The architecture professor teaching a young woman in Panu Aree and Kong Rithdee’s The Cursed Land (แดนสาป) says that a house is like a machine with a person inside, but what’s inside the house at the film’s centre is not quite human at all but a supernatural creature who like the house itself seems straddle a divide both cultural and spiritual while standing itself at the nexus of the many layered historical curses which have given it its dark legacy.

It’s in part a rejection of this difference and lack of respect for culture that creates a series of problems for Mit (Ananda Everingham), a middle-aged engineer moving into this rural backwater on the outskirts of Bangkok. Despite receiving a very serious warning to get rid of anything that’s in the house, he tears off a series of talismans thereby releasing some very dark energy and destabilising his new environment. Mit is also suspicious of those around him and does not really make much of an attempt to make friends with the local community who are largely Muslim. Though he may not think so, it is Mit who is the intruder here, an outsider walking into a traditional environment and finding himself isolated despite the ostensible friendliness of some of the locals to whom Mit takes offence after being told not to leave his dog outside because some of the Muslim community dislike them.

But then again, Mit also seems to be a compromised figure apparently still suffering from shock and confusion some time after a car accident that killed his wife. He complains that his medication has been misplaced due to the move while seemingly increasingly paranoid and unreasonable. We also get hints that Mit’s previous life may not have been plain sailing either and part of his stress is down to a need to prove himself in his new job. He is in his way haunted by the car accident and struggling to overcome his guilt and regret. A shamaness later describes him as “weak-minded” and therefore a prime target for an evil spirit.

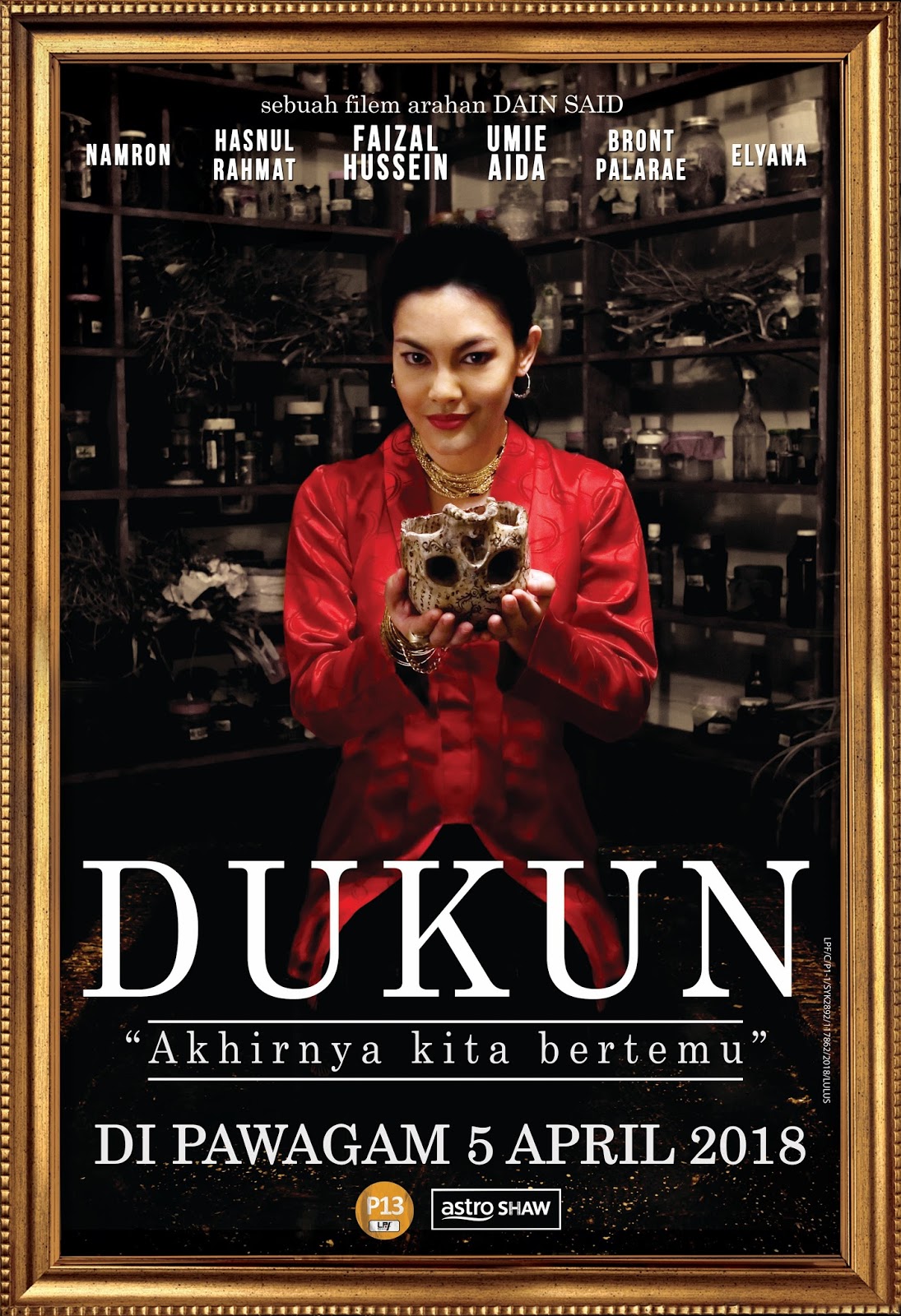

This also seems to be implicitly reflected of an internal absence of the spiritual as Mit has renounced Buddhism and seems suspicious of Islam. His daughter May (Jennis Oprasert) eventually calls in a Brahmin to exorcise the house, installing Buddhist shrines and other talismans as if overwriting the those of the local muslim community though this only causes more problems. Later, May consults a Buddhist priest but is told that he can’t help because the problem is on a different system though she’s also told something similar by other members of the community. Running underneath the conflict between Buddhist and Muslim culture is echo of a much older spirituality in the references to “black magic” and shamans.

What May learns is that this land has been cursed and counter cursed many times over, though they do perhaps manage to exorcise one particularly problematic spirit in literally digging up the past to learn the history of the house and that of the entities who seem to inhabit it but there are many other curses yet to be undone on this patch of scorched land that exists in a nexus between cultures, part of both and neither. What emerges is a kind of co-existence and a crossing of the streams as they must in the end marshal all of the spiritual powers to counter the danger presented by this extremely disgruntled spirit.

Panu Aree and Kong Rithdee conjure an atmosphere of intense eeriness rooted in a classic haunted house movie aided by the gothic environment of the Western-style home itself standing alone and isolated, not really part of a community yet not totally independent. What emerges is a kind of integration, the house as a machine with people inside it creating a home through diverse community and entrenched support systems that allow even the “weak-minded” Wit to shakes off some of his demons and begin to move forward with his life. Perhaps the key really is not to throw anything away, because everything belongs in the house and the house belongs to everything. Attempts at exclusion only invite fear and acrimony that cannot but eat away the foundations of a home built on cursed land.

The Cursed Land screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)