but, following previous incidents, the theatre has a policy of hiring their own drivers in this case a young woman, Misaki (Toko Miura), who eventually wins him over through her capability and care while, ironically, mimicking the very qualities he demands of his actors in her wounded stoicism.

The car in a sense represents an inviolable space of intimacy, a space that Yusuke had been reluctant to allow anyone to enter, even Oto remarking on his discomfort with her in the driver’s seat as she took him to a doctor’s appointment where he learned he was losing the sight in his left eye, clarifying with the doctor that for the time being at least he’d be OK to drive himself. Misaki assumes he doesn’t want her to drive his car because she’s a young woman, but thereafter is careful to maintain distance respecting his space for her sake as much as his own mindful of her role as a “driver” until he begins to invite her in if originally more out of politeness or consideration than a desire for company.

Misaki has her own story, a story she too is originally reluctant to share but in its way echoes his as someone trapped in grief and guilt ironically unable to move forward but driven by the quality of Oto’s voice and the ritualistic call and response implied by its lacunas. Too afraid of its implications to take the role himself, Yusuke casts Oto’s lover, Takatsuki (Masaki Okada) a young TV actor with impulse control issues whose career has apparently been ruined by scandal, as Vanya a man approaching 50 whose illusions are painfully shattered, forcing him to realise that he’s wasted his life on a futile ideal. The three of them, each eventually entering the confessional space of the car, share more than they might assume but it’s Takatsuki who holds the key revealing another piece of the puzzle with unexpected profundity that in its own way lays bare a truth Yusuke had been unwilling to see about his relationship with his wife, the shared grief that both bound and divided them, and the poetic import of her death.

Rather than Vanya, the film’s prologue saw Yusuke perform in a multilingual production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the author’s well-known phrase “I must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on” perhaps equally apt even as Yusuke moves slowly away from the role of Vanya before finally assuming that of Sonya in echoing her words while comforting the filial figure of Misaki even as she explains to him that as in Vanya the fault was not in his convictions but in himself that he couldn’t accept the contradictions of his wife and in that sense had not understood her or himself well enough to know he should have braved the hurt of confrontation. Yet as Takatsuki had said, you can’t ever really know another person, there’s always a part of them forever out of reach all you can do is try to make peace with your own darkness.

For Yusuke communication occurs indirectly, through allegory or half-truth, and through the unspoken or unintelligible. His multilingual approach in which lines are read coldly at half-speed is intended to draw out the feeling that lies beneath them, the final most profound moment delivered in silence as a former dancer breaking free of her bodily inertia delivers Sonia’s closing monologue with all of its melancholy serenity in Korean sign language her arms draped angelically over Vanya’s shoulders in a gesture of the utmost comfort. Touching in its ambiguities, Hamaguchi’s quietly devastating emotional drama for all of its eerie uncanniness finally places its faith in simple human empathy as its haunted souls learn to live with loss finding in each other the strength to go on living.

Drive My Car screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

The

The