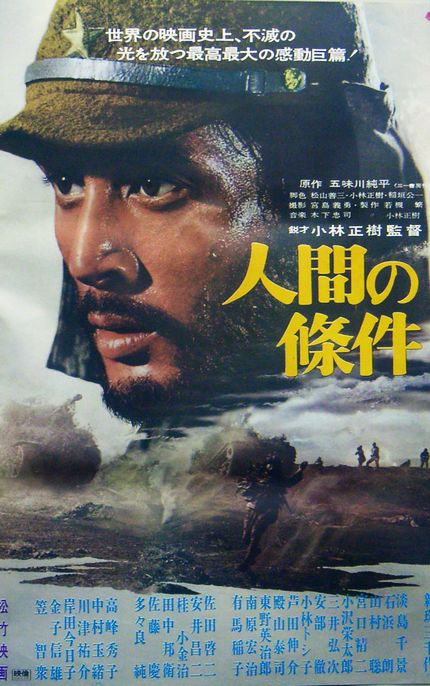

Review of Masaki Kobayashi’s magnum opus The Human Condition (人間の條件, Ningen no Joken) first published by UK Anime Network

If Masaki Kobayashi had an overriding concern throughout his career, it was the place of the conflicted soul within an immoral society. Nowhere is this better articulated than in his masterwork – the nine and a half hour epic, The Human Condition. Adapted from a novel by Junpei Gomikawa, Kobayashi’s film also mirrors his own wartime experiences which saw him conscripted into the army and sent to Manchuria where he was accounted a good soldier, but chose to mark his resistance to the war effort by repeatedly refusing all promotions above the rank of Private. Kaji, by contrast, essentially sells his soul to the devil in return for a military exemption so that he can marry his girlfriend free of the guilt that comes with dragging her into his uncertain future. At this point Kaji can still kid himself into thinking he can change the system from within but to do so means compromising himself even further.

The first of three acts, No Greater Love, takes place in Manchuria during the Japanese expansion where Kaji is working for a Japanese steel company. Fully aware that the company is using forced and exploitative labour, Kaji has been tasked with increasing productivity and has written a comprehensive report indicating that introducing better working conditions would positively affect efficiency as there would be less absenteeism and fewer sickness related gaps in the line. His boss is impressed and presents him with an offer of promotion managing a mine in the North. Kaji is conflicted but ultimately decides to accept as the post comes with a certificate of military exemption so he can finally marry his girlfriend, Michiko. However, his progressive ideals largely fall on deaf ears.

Road to Eternity finds him in the army where his left leaning ideas are even less appreciated than they were at the mine. Asked to train recruits, Kaji once again enacts a progressive approach which takes physical reinforcement out of the process and focusses on building bonds between men but his final battle comes too early leaving his team dangerously exposed. Kaji is briefly reunited with Michiko who has made a perilous journey to visit him but neither of the pair knows when or if they will see each other again.

The concluding part, A Soldier’s Prayer, finds a defeated Kaji wandering the arid land of Northern Manchuria on a desperate quest south with only the thought of getting back home to Michiko keeping him going. Eventually he is taken prisoner by Soviet forces but far from the people’s paradise he’d come to believe in, the Russians are just as unforgiving as his own Japanese. In the army he was a “filthy red” but now he’s a “fascist samurai”.

As much as Kaji is “good” man filled with humanistic ideals, he is also an incredibly flawed central presence. Already compromised by working for the steel company in Manchuria in the first place fully knowing the way the company behaves in China, his decision to take the mining job is an act of self interest in which he trades a little more of his integrity for military exemption and a marriage license. Needless to say, the head honchos at the mine who’ve been at the coal face all along do not take kindly to this baby faced suit from head office suddenly showing up and telling them they’ve been doing everything wrong. Far from listening to their experiences and arguing his point, Kaji attempts to simply overrule the mining staff taking little account of the already in place complex inter-office politics. This creates a series of radiating factions, most of whom side with Kaji’s rival and have come to view the cruel treatment of workers as a sort of office perk.

