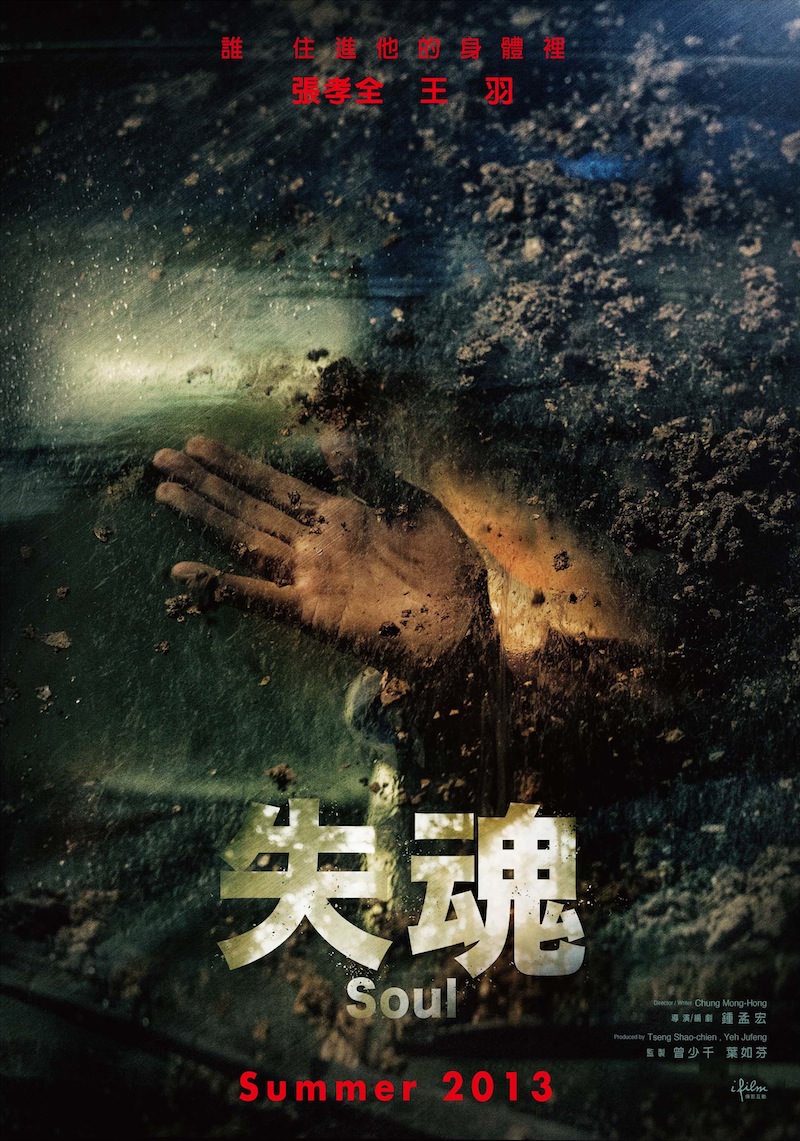

“Sometimes the things you see aren’t what they seem” the stoical father at the centre of Chung Mong-Hong’s supernatural psycho-drama Soul (失魂, Shī hún) later advises, for the moment creating a new, more convenient reality but also hinting at the mutability of memory and perception. Distinctly eerie and beautifully shot amidst the gothic atmosphere of the misty Taiwan mountain forests, Chung’s ethereal drama is at heart a tale of fathers and sons and the griefs and traumas which exist between them.

When sushi chef Ah-Chuan (Joseph Chang) collapses at work, no one can figure out what’s wrong with him, finally suggesting perhaps it may be depression. His boss instructs three of his colleagues to take him back to his apparently estranged family to recuperate for reasons perhaps not altogether altruistic. In a near catatonic state, Ah-chuan is barely present offering no response to his name and staring vacantly in no particular direction. When he finally does begin talking, it’s to insist he’s no longer Ah-Chuan explaining that this body happened to be vacant and so he’s moved in while Ah-Chuan will apparently be off wandering for some time. Ah-Chuan, however, then abruptly stabs his sister Yun (Chen Shiang-chyi), who had travelled from Taipei to look after him, to death and is discovered covered in blood sitting calmly over her body offering only the justification that she was intending to harm him.

Wang (Jimmy Wang), Ah-Chuan’s father barely reacts to finding his daughter’s corpse, merely rolling her under a bench and attempting to mop up the blood when a family friend, Wu (Chen Yu-hsun), who happens to be a policeman suddenly comes calling. Wang is either infinitely pragmatic instantly deciding there’s nothing he can do for his daughter so he’ll try his best to save his son, or else near sociopathic appearing to care nothing at all that Yun is dead. Nevertheless, realising that Ah-Chuan may be dangerous he takes him up to his remote cabin near the orchid garden and locks him inside while trying to figure out what or who this presence that has his son’s appearance might or might not be. As he later says, this brief time together is the most he’s spoken to his “son” if that’s who he is in years even if acknowledging that this Ah-Chuan is quite different from the old. Yet if it were not for the obvious fact that others see and interact with him we might wonder if Wang had simply conjured Ah-Chuan, projecting his own latent violence, guilt, and regret onto the figure of his son who is also in a way himself.

Yet whatever Ah-Chuan now is he finds himself growing closer to the old man, feeling a filial responsibility towards him that he otherwise would not own. He contacts a “messenger” from “across the woods” to help his find Ah-Chuan’s wandering soul to tell him that his dad’s not doing so well, entering a space of dream and memory that reveals the trauma at the heart of their relationship that might in part help explain Wang’s apparent coldness. Just as the two Ah-Chuans begin to blur into each other, so perhaps to father and son, Wang prepared to go to great lengths to protect his only remaining child while, ironically, offering some harsh words to his son-in-law for not better protecting “the only daughter I have”.

Chung hints at a kind fluidity of consciousness, each episode of “death” or “possession” accompanied by that of another creature, fish gasping and flapping around, a tired bug trying desperately to cling onto a leaf but failing, or a pair of snakes twisting themselves into a knot. Is Ah-Chuan merely experiencing a protracted dissociative episode under the delusion he is “possessed” while his essential selves “wander” the recesses of his consciousness or has someone else, a second soul, taken up residence in a body left vacant by a man who was in a way already “dead”. Wang in fact hints at this, telling the doctor that he had sometimes thought of Ah-Chuan as dead, or at least wondered if he might be seeing as they had long been estranged, suggesting that the Ah-Chuan of his heart and memory was already gone Wang believing himself to have killed something in him through his own violence when he was only a child.

The two men mirror each other, growing closer yet also further apart as they make their way back towards the truth that might set them, metaphorically at least, free. Often viscerally violent not least in its jagged, abrupt cuts to black that feel almost like dropping out of consciousness or else waking fitfully with brief flickers of other realities, Chung’s eerie, ethereal drama ventures into the metaphysical but in its strangely surreal final scenes returns us to a more concrete “reality” in which the way home is found it seems only in dreams.

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)