Japan was in a precarious position in 1937. Ozu’s What Did the Lady Forget? (淑女は何を忘れたか, Shukujo wa Nani wo Wasureta ka) was released in March of that year but by July the Second Sino-Japanese War would be in full swing and on the home front increasing censorship would render this kind of inconsequential comedy a much less easy sell. True enough, the film includes no “patriotic” content though it does eventually reinforce a set of patriarchal values in the remasculinisation of a henpecked husband while quietly sniggering at a new bourgeois social class.

The drama unfolds in the home of a medical professor, Komiya (Tatsuo Saito), and his austere wife Tokiko (Sumiko Kurishima). The couple have no children and mostly lead separate lives. Tokiko spends her days with two close friends, widowed single-mother Mitsuko (Mitsuko Yoshikawa), and wealthy older woman Chiyoko (Choko Iida) who is married to her husband’s friend, Sugiyama (Takeshi Sakamoto). The three women gossip about the usual things from fancy department store kimonos to new ways to laugh so you don’t get wrinkles along with the bizarrely difficult maths problems Mitsuko’s son has been studying in preparation for middle-school that none of them can answer. To help with the embarrassingly taxing homework, Tokiko offers to find a tutor, press-ganging her husband’s best student, Okada (Shuji Sano), into spending time with Mitsuko’s son Fujio (Masao Hayama) though it turns out that he too, a college graduate, is unable to solve these middle-school level problems.

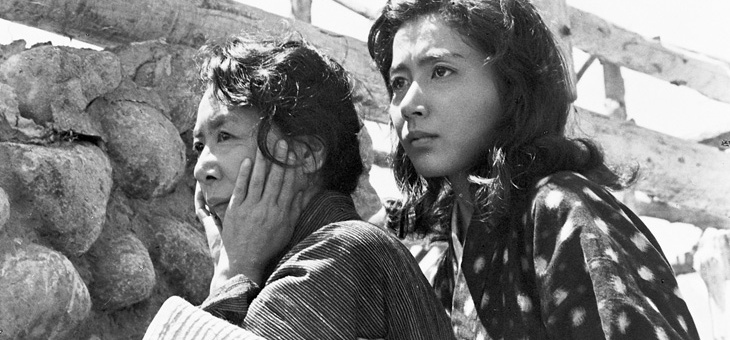

The real drama occurs when the couple’s neice, Setsuko (Michiko Kuwano), whom Tokiko had described as “proper” and “wholesome” rocks up from Osaka having become the epitome of a modern girl. Setsuko’s arrival further strains the Komiyas’ already fraying relationship as her surprising habits which include driving, smoking, drinking, and hanging out with geisha, continue to exasperate her aunt whose main objection to all of those things is that they aren’t appropriate because Setsuko is not yet married. To get away from his nagging wife who forces him to go golfing as usual when he doesn’t really want to, Komiya stashes his clubs with Okada and goes to a bar in Ginza where he meets Sugiyama who has also been forced outside by his wife. Sugiyama really does go golfing, promising to mail a previously written postcard to Tokiko on Komiya’s behalf, while he is eventually joined by Setsuko who has tracked him down to the bar despite being told to stay home and mind the house (the Komiyas have two live-in maids so the instruction seems unnecessary at best).

As a “modern gal” Setsuko has some strangely old fashioned ideas even as she behaves like a 1930s ladette, striding around like man while drinking, smoking, and generally being almost as intimidating as Tokiko just in a more likeable fashion. Setsuko finds Komiya’s deferral to his wife embarrassing, encouraging him to be more masculine and stand up for himself even advising that he use violence to reassert his position as the man of the house. He seems uncomfortable with the idea but eventually does just that after a climactic argument once his lying about the golf and Setsuko’s nighttime adventures have been exposed. Caught in a moment of frustration, he slaps Tokiko across the face, leaving her to retreat in shock apparently “beaten”. The thing is, however, Tokiko likes it. She sees his slapping her as a sign of his love, as if she’s been needling him all this time in hope of a reaction while frustrated that perhaps he doesn’t care for her. Once he hits her, the marriage is rebalanced and repaired with traditional gender dynamics restored. She becomes more cheerful and deferent to his male authority, he acknowledges that he enabled her “arrogance” with his weakness as a man.

Setsuko however, continues to shout at her uncle, disappointed that he apologised for his reaction and accusing him of giving away the victory he’d just won. He tells her that he’s simply using reverse psychology because wives like to believe they’re in charge and in the main it’s best to let them. Setsuko seems satisfied, but jokes with her new love interest Okada that he better not use reverse psychology on her. Or, he can, but she’ll just use reverse reverse psychology to get the upper hand, which perhaps undercuts the central message in praise of traditional gender roles. Nevertheless, What Did the Lady Forget? is full of Lubitschy late-30s charms from an unexpected sighting of real life star Ken Uehara at the Kabuki to Setsuko’s movie magazines featuring Marlene Dietrich and repeated references to Frederich March and William Powell proving that Ginza is open even in 1937, while the Komiya household descends into an oddly peaceful harmony of delayed marital bliss.

Currently streaming in the UK via BFI Player as part of Japan 2020. Also available to stream in the US via Criterion Channel.

Shimizu, strenuously avoiding comment on the current situation, retreats entirely from urban society for this 1941 effort, Introspection Tower (みかへりの塔, Mikaheri no Tou). Set entirely within the confines of a progressive reformatory for troubled children, the film does, however, praise the virtues popular at the time from self discipline to community mindedness and the ability to put the individual to one side in order for the group to prosper. These qualities are, of course, common to both the extreme left and extreme right and Shimizu is walking a tightrope here, strung up over a great chasm of political thought, but as usual he does so with a broad smile whilst sticking to his humanist values all the way.

Shimizu, strenuously avoiding comment on the current situation, retreats entirely from urban society for this 1941 effort, Introspection Tower (みかへりの塔, Mikaheri no Tou). Set entirely within the confines of a progressive reformatory for troubled children, the film does, however, praise the virtues popular at the time from self discipline to community mindedness and the ability to put the individual to one side in order for the group to prosper. These qualities are, of course, common to both the extreme left and extreme right and Shimizu is walking a tightrope here, strung up over a great chasm of political thought, but as usual he does so with a broad smile whilst sticking to his humanist values all the way. The well known Natsume Soseki novel, Botchan, tells the story of an arrogant, middle class Tokyoite who reluctantly accepts a teaching job at a rural school where he relentlessly mocks the locals’ funny accent and looks down on his oikish pupils all the while dreaming of his loyal family nanny. Hiroshi Shimizu’s Nobuko (信子) is almost an inverted picture of Soseki’s work as its titular heroine travels from the country to a posh girls’ boarding school bringing her country bumpkin accent and no nonsense attitude with her. Like Botchan, though for very different reasons, Nobuko also finds herself at odds with the school system but remains idealistic enough to recommend a positive change in the educational environment.

The well known Natsume Soseki novel, Botchan, tells the story of an arrogant, middle class Tokyoite who reluctantly accepts a teaching job at a rural school where he relentlessly mocks the locals’ funny accent and looks down on his oikish pupils all the while dreaming of his loyal family nanny. Hiroshi Shimizu’s Nobuko (信子) is almost an inverted picture of Soseki’s work as its titular heroine travels from the country to a posh girls’ boarding school bringing her country bumpkin accent and no nonsense attitude with her. Like Botchan, though for very different reasons, Nobuko also finds herself at odds with the school system but remains idealistic enough to recommend a positive change in the educational environment. Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance.

Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance.