Ettore Scola, one of the most celebrated filmmakers of Italian cinema in the late 20th century, returned to one of the country’s darkest moments for the film which is often regarded as his masterpiece – A Special Day (Una Giornata Particolare). Set on one particular day in 1938 when Mussolini rolled out the red carpet for his fascist brother in arms, Adolf Hitler, it focusses less on this “historic” meeting of “likeminded” leaders of state than it does on two small figures each lonely and excluded from the festivities for very different reasons.

Ettore Scola, one of the most celebrated filmmakers of Italian cinema in the late 20th century, returned to one of the country’s darkest moments for the film which is often regarded as his masterpiece – A Special Day (Una Giornata Particolare). Set on one particular day in 1938 when Mussolini rolled out the red carpet for his fascist brother in arms, Adolf Hitler, it focusses less on this “historic” meeting of “likeminded” leaders of state than it does on two small figures each lonely and excluded from the festivities for very different reasons.

The film begins with a lengthy sequence of archive footage of Mussolini welcoming Hitler and other major German politicians of the time to a series of festivities in Rome. Today, there is to be a large scale parade to demonstrate Italy’s military prowess before their new allies. Antonietta (a surprisingly dowdy Sophia Loren), wakes her entire family including her six children and boorish husband so that they may get ready to attend the parade like good little fascists. She herself will not be going (though she would like to) as housewives and mothers do not get days off and she simply has too much to do. However, her day is disrupted when her pet mynah bird (Rosamunda) escapes and lands on a balcony opposite. Now she notices the gentleman who lives across the way hasn’t gone to the parade either so she decides to ask him if she can try and coax the bird back in through his window.

The man, Gabriele (Marcello Mastroianni), is in something of a nervous mood. When we first see him he’s addressing a large number of envelopes whilst gazing mournfully at the photographs on his desk with half an eye on the pistol to his left. Somehow everything he does carries an air of finality, as if he’s tidying himself away, putting his affairs in order once and for all. Yet, Antonietta’s unexpected call reawakens something in him and suddenly he doesn’t want to be alone anymore. He tries to convince her to stay but she’s shy and slightly confused and, after all, she has so much to do, that she declines his offer and returns home only to feel a slight degree of regret and even resentment when she assumes he’s telephoned another woman right away. However, Gabriele pays a return visit on her and the two end up spending this very “special day” together.

A Special Day is about fascism and the fascist era in some senses, but in essence it’s about Antonietta and Gabriele – two lonely, lost souls each trapped in prisons to some degree of their own making but also those created by society. Antonietta is an ordinary middle-aged housewife. As a mother of six she’s more than fulfilled her societal role though she and her husband are thinking of another child as you get a special “big family bonus” with seven. Her husband is a high ranking fascist official and Antonietta herself is a big fan of Il Duce. Gabriele, by contrast, is an anti-fascist though perhaps more of a passive one. He had been part of the party for appearance’s sake but as we discover in passing fairly early on in the film, Gabriele is gay and an intellectual neither of which is particularly compatible with the fascist state.

Gabriele, played by Marcello Mastroianni brilliantly cast against type as the suave yet melancholy man out of place, has lost his job as a radio announcer precisely for the crimes of being gay and of being under committed to fascist principles. They fired him for not being a member of the party even though he was one because they said theirs was a party of “men”. The fascist credo says those who aren’t husbands, fathers and soldiers are not “real men” and Gabriele is none of these things. He also has a medical certificate which certifies him as not being a homosexual which is fairly counterproductive because, after all, who carries something like that around if they don’t have anything to prove in the first place.

Gabriele hates the fascist state most because it makes you deny what you are, to try to appear different to your authentic self so as to conform better to someone else’s ideals. Just as Gabriele’s identity has been erased by the desires of society at the time, so too has Antonietta’s though she is less well equipt to see it. She even has a scrapbook of fascist photos with slogans which proclaim that genius is something which only belongs to men and that a woman’s role is in the home, supporting her husband and raising his children. Effectively brainwashed, it had not previously occurred to Antonietta to question these ideas before but meeting Gabriele has planted the seed of doubt in her mind. She too has been forced to suppress her true nature and only now does she start to possess the courage to reassert herself.

Loren turns in virtuoso performance as an ordinary, aging housewife ashamed of the hole in her slippers and the ladder in her tights. Full of minor touches of brilliance such as her brief look into the mirror as if suddenly realising how old she’s become and starting to feel shy in front of this man she feels an obvious attraction to or her extended dreamy look towards the end of the film when suddenly surrounded by her family and finding herself mildly horrified by their fascist ideas, her performance in A Special Day must rank among her finest even in a career which is often marked by brilliance. Mastroianni, also cast against type, gives an equally accomplished performance as the quietly defiant Gabriele who knows what kind of fate awaits him and has already made his peace with the unfairness of his situation.

The film is cast in a heavy brown colour palate, almost sepia in tone, which gives it the feeling both of looking directly into history as if in a moving photograph and of emphasising the oppressive and rigidly restrictive society of the time. This is not a time for dreamers and outcasts, those who don’t readily conform to the fascist ideals will be ruthlessly discarded. However, through encountering each other and finding another weary, frustrated soul, something is reawakened in both of these isolated individuals. Here, there is hope for the first time. That if even two people can wake each other up enough to pierce this strange mass delusion then perhaps there might be a way out after all.

