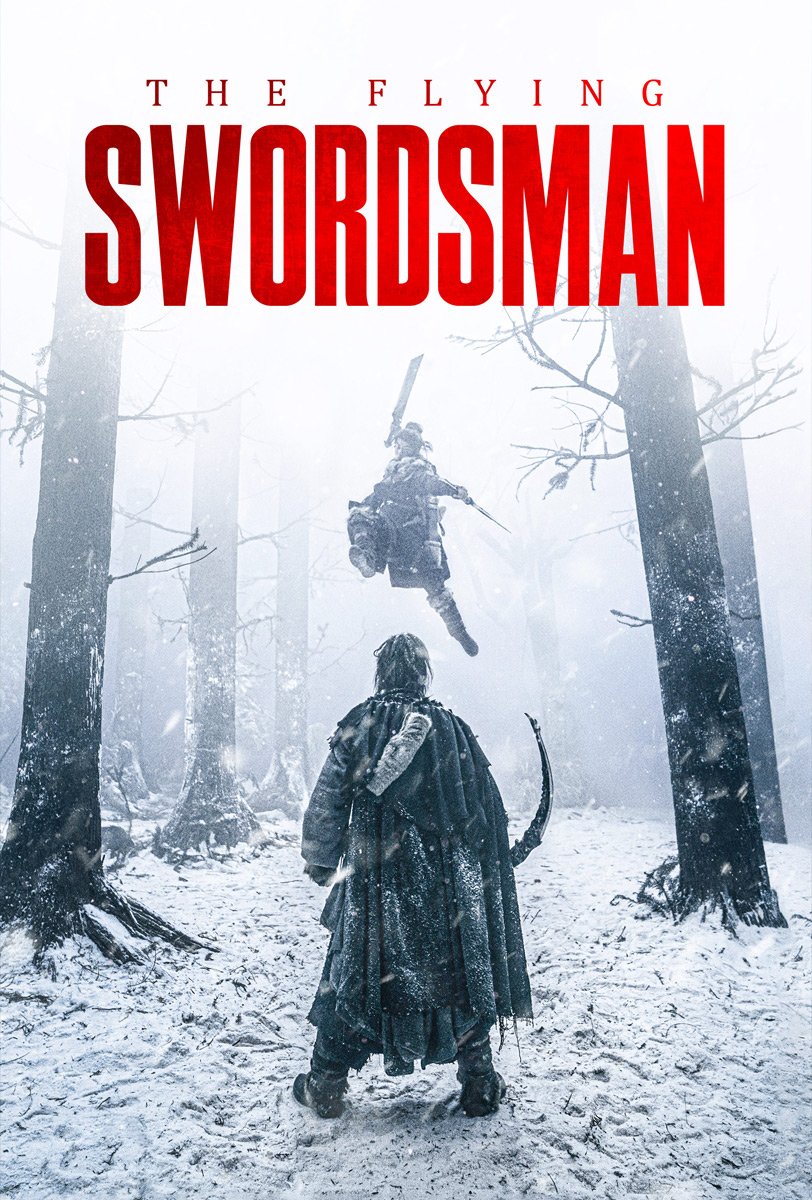

A disillusioned doctor quickly finds himself in over his head when he’s kidnapped by Chinese mercenaries in Michael Chiang’s oddly positioned action thriller, Wolf Pack (狼群, láng qún). Once again, the action takes place in a completely fictional Middle Eastern/Central Asian country with the mercenaries playing mysterious spy games in which their heartless amorality is at least heavily implied to be an affectation and that they are ultimately interested in “more than money” while covertly protecting Chinese interests abroad.

The film heavily implies that they are in fact in some way working for the Chinese authorities with a lengthy focus on the Chinese flag outside the place of government in this foreign nation given the unlikely name of Cooley (in fact, most of the names given for various people and places seem mildly inappropriate). The photograph sullen doctor Ke Tong (Aarif Rahman) carries around also features his father in a Chinese military uniform which might be why he is so reluctant to believe that he may also have been a member of this “private army” as his new boss Diao claims. Though Ke Tong is originally very hostile to Diao’s gang who have after all kidnapped him he later undergoes an entirely unexplained change of heart accepting that his father must have had his reasons for whatever he did so Diao is probably OK anyway.

In any case, their current mission involves defending Chinese energy interests against a local warlord who is working with European businessmen to disrupt a gas deal by placing faulty regulators designed to engineer an explosion which will apparently domino all the way back to the Mainland. Largely kept in the dark, Ke Tong is unable to see the big picture and keeps trying to help by doing righteous things such as shooting at a soldier hassling a young girl whose father he’d just killed but unwittingly making everything worse. Eventually he realises that the end client must be the Xingli group who are running the China-Cooley collaborative gas field, though even the energy official they’re later asked to protect seems to be prepared to die in order to ensure the project’s success and prevent a mass explosion.

Diao’s selflessness is also well signalled thanks to his tendency to listen to a recording of a baby crying and meditate on “all he’s lost” to be a mercenary which again reinforces the idea that they have a greater cause than simply money along with Diao’s position as a surrogate father not just to Ke Tong but to the other soldiers who are all, it is said, looking for a place to belong. The gang apparently also have some kind of role funding orphanages in China to prove that they aren’t just in it for the cash. Ke Tong too comes to feel a kind of brotherhood that makes the mission more than just mercenary activity and gives him an excuse to chase the evil war lord even though that is not part of their mission and really the villagers, including a small child who has been forced to do their bidding, are not their concern.

Despite starring two prominent martial arts stars, the film is much more focussed on technical wizardry and gunplay than it is on physical fights save for a late in the game confrontation between female mercenary Monstrosity and her opposing number as they try to liberate the gas field. Diao’s incredibly well equipped crew appear to be almost all-powerful, even if Ke Tong manages to play them at their own game, using fly-shaped drones to assist them in their work though the final mission involves an improbable plot device of the local government needing to sign a document by retinal scan within 60 seconds complete with an onscreen countdown via an encrypted briefcase computer in the middle of a firefight.

Chiang does indeed bring action with a series of high impact sequences one involving a large petrol tank explosion which results in several of the warlord’s men being engulfed in flames. It does however leave a thread of mystery hanging over Ke Tong’s quest to solve the riddle of his father’s death with the suggestion that not all of his body parts were collected hinting that there may be further conspiracies in store for a potential sequel though what seems clear is that Ke Tong has discovered his place to belong alongside a surrogate father figure doing quite questionable things but apparently working for the national good.

Wolf Pack is released on blu-ray in the US on 23rd January courtesy of Well Go USA.

International trailer (English subtitles)