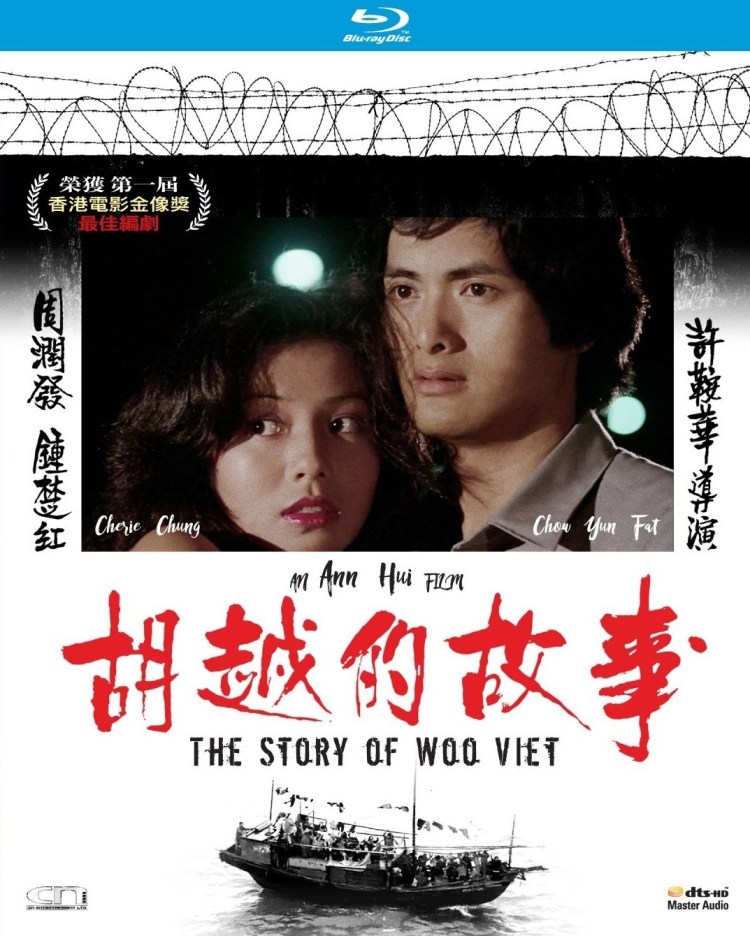

Displacement and a legacy of violence conspire against a young man attempting to escape the trauma of war in the second in Ann Hui’s “Vietnam trilogy”, The Story of Woo Viet (胡越的故事, AKA God of Killers). Starring a young Chow Yun-fat as Chinese-Vietnamese refugee headed to Hong Kong with a hope of making it to the US, Woo Viet’s story suggests that violence may be impossible to escape in a world increasingly corrupted by human indifference while only crushing disappointment awaits for those who live on dreams alone.

After years fighting for the South Vietnamese army, Woo Viet (Chow Yun-fat) is one of many young Chinese-Vietnamese men attempting to escape through claiming asylum in Hong Kong so that he can eventually apply for a visa to the US. The reasons he needed to leave are readily apparent. Even on the overcrowded, primitive boat on which he arrives in Hong Kong, Woo Viet has already witnessed several atrocities in which fellow passengers were dumped overboard, killed, or marooned on isolated islands. He has become the surrogate father to a little boy who is now alone on the boat because his dad was killed by the guards, and subsequently becomes a target for Viet Cong “special agents” after they strangle his friend in his sleep for having seen something he shouldn’t have.

Luckily, Woo Viet has a friend in Hong Kong, a female “penpal” Lap Quan (Cora Miao Chien-Jen) who sent him letters he rarely answered all through the war. After Woo Viet is forced to kill a special agent in the refugee camp in order to ensure his own survival, he finds himself relying on Lap Quan to help him organise a fake passport. He no longer has the luxury of waiting to do things properly, he needs to leave the country as soon as possible. The fake passports available are, for some reason, Japanese meaning he has to learn to at least sound plausible by picking up a few handy phrases to fool the border guards. It’s in the language classes that he meets fellow refugee Shum Ching (Cherie Chung Chor-hung) who is travelling to the US because a former customer who has already emigrated told her that he wanted her to come no matter what the cost. The problem is the HK trafficker has not been honest with either of them. Woo Viet may have a decent shot at actually making it to the US, but the girls are to be sold on at the first available Chinatown, which in this case is Manila where they’re waiting for a connecting flight. Having bonded with Shum Ching, Woo Viet surprises the traffickers by giving up his chance to go to America to stay in the Philippines to try and rescue her.

“Whichever Chinatown it is, I think my situation will be the same” Woo Viet writes back to Lap Quan, keeping up a correspondence which becomes increasingly dishonest as he struggles come to terms the shattering of all his dreams. Trapped in a Philippine Chinatown, he discovers the only way he can save Shum Ching is by serving the gangsters that “bought” her from the HK trafficker. Yet, also in his letter to Lap Quan he claims that “it is much simpler to kill people here compared to Vietnam”, while suggesting that the reason his situation is “the same” in Chinatowns the world over is that he has no real identity and can therefore “solve people’s problems with no problem” which is why he’s ended up working as a hired gun for HK gangster Chung.

Even so, he still harbours hopes of making it to the US when he’s made enough money to “redeem” Shum Ching who is already dreaming of finding a tiny house for them both where she can cook him proper Vietnamese food. While in Manila, he’s partnered with a slightly older man, Sarm (Lo Lieh), who came from Hong Kong a decade earlier. Woo Viet thinks he should have earned plenty of money after a decade making kills for Chung, so he doesn’t understand why he’s still here rather than off somewhere else enjoying a better life. He still doesn’t quite see that Sarm is a vision of his possible future, a man so beaten down by life that his only goal is to drink himself into an early grave. Sarm no longer believes in a future for himself, but he wants to believe in one for Woo Viet, and so he tries to help him but brotherhood, like love, is no match for the casual cruelty of the world in which they live.

Woo Viet’s floating rootlessness is perhaps an echo of a potential anxiety in a Hong Kong facing its own sense of displacement with the handover less than 20 years away, as perhaps are his feelings of hopelessness as he attempts to write himself into a better future in his now constant letters to Lap Quan in which he somewhat insensitively talks of his love for Shum Ching born precisely out of that same sense of rootless desperation. Soon after they meet, the pair attempt to visit a flower market at night but their romantic moment is disrupted by another refugee couple being caught and dragged away by police, instantly throwing a fatalistic shadow over their innocent connection. All Woo Viet wanted was an ordinary settled life, perhaps adopting that orphaned little boy from the refugee camp and bringing him with them as he and Shum Ching claim a better life in the US, but even small dreams are seemingly impossible in a world in which the predominating force is not love or compassion but violence.