I actually had this queued up to post a little later but having just watched the film today I was slightly shocked to hear that director Ettore Scola has died at the age of 84 so I’ve moved it up a little to mark his passing. A Special Day is such a beautiful film that I could have written far more about it but it was running so long already.

A Special Day is available with English subtitles on Region A blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Unsubtitled scene from near the beginning of the film:

Of all the post-war Japanese filmmakers, the one who liked to twist the knife the most was surely Oshima. No subject too taboo, no pain too raw – he liked to find the sore spot and poke at it a little, if only in the hope of encouraging an accelerated healing, albeit one which would leave a scar to remind you that once you suffered. With Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (戦場のメリークリスマス, Senjou no Merry Christmas) he takes an unflinching look at the treatment of Japan’s prisoners of war and contrasts the Japanese forces with the different attitudes of the (mostly) British soldiers held within the walls of the camp.

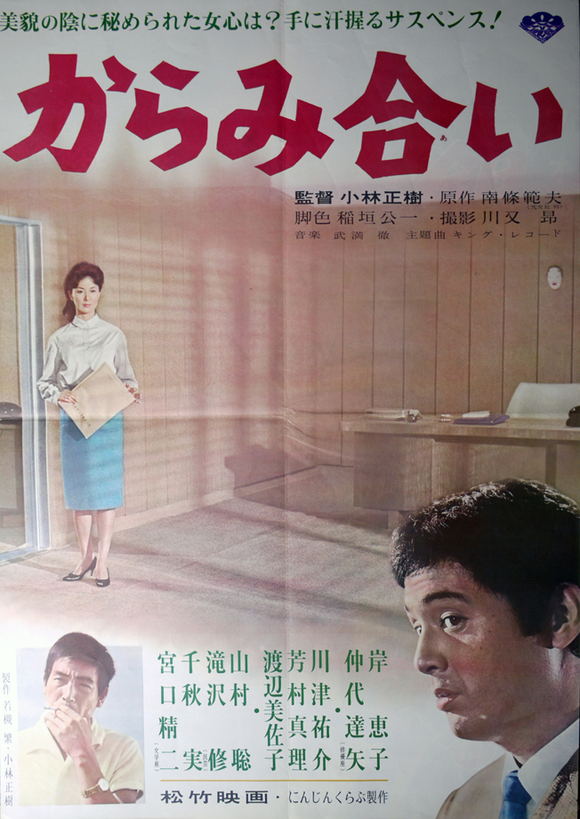

Of all the post-war Japanese filmmakers, the one who liked to twist the knife the most was surely Oshima. No subject too taboo, no pain too raw – he liked to find the sore spot and poke at it a little, if only in the hope of encouraging an accelerated healing, albeit one which would leave a scar to remind you that once you suffered. With Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (戦場のメリークリスマス, Senjou no Merry Christmas) he takes an unflinching look at the treatment of Japan’s prisoners of war and contrasts the Japanese forces with the different attitudes of the (mostly) British soldiers held within the walls of the camp. Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.

Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth. Masaki Kobayashi is still not enamoured with the new Japan by the time he comes to make Black River (黒い河, Kuroi Kawa) in 1957 which proves his most raw and cynical take on contemporary society to date. Set in a small, rundown backwater filled with the desperate and hopeless, Black River is a tale of ruined innocence, opportunistic fury and a nation losing its way.

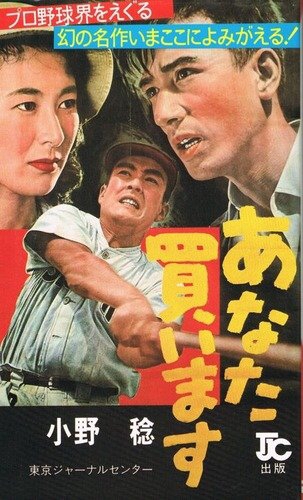

Masaki Kobayashi is still not enamoured with the new Japan by the time he comes to make Black River (黒い河, Kuroi Kawa) in 1957 which proves his most raw and cynical take on contemporary society to date. Set in a small, rundown backwater filled with the desperate and hopeless, Black River is a tale of ruined innocence, opportunistic fury and a nation losing its way. In I will Buy You (あなた買います, Anata Kaimasu, a provocative title if there ever was one), Kobayashi may have moved away from directly referencing the war but he’s still far from happy with the state of his nation. Taking what should be a light hearted topic of a much loved sport which is assumed to bring joy and happiness to a hard working nation, I Will Buy You exposes the veniality not only of the baseball industry but by implication the society as a whole.

In I will Buy You (あなた買います, Anata Kaimasu, a provocative title if there ever was one), Kobayashi may have moved away from directly referencing the war but he’s still far from happy with the state of his nation. Taking what should be a light hearted topic of a much loved sport which is assumed to bring joy and happiness to a hard working nation, I Will Buy You exposes the veniality not only of the baseball industry but by implication the society as a whole. There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.

There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.