The complicity only deepens as Kaji becomes ever more a part of the machine. Kaji feels distraught after he loses his temper and strikes a subordinate, but before long he’s physically whipping a crowd of starving men in an attempt to stop them killing themselves through overeating. His biggest crisis comes when a number of Chinese prisoners are caught trying to escape and Kaji is unable to help them after specifically guaranteeing nobody would be killed. Forced to watch the botched execution of a brave man who refused to capitulate even at the end, Kaji is forced to acknowledge his own role in the deaths of these men, his complicity in the ongoing system of abuse, and his complete powerlessness to effect any kind of change in attitudes among the imperialist diehards all around him.

Kobayashi pulls no punches when it comes to examining the recent past. The steel company is built entirely on the exploitation of local workers who are progressively stripped of their humanity, whipped and beaten, starved and humiliated. The situation is only made worse when Kaji is forced to accept a number of “special labourers” from the military police. Tagged as prisoners of war, these men are not soldiers but displaced locals from Northern villages razed by Japanese troops. The train they arrive on is worse than a cattle truck and some of the men are already dead of heat, thirst, and starvation. The others pour out, zombie-like, searching desperately for food and water. Kaji is further compromised when the head of the mine has a plan of his own to subdue the men which involves procuring a number of comfort women which Kaji eventually does even if the entire process makes him sick. This is where the system has brought him – effectively to the level of a people trafficker, pimping vulnerable women to enslaved men.

Kaji comes to believe in a better life across the border where people are treated like human beings but anyone who’s read ahead in the textbooks will know this doesn’t work out for him either. Equally scathing about the left as of the right, The Human Condition has very little good to say about people, especially when people begin to act as a group. Even Kaji himself who has so many high ideals is brought low precisely because of his self-centred didacticism which makes it impossible for him to take other people’s views into account. With his faith well and truly smashed, Kaji has only the vague image of Michiko to cling to. Even so, he trudges on alone through the snowy landscape, deluded by hope, still dreaming of home. Trudging on endlessly, driven only by blind faith, perhaps that’s the best definition of the human condition that can be offered. A brutal exercise in soul searching, The Human Condition is not always even certain that it finds one but still retains the desire to believe in something better, however little in evidence it may be.

Trailers for each of the three parts (English subtitles)

The best revenge is living well, but the three damaged individuals at the centre of Tomoyuki Takimoto’s Grasshopper (グラスホッパー) might need some space before they can figure that out. Reuniting with

The best revenge is living well, but the three damaged individuals at the centre of Tomoyuki Takimoto’s Grasshopper (グラスホッパー) might need some space before they can figure that out. Reuniting with

A Double Life (二重生活, Nijyuu Seikatsu ), the debut feature from director Yoshiyuki Kishi adapted from Mariko Koike’s novel, could easily be subtitled “a defence of stalking with indifference”. As a philosophical experiment in itself, it recasts us as the voyeur, watching her watching him, following our oblivious heroine as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the act of observance. Taking into account the constant watchfulness of modern society, A Double Life has some serious questions to ask not only of the nature of existence but of the increasing connectedness and its counterpart of isolation, the disconnect between the image and reality, and how much the hidden facets of people’s lives define their essential personality.

A Double Life (二重生活, Nijyuu Seikatsu ), the debut feature from director Yoshiyuki Kishi adapted from Mariko Koike’s novel, could easily be subtitled “a defence of stalking with indifference”. As a philosophical experiment in itself, it recasts us as the voyeur, watching her watching him, following our oblivious heroine as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the act of observance. Taking into account the constant watchfulness of modern society, A Double Life has some serious questions to ask not only of the nature of existence but of the increasing connectedness and its counterpart of isolation, the disconnect between the image and reality, and how much the hidden facets of people’s lives define their essential personality. Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance.

Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance.

Loosely based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (Satanism and Witchcraft) which reframed the idea of the witch as a revolutionary opposition to the oppression of the feudalistic system and the intense religiosity of the Catholic church, Belladonna of Sadness (哀しみのベラドンナ, Kanashimi no Belladonna) was, shall we say, under appreciated at the time of its original release even being credited with the eventual bankruptcy of its production studio. Begun as the third in the Animerama trilogy of adult orientated animations produced by legendary manga artist Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, Belladonna of Sadness is the only one of the three with which Tezuka was not directly involved owing to having left the company to return to manga. Consequently the animation sheds his characteristic character designs for something more akin to Art Nouveau elegance mixed with countercultural psychedelia and pink film compositions. Feminist rape revenge fairytale or an exploitative exploration of the “demonic” nature of female sexuality and empowerment, Belladonna of Sadness is not an easily forgettable experience.

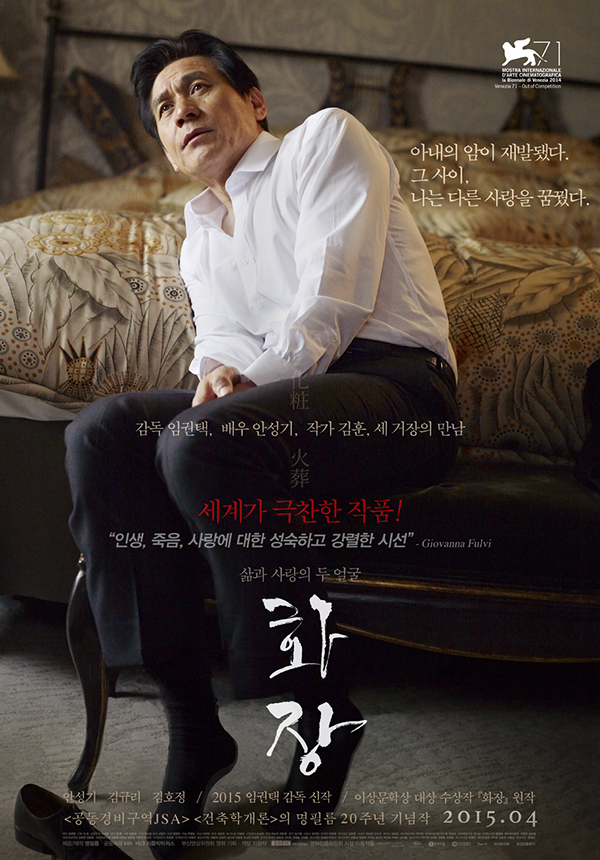

Loosely based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (Satanism and Witchcraft) which reframed the idea of the witch as a revolutionary opposition to the oppression of the feudalistic system and the intense religiosity of the Catholic church, Belladonna of Sadness (哀しみのベラドンナ, Kanashimi no Belladonna) was, shall we say, under appreciated at the time of its original release even being credited with the eventual bankruptcy of its production studio. Begun as the third in the Animerama trilogy of adult orientated animations produced by legendary manga artist Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, Belladonna of Sadness is the only one of the three with which Tezuka was not directly involved owing to having left the company to return to manga. Consequently the animation sheds his characteristic character designs for something more akin to Art Nouveau elegance mixed with countercultural psychedelia and pink film compositions. Feminist rape revenge fairytale or an exploitative exploration of the “demonic” nature of female sexuality and empowerment, Belladonna of Sadness is not an easily forgettable experience. The 102nd film from veteran Korean film director Im Kwon-taek may appear close to the bone in its depictions death, suffering, and the long look back on a life filled with the quiet kind of love but Revivre (화장, Hwajang) is anything but afraid to ask the questions most would not want to hear as the light dwindles. The inner journey is just too hazy, as one man puts it, unknowingly commenting on the human condition, yet Im does manage bring us nicely into focus, if only for a moment.

The 102nd film from veteran Korean film director Im Kwon-taek may appear close to the bone in its depictions death, suffering, and the long look back on a life filled with the quiet kind of love but Revivre (화장, Hwajang) is anything but afraid to ask the questions most would not want to hear as the light dwindles. The inner journey is just too hazy, as one man puts it, unknowingly commenting on the human condition, yet Im does manage bring us nicely into focus, if only for a moment.

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process.

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process. Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own.

Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own. Